Scientists say we must reach zero emissions by 2050 to avoid locking in dangerous levels of climate change, but while overall emissions have declined from power-sector decarbonization, stubbornly hard-to-reduce transportation and buildings emissions are still growing.

Even with aggressive electric vehicle and building electrification mandates, these two sectors are hard to decarbonize due to slow capital stock turnover — the process whereby old equipment, such as vehicles and appliances, is replaced with new equipment.

Capital stock turnover makes net-zero emissions harder to reach with every year we wait to start electrifying our vehicles and buildings. EV adoption is accelerating, and new all-electric homes are less expensive than mixed-fuel homes, but Americans won’t replace our several hundred million existing gasoline vehicles and fossil-fueled appliances for decades to come.

This creates significant lag time between setting all-electric sales targets and achieving the goal of all-electric fleets. And it only leaves a few opportunities to convert each vehicle or building, potentially locking in emissions at a level above the 2050 net-zero target.

While targets for a 100 percent clean-energy economy are important, policymakers must align their policy timelines and benchmark targets with the stubborn reality of capital stock turnover.

Only one or two opportunities for replacement

More than 60 countries including Germany and the U.K. have set net zero by 2050 goals. States and cities, along with corporations and utilities across the U.S., have also committed to net-zero emissions by 2050, and members of Congress are designing national climate legislation along the same net-zero pathway.

Power-sector decarbonization is laying a foundation to support economywide net-zero goals through transportation and building electrification, and America’s grid gets cleaner every day: Energy Information Administration data shows U.S. electricity was nearly 40 percent carbon-free in 2018. This trend must continue to ensure electrification is a viable pathway to cut transportation and building emissions.

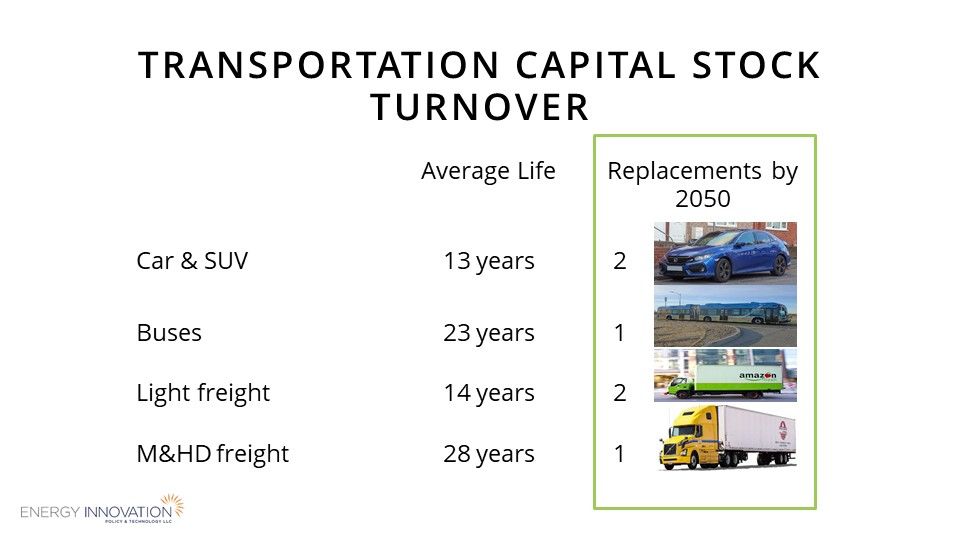

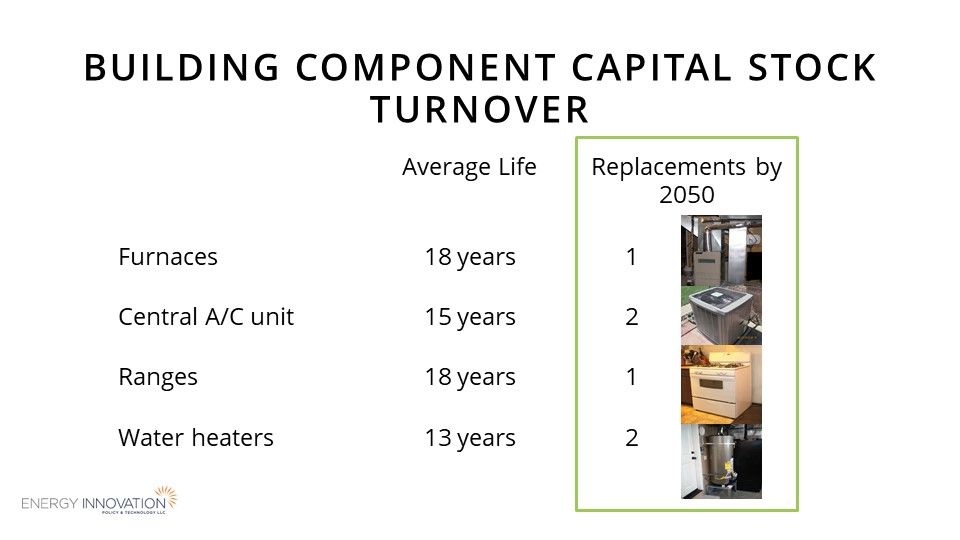

These net-zero commitments are imperative. But slow capital stock turnover means meeting these 30-year goals requires immediate acceleration of all-electric vehicle and building component market share as well as finding ways to accelerate the turnover process itself. Capital stock turnover and the average lifetime of vehicles and buildings (as well as building components) means we have one or two opportunities for clean replacement by 2050.

