The Section 201 solar trade case moved into the remedy phase this week as stakeholders filed recommendations on how to shore up the U.S. solar cell and module manufacturing business.

The proposals were submitted in response to the U.S. International Trade Commission’s determination last week that imported solar cells and modules have caused “injury” to U.S. producers of crystalline silicon photovoltaic (CSPV) products.

Pre-hearing briefs and statements on possible remedies were due by Wednesday, September 27 and made public on Thursday, ahead of a public hearing on October 3.

In their filings, trade case petitioners Suniva and SolarWorld urged commissioners to take swift and strong action to “stop the bleeding” and allow U.S. solar panel manufacturers to “grow and thrive.”

“The crisis caused by foreign market overcapacity now facing the U.S. CSPV cell and module industry is so extreme, the financial losses so great, that, to be effective, any remedy that is recommended to the president by the commission must be bold, extensive, and multifaceted,” wrote Suniva, which launched the Section 201 trade case in April.

With respect to proposed remedies, the financially troubled solar manufacturer recommended a tariff of 25 cents per watt on CSPV cells -- down from its initial 40 cents per watt request -- and 32 cents per watt on CSPV modules. A 32-cent per watt tariff on modules would bring prices in line with those that existed in late 2015.

According to Suniva, 32 cents is equivalent to 50 percent of the average unit value for solar modules during the case reference period of 2013 to 2015. A 50 percent ad valorem is the statutory threshold for a new tariff. However, as Suniva’s filing notes, module prices are likely to settle between 35 and 40 cents per watt once the hoarding prompted by the trade case ends. If that’s the case, the proposed tariff for modules would be closer to 100 percent of the present day unit value.

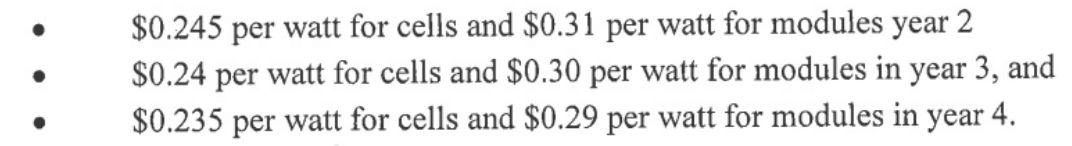

In order to attract new investment in the domestic manufacturing industry, Suniva also urged commissioners to recommend four-year tariffs on cells and modules. In accordance with the statute, the tariffs would ramp down over the four-year period.

Additionally, Suniva requested a floor price on all imported solar products of 74 cents per watt, down modestly from the 78 cents per watt in the initial petition. The proposed floor price would also decline over time.

Additionally, Suniva requested a floor price on all imported solar products of 74 cents per watt, down modestly from the 78 cents per watt in the initial petition. The proposed floor price would also decline over time.

Suniva’s co-petitioner SolarWorld made the same tariff request for cells and modules in its filing -- starting at 25 cents and 32 cents per watt, respectively. But rather than request a floor price, SolarWorld proposed an import quota starting at 0.22 gigawatts for cells and 5.7 gigawatts for modules.

Similar to Suniva’s proposal, the quotas become modestly less severe over the requested four-year remedy period.

Setting a minimum import price is unprecedented for this type of trade case and could cause a major setback for the broader U.S. solar industry, said Shayle Kann, senior vice president at GTM. In practice, though, quotas could have an equally damaging effect on U.S. solar industry players that rely on low-cost solar products to do business.

"I'm inclined to say the volume quote would be slightