Successfully developing renewable energy projects comes down to twelve core areas, according to a research group at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Public agency officials must understand the concepts "BEPTC" and "SROPTTC" to build the renewables they need to meet mandated goals.

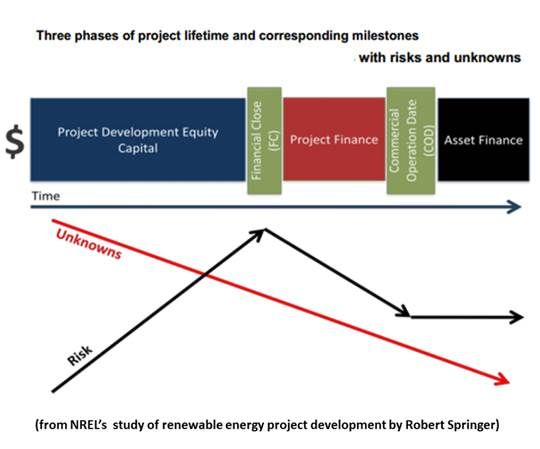

Project development is an entrepreneurial activity, explained the NREL Project Development and Finance Group’s Robert Springer in the report A Framework for Project Development in the Renewable Energy Sector. It entails risks and unknowns and requires time, money and other resources. Professional developers intuitively understand this.

But officials at the Departments of Defense, Energy and Interior, as well as state and municipal agencies and some utilities, have been charged by Bush and Obama administration executive orders to meet renewables targets, explained the NREL Group Manager Adam Warren. “And building a renewable energy project is different than building a new barracks.”

The NREL group set out to enhance understanding between officials seeking to meet renewables ambitions and the entrepreneurial developers they need.

The NREL group realized some of the earliest and most important lessons about managing a grid with a high penetration of renewables would come in Hawaii, where high power prices and expensive dependence on imported oil for electricity generation led to the Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative’s 40 percent renewables by 2030 mandate.

Springer and NREL Senior Project Leader Jeff Bedard were there to assist in a municipal water board’s wind project development, Bedard recalled, when an official told Springer the board would move ahead with development without having secured control of the proposed site through a long-term lease, such an essential it later became the "S" in the "SROPTTC" framework developed by the agency. Both realized immediately that a primer was necessary.

“A key tenet of early-stage development is fatal flaw analysis,” Springer wrote. “Fatal flaws absolutely need to be identified and analyzed quickly and accurately to avoid investment of scarce risk capital into ‘bad projects’ and to conserve these resources. This concept shapes the process of moving a development project forward.”

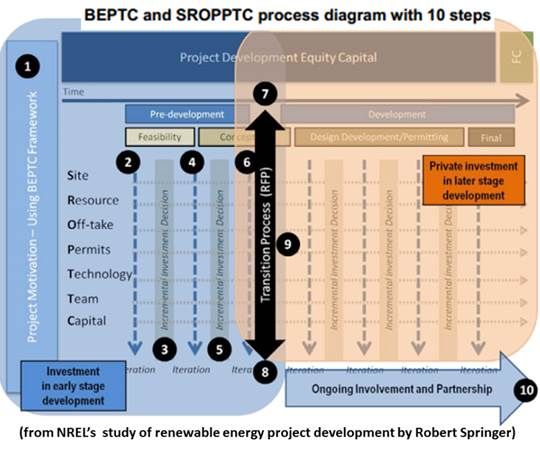

Springer, Bedard and the NREL team evolved “seven core subject areas” of renewable projects: site, resource, off-take, permits, technology, team, and capital -- or SROPTTC.

After presenting SROPTTC to officials, Bedard said, they realized there were a set of considerations that had to come first: baseline, economics, policy, technology, and consensus. That’s BEPTC.

These, Springer wrote in his detailed NREL paper, “are universal to the project development process and essential in successfully managing development risk.”

Site, resource, and off-take are most important, Warren said, because all the other pieces flow from them. You have to have the site and control of the site; you have to have an adequate resource that can win financing at a reasonable rate; and the off-taker has to be there.

“Of those, the off-take is most important,” Bedard added. And government agencies often don’t think that way. “Our role, in promoting government agency development, is showing them how important having a secure off-taker is from a business perspective, if you are using private money.”

But when the project is “a big, hairy, audacious goal, or a BHAG," Warren said, “Baseline, economics, policy and technology lead to the consensus among the stakeholders and decision-makers that has to exist if you are going to go forward.”

“These projects are changing the market,” Bedard explained. “You are up against the utility. You are changing the status quo. So you need consensus from a broad group of people to let that happen.”

The U.S. Virgin Islands had the BHAG of a 60 percent decrease in diesel reliance by 2025, Warren said, but they didn’t have any consensus on how to achieve it.

“The first work we did was the strategy, the mix of energy efficiency and renewables to get there. Once that was in place, we used the SROPTTC framework to identify solar and wind projects that could be built. Because it was a rigorous process that reduced risks for developers, they got bids from 27 quality solar developers, like SunEdison (NYSE:WFR), because the developers were confident the projects would get done. The result was power project agreements (PPAs) for 18 megawatts of solar, which represents 20 percent of their peak load.”

Warren and Bedard said the team continues to refine the primer and find ways to adjust it to different circumstances. “We are working on specificity,” Warren said. “The world is different for the DOD than it is for Interior than it is for a utility. Underneath the broad umbrella, we have to have a different set of tools for each.”

SROPTTC summarized:

- Site: A financeable physical location with full legal clarity regarding occupancy and physical constraints.

- Resource: Highly detailed hourly or sub-hourly data and analysis “of resource availability, quality, and characteristics within a tight range of certainty.”

- Offtake: “A critical milestone is securing the buyer of both the energy and the renewable energy credits (RECs) through a power purchase agreement (PPA) or other contracting method. In regulated markets, proper approvals must be in place. Issues of transmission and interconnection must be settled.

- Permits: All permits necessary. “If a project has a high hurdle for permitting, and therefore includes significant permit or policy risk, it needs to be understood and executed with that knowledge in mind.”

- Technology: This is the technology developed in the BEPTC framework, taken to the investment, engineering design, equipment selection, and procurement stages.

- Team: A team with proven experience and ability “in all business, technical, financial, legal, and operational aspects of a renewable energy project” is essential before “raising debt, equity, and incentive/grant program capital.”

- Capital: Meeting all other elements will attract the financial resources to get to the commercial operation date (COD). Financial closing is the last step but capital-raising takes place incrementally in the predevelopment and development stages as well.

BEPTC summarized:

- Baseline: Analysis of the energy supply reality and/or a clear statement of specific goals. Hawaii’s baseline was, “For energy and economic security, we can no longer rely on burning tankers of foreign-sourced petroleum on a month-to-month basis.”

- Economics: The total cost of acquiring energy from existing sources should be compared to the cost of acquiring it from the proposed renewable sources. “Relying on the project development process and/or a financing miracle to overcome the economics will rarely, if ever, result in success. As a rule of thumb, if a project does not have 20 percent to 30 percent of margin above general cost estimates to accommodate profit and uncertainty at the concept stage, it very well may not have supportive economics.”

- Policy: All federal, state and local policy requirements must be mitigated, removed or dealt with.

- Technology: Solar, wind or pick it. “It is necessary to defend against nonbankable or unrealistic early-stage technologies.”

- Consensus: “The project development process will involve many parties’ input, investment, and possibly compromise,” Springer wrote. Without consensus, “stakeholders can become adversaries to the project before it even begins.”