Part 2: It's the Meter That Matters

Every gas-powered car has a fuel gauge, and it doesn't take a degree in automotive engineering to understand that the faster the needle drops, the sooner you'll have to refill the tank.

Unfortunately, many of us are much less mindful of the energy we're consuming at home. And while the government has offered cash incentives for consumers to trade in their old gas-guzzlers, most Americans still live in houses that are real "clunkers" in terms of household energy efficiency.

As I stated in the introduction to this series, residential energy use in the United States accounts for roughly twice the greenhouse gas emissions produced by passenger cars, and more than one-fifth of our nation's overall carbon footprint. If we can cut household fuel consumption by 25 percent, we'll reduce our national carbon output by about 5 percent. That's equivalent to taking half of all existing passenger cars off of American roads, and saving as much energy as we now import annually from Saudi Arabian oil wells.

It sounds good on paper, but can we really achieve this goal?

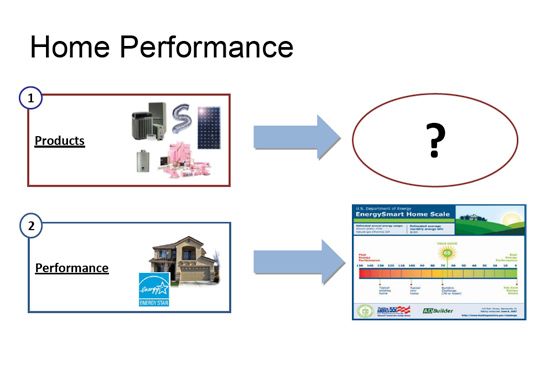

The good news is that there are plenty of effective products and technologies readily available to curb household energy waste, and American consumers have already been taking advantage of government incentives to install wall and attic insulation, double-pane windows, solar electric panels and high-efficiency HVAC equipment.

Unfortunately, the adoption rate for these measures has been much too slow to take a serious bite out of home energy use in America, and requiring all homeowners to invest in such costly renovations would be politically challenging and prohibitively expensive. So before we get out our collective checkbook to pay for a massive investment in state-of-the-art solar power systems or geothermal heat pumps, let's take a hard look at what really makes older homes burn through so much fuel.

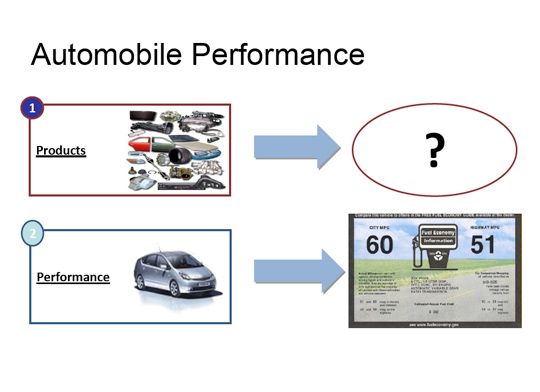

The most obvious culprits are the devices that actually consume energy – like furnaces, air conditioners, water heaters and household appliances. But in any home, net energy consumption is actually determined by a whole range of factors, and by the way various energy-related systems work together.

Let's say the furnace in your basement was made when F.D.R. was president and your winter heating bills are bleeding you dry. So you call in an HVAC specialist who recommends a slick new furnace that promises super efficiency through high technology. Hook that baby up to your leaky old ductwork in a home with poor insulation and air leaks, then run it at 72 degrees day and night all winter long, and I'm afraid you won't even be in the running for the "Greenest House on the Block" award.

The problem is, there's much more to your heating system than the furnace alone. The cost of heating your home is also profoundly impacted by three other crucial factors:

- The heat delivery system (air ducts or radiator pipes that distribute heat throughout the home)

- The building envelope (exterior walls, doors, windows, and those pesky drafts)

- How the occupants manage inside temperatures (a one-degree change at the thermostat can lead to as much as a 3 percent difference in how much energy the system uses)

What our hypothetical HVAC installer failed to mention is that these three factors tend to have a much greater effect on heating system performance than the efficiency rating of the furnace itself. In a typical American home, installing a high-efficiency furnace might cut energy use by 10 percent to 15 percent, while a reasonably affordable whole-house retrofit – including a well-sealed building envelope, improved ductwork and a smart thermostat to manage the system more effectively – can cut energy use by 30 percent to 50 percent, even if your old furnace isn't exactly dipping daintily into the power grid.

So as we look at ways to boost the efficiency of American homes, we must stop paying so much attention to high-tech gadgets and home improvement products and stay focused on the real task at hand – lowering our energy bills and reducing carbon emissions from home energy use.

In other words, it's the meter that matters.

Oddly enough, the rebates, tax credits and other incentives provided by governments and utility companies overwhelmingly favor high-cost solutions like solar electric panels, replacement windows and expensive heating and cooling products – instead of rewarding homeowners simply for drawing less energy through their gas and electric meters.

In my view, we as a nation urgently need to switch gears and move to performance-based home energy incentives that reward measurable reductions in household fossil fuel consumption, no matter how the homeowner achieves it.

If you want to see a great example of performance-based incentives at work, look no further than your neighborhood automobile showroom, where new cars are labeled with a federally mandated sticker showing estimated fuel efficiency in terms of miles per gallon. As fuel prices have risen, automakers have responded to consumer demand by developing hybrid power trains and other innovative ways to bring down their MPG ratings -- without any government agency telling them exactly how to make their vehicles more efficient. Measure and reward performance, and the market will innovate.

That's the kind of forward-thinking energy policy that will facilitate market-based transformation of the home energy retrofitting industry, and spur widespread adoption of cost-effective measures to make our household fuel gauges drop more slowly from "F" to "E."

To Be Continued in Part 3: A Road Paved With Good Intentions.

Matt Golden is President, Founder and Chief Building Scientist of Sustainable Spaces.

Image via Flickr/Creative Commons.