Computers used to be vaunted thinking machines that helped scientists crack the secrets of physics or predict the weather.

Now, most of them just serve up emails or pictures of kittens.

That stark shift, however, has created the opportunity to rethink computer architecture and curb power consumption at the same time, says Andrew Feldman, CEO of SeaMicro.

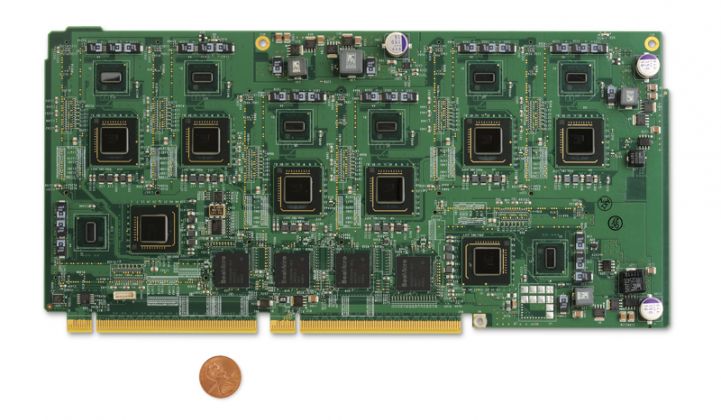

The SM10000-64, SeaMicro's new computer coming out today, consists of 256 independently functioning servers. Each server contains a dual-core processor, memory and a networking chip devised by SeaMicro. Each server, however, is only about the size of a credit card. Four of them fit on a single circuit board and 64 of those circuit boards fit into a case that measures about 2' x 2' x 2'. In all, the machine contains about the same amount of computing power as a full rack of standard servers, but consumes one-fourth of the power and one-fourth of the space. To keep power to a minimum, SeaMicro's processor of choice is Intel's Atom, originally designed for netbooks and web pads.

"Power and space are over 75 percent of your operating expense," he said. "We've removed 90 percent of the components."

The company's first system consisted of 512 single-core servers. The new version contains 256 dual-core servers so the computing performance is about the same. The new box, however, consumes around 15 percent to 17 percent less power than the previous version and both use fewer racks than traditional boxes.

Intel's latest Atom chips are also 64-bit processors, unlike the 32-bit Atoms used in the first server. That switch means that customers can adopt the new server without tweaking their applications. Customers include Skype, Mozilla, Oak Ridge National Labs, France Telecom and Rogers Communications. The sales cycle is around 90 days, he added. Customers play with an evaluation unit for about 30 days, run a pilot for around a week, and then order hardware. The customer list is crucial: server makers have come up with novel designs in the past and vanished without a trace. SeaMicro can at least point to the buyers it already has.

The SM1000-64 starts at around $149,000, but stock a data center with these and SeaMicro claims you'll save millions in operating costs.

SeaMicro's strategy essentially revolves around eliminating the waste and computing overkill in most data centers. Servers and the processors that go inside them have been largely designed for complex tasks -- Monte Carlo simulations, film rendering, etc. -- and thus they tend to value performance over efficiency. Unfortunately, most servers don't get used for those purposes. The vast majority serve up web pages. Servers also remain idle most of the time, but even in that mode they can consume 85 percent of the power they would normally consume. Virtualization has helped exploit computing cycles more efficiently, but data center owners only virtualize around 15 percent to 20 percent of their hardware. Generally, they maintain quite a bit of spare computing capacity to guard against traffic spikes. In other words, your data center churns through a lot of money and energy just being ready.

"Ten years ago, power wasn't an issue. Why is it now? There has been a change in the workloads," he said. "Now you have millions of users with ubiquitous access doing small, simple, independent workloads."

Swapping out Xeon chips for an Atom contributes to some of the power savings. "You don't want to take an 18-wheel truck to the grocery store," he said.

Nonetheless, the bulk of the savings, and the secret sauce inside SeaMicro's server, is the customized networking chip. The chips, when connected into the server rack, create a three-dimensional web connecting all of the processors. Rather than connect them in a point-to-point fashion, the networking chips are linked in redundant, torus-shaped loops. (A torus looks like a rubber band or those rings that make up Bib the Michelin Man.) Even if a link gets damaged or overburdened, the networking chips can reroute traffic. Ideally, computing performance can be maintained, and optimal paths for reducing energy or increasing performance can be determined dynamically. Optical communication networks operate on torus principles. IBM uses multidimensional torus-shaped networking in its BlueGene super computer. Prior to SeaMicro, CTO Gary Lauterback worked at AMD and Sun; both companies heavily exploited novel processor networking technologies for boosting performance.

"As you put them together, the shape emerges," he said. "It can scale up or down."

While the company has so far inserted Atom chips into its servers, it could insert more energy-efficient ARM processors. Several companies -- Marvell, Nvidia, Calxeda -- plan to produce ARM-based chips in the relatively near future. ARMs do not have the computing power that Intel chips have now, but they compute quite a bit less. And with large data centers facing escalating power bills and caps on their electricity consumption, a lot of these alternatives will have appeal.

Why not call it the Rack-In-the-Box or the DensePack Data Center? "I suck at names," Feldman said.