California could expand its grid markets to other states across the Western United States, and find a home for gigawatts' worth of solar and wind power that might otherwise be lost to curtailment. But it’s a tough political, economic and environmental balance to merge its green power goals with the brown power coming from states like Wyoming and Utah.

Even so, a coalition of environmentalists, Silicon Valley investors and green power companies is demanding that the California legislature take up the cause this year. In a Tuesday press conference, the group pointed to the news of possible multi-gigawatt solar curtailments this spring -- and the Trump administration’s attack on federal climate regulation -- as a spur to action.

“We’re seeing what I call a flashing light warning, with these increased curtailments,” Ralph Cavanagh, co-director of energy policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said in a Tuesday press conference. State grid operator CAISO said last month that it could need to curtail up to 8 gigawatts at a time of unneeded solar power onto the transmission system this spring, driven by “duck curve” imbalances between high solar generation and low energy demand.

Creating a regional grid market structure could let those excess gigawatts serve the needs of utilities hundreds or thousands of miles away, and create more than $1 billion annually by 2030 in lower energy costs for California, he said -- largely by finding an outlet for renewable energy that might otherwise be lost.

Tuesday’s press event marks the start of an advocacy effort to get California lawmakers to pass a law giving CAISO the authority to create an independent board, open to any Western utilities within the 38 separate “balancing authorities” west of the Rockies, Cavanagh said.

An independent board has been a key sticking point in negotiations between California and would-be partners, such as Rocky Mountain state utility PacifiCorp. The five-state utility, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, has said it won’t go forward with a shared balancing authority unless it’s led by a board with a governance structure independent of CAISO, and authorized to serve as a regional organization.

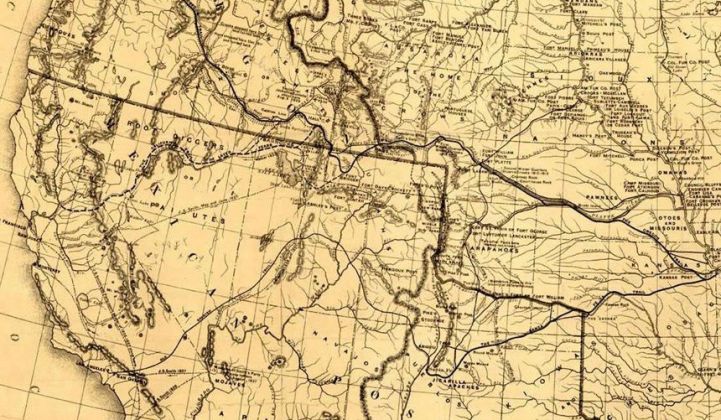

Today, these largely utility-run pockets of generation and transmission exchange energy through bilateral agreements -- a far less efficient way of aligning grid needs than the interstate transmission grid markets run by ISOs and RTOs in the Midwest and Eastern U.S. A CAISO report found that implementing a regional energy market with PacifiCorp alone could reduce power-related carbon emissions by about 12 million tons by 2030, and save California ratepayers up to $894 million, with some $691 million of that attributable to regional renewable procurement savings.

There’s certainly value to utilities in joining a regional grid that offers the opportunity to buy and sell energy based on day-ahead markets. At the same time, Cavanagh said, “It’s important to state that all Western states and California will retain their policy-making power. We’re not singling out anyone or excluding anyone. The more, the merrier.”

The idea of giving coal-heavy utilities like PacifiCorp a say in how a regional Western grid develops is worrisome to some. The Sierra Club has opposed the current plan on the grounds that it could allow coal-fired power plants to sell power and remain operational longer, adding to overall carbon emissions.

This confluence of conflicts led to California Gov. Jerry Brown postponing the interstate grid effort during last year’s legislative session. In recent months, Rocky Mountain states have been balking at the idea of giving California more control over their energy policies, the Salt Lake Tribune reported in January.

But NRDC's Cavanagh argued Tuesday that the benefits of opening markets to cheap and plentiful renewable energy outweigh the potential for extending the life of coal power plants. It's also an important way to help California achieve its renewable portfolio standard, which calls for 50 percent renewables by 2030, he said.

“We do have to have a broader market to expand here in California, and if we don’t have a broader market, it’s going to be very difficult to move it forward,” said Jan Smutny-Jones, CEO of the Independent Energy Producers Association, a trade association for power project developers representing about one-third of the state’s installed generation capacity.

A slow march from energy imbalance markets to regional balancing authority

CAISO is already operating some interstate energy markets. Since 2014, its Energy Imbalance Market, or EIM, has linked the state’s grid with a growing list of transmission utilities, starting with PacifiCorp and its grid covering much of Utah, Wyoming, southern Idaho and the California-Oregon border region, and expanding to Nevada utility NV Energy, Arizona Public Service, and Seattle City Light and Puget Sound Energy in Washington state. Portland General Electric and Idaho Power are slated to join in the next 12 months, and others are in discussions, CAISO spokesperson Steven Greenlee said in an interview last week.

But the EIM has its limits. Specifically, it allows participants to trade energy in 5-minute increments, to fill in for the “final few megawatts of power to satisfy demand within the hour it’s needed,” according to CAISO’s EIM website. That’s a relatively thin slice of the total energy balancing demands faced by the Western grid, and it requires a higher level of sophistication from the generators of demand-side resources that would bid into it.

Even so, EIM has helped California solar find a home, according to CAISO data that shows a spike in “avoided curtailments,” or power transfers at times when California has an excess of supply.

Day-ahead markets offer a far simpler way to schedule and forecast energy supply and demand, opening the field to a far broader set of participants. That’s important to the companies represented by Tim McRae, vice president of energy at the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, a public policy trade association with a membership roster representing one of every three private-sector jobs in the high-tech hotbed. “An integrated Western grid allows California to reach a broader market” and will “allow our wind and solar plants to operate at full capacity,” he said.

It’s unclear how the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle federal clean energy programs and policies might affect the regionalization push. CAISO is regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which has oversight over any plans to expand into a regional entity. Right now, FERC has only two commissioners seated, and there is potential for new appointees who might challenge the concept.

“That risk is there now, and it’s reinforced by the fact that the California Independent System Operator has the label 'California' on its back,” Cavanagh said. That’s an argument for regionalization, he added, since having more states and more utilities on board will help cushion CAISO from any interference based on hostility to the state’s green energy and carbon reduction efforts.

IEPA’s Smutny-Jones sees less threat of federal action derailing the regionalization process. “Opponents of expansion are raising this issue, but in terms of holding it back, there isn't any expansion of vulnerability to California seeking to expand its grid,” he said. “Other regional groups such as PJM on the East Coast and the Midcontinent ISO have states that have renewable energy portfolios and states that do not.”