Zero-emission transportation by 2050

Transportation recently passed electricity generation as America’s largest source of greenhouse gases, responsible for 29 percent of total emissions. So how do we reach net-zero transportation emissions?

Decarbonizing on-road transportation through electrification (and to a much smaller extent, via the use of hydrogen or other zero-carbon fuels) is key for light-duty, bus and freight vehicles. Each vehicle must be replaced with a zero-emission version as it approaches the end of its life since we only have one or two replacement opportunities by 2050.

Lag time exists between 100 percent sales targets and full fleet turnover, approximately equal to the average equipment lifetime (23 years in the case of buses), meaning EV sales must accelerate rapidly to meet midcentury climate goals.

This same basic relationship between fleet composition exists for passenger, light freight, and medium- and heavy-duty freight vehicles.

Existing policies are already helping fleets convert from fossil fuels. California’s zero-emission vehicle mandate, now adopted in a dozen other states, requires a certain percentage of each automaker's sales to be EV sales. As a result, California EV sales account for approximately half of all U.S. EV sales, and all ZEV states combined account for approximately 60 percent of total U.S. EV sales.

But even this policy is insufficiently stringent to hit 2050 net-zero goals given the pace of capital stock turnover.

For example, by 2025 the ZEV mandate will likely require only about 8 percent of vehicle sales to be electric. What's more, its “banking” provision weakens the policy by allowing manufacturers to account for EV sales in future years if they’ve over-complied or by allowing manufacturers to trade those extra credits with other manufacturers. Similarly, its “pooling” provision allows ZEV states exceeding their goal to transfer extra credits to underperforming ZEV states (excluding California).

By comparison, California’s Innovative Clean Transit regulation aligns with capital stock turnover considerations by requiring full-transition to zero-emission buses by 2040 — an approach that is particularly important for other jurisdictions to adopt because we only have a median of one chance to replace buses between now and 2050.

California is currently considering an Advanced Clean Trucks policy similar to the ZEV mandate but geared toward light-, medium- and heavy-duty trucks. Unfortunately, the proposed sales targets aren’t aggressive enough considering the sales-to-fleet relationship: 11 percent sales from 2024-2030, with a 22 percent peak in 2030 of sales across all truck categories.

Governments can lead by example and accelerate transportation decarbonization by committing to convert their fleets as soon as possible to support mandates. Thankfully, some private fleets such as Amazon's are converting even in the absence of mandates, but policy requirements will be necessary to successfully electrify the transportation sector.

Zero-emission buildings by 2050

Direct fuel use in buildings is responsible for 12 percent of total U.S. emissions. Achieving net-zero building emissions by 2050 requires new buildings to be zero-emissions as soon as possible, but approximately two-thirds of the building area that exists today will still exist in 2050. So a heavy emphasis must be placed on decarbonizing existing buildings by replacing fossil-fueled appliances with electric ones.

Capital stock turnover for building components only offers one or two replacement opportunities by 2050, so governments must incentivize or require customers to replace all fossil-fuel-powered appliances with electric or zero-emission models beginning in the next decade.

An average gas-powered furnace lasts 18 years and will likely only be replaced once by 2050 if installed in a new building today. As such, it must be replaced (or originally installed) with a heat pump by 2030 at the latest. Most energy use in buildings goes to power space and water heating, so reducing total energy use in buildings helps meet climate goals by freeing up grid capacity for electrification while reducing customer bills.

As with transportation, governments can lead by example by converting their buildings as soon as possible. Cities are already banning gas in new buildings, favoring or requiring electrification over mixed-fuel builds, creating "feebates" to fund electrification projects and taxing heating oil.

States can accelerate building electrification through decarbonization goals containing interim targets, such as all-electric new construction by 2022. States also need to update building codes to require high-efficiency, all-electric new construction and retrofits, similar to city-level policies. State regulators must adopt a skeptical stance toward new natural-gas infrastructure, which is incompatible with the goal of zero-carbon buildings by 2050, and examine targeted electrification pathways that begin winding down gas infrastructure without sticking customers with undue stranded costs.

Infrastructure inertia cannot prevent opportunities to decarbonize transportation and buildings. As governments, utilities and businesses continue making flagship climate commitments, considering capital stock turnover can help ensure those commitments succeed.

***

Amanda Myers is a policy analyst at Energy Innovation, a policy research firm and consultancy.