What does sustainability in the supply chain even look like? Well, depends on who you ask. But that is changing, according to a panel hosted by SAP in New York City on Tuesday.

Sustainability today is not about greenwashing for most corporations; instead, it’s about managing risk, according to Peter Graf, Executive Vice President and Chief Sustainability Officer for SAP. But whether the driver is compliance or corporate image, sustainability management is exploding. Not only do companies have to comply with government regulations, such as greenhouse gas emissions reporting mandated by the EPA or disclosing country of origin for wood products under the Lacey Act, but they also have to comply with the best practices established by other companies. If you want to do business with Walmart, you have to comply with any sustainability measurements that they have in place.

Furthermore, evidence is mounting that there is a strong business case to be made for making the switch. Sustainability practices in large companies can contribute to 38 percent higher profits, according to the National Environmental Education Foundation, and companies listed in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index consistently outperform the general market.

Following the supply chain, however, is still in its infancy. “The rules of the road aren’t there,” cautioned Jay Golden, Co-Founder of the Sustainability Consortium and Director of the Corporate Sustainability Initiative at Duke University.

But the road is being built. The Sustainability Consortium boasts some of the world’s largest companies as its members and is looking to build the methodologies necessary to truly measure sustainability. SAP is watching this evolution and also just released Carbon Impact OnDemand, the fifth version of its carbon software that now operates in the cloud and allows for full lifecycle analysis of products.

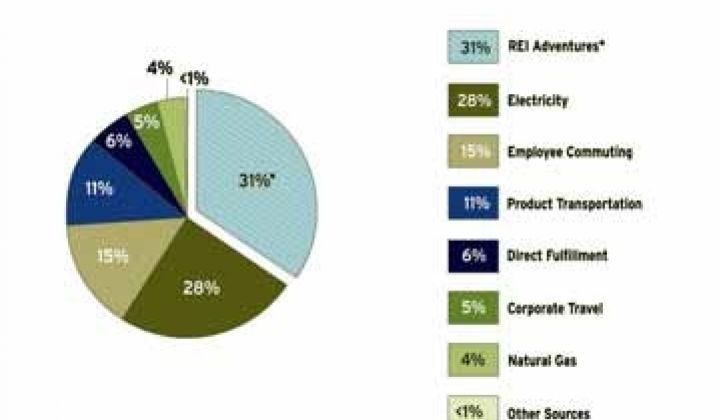

Even though there are reporting tools in place, such as software from giants such as Oracle and SAP, it’s not easy, according to Kevin Myette, Director of Product Integrity at Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI). Outdoor sporting companies have been far in front of many others on sustainability, but Myette admits that the language of sustainability is muddled. The biggest problem, however, is often getting everyone on board. “One of the biggest challenges in the supply chain is trust,” he said.

Myette said that even as the analytics come on board, there must be a parallel discussion among industries and within companies to define sustainability. Are you talking about water, carbon, social issues, or all of the above -- and beyond? The Outdoor Industry Association is trying to create some of those definitions and benchmarks for its own industry using an Eco Index, which assesses the lifecycle of products.

Trust is also a constraint within companies. “You would be shocked at the innovation when you just get a few people talking about the same thing,” said John Gagel, Manager of Sustainable Practices for Lexmark. He noted that engineers sometimes need the push to rethink a product, and that for Lexmark, bringing in engineers who deal with the end of life of a product to talk to the design team has been essential. “It’s screws versus snaps, plastic versus metallic,” he said. “Those conversations need to happen at the beginning of the design phase.”

Although the guidelines for getting down the supply chain and measuring it accurately are just coming out of the starting gate, the panel agreed it’s imperative to start digging deep. The result is cash savings, according to all of the panelists. Cutting carbon equals cost savings, and more importantly, risk reduction. “Sustainability is a mega-trend,” said Graf. “If you want to cover all of your risk, you have to go all the way down [the supply chain].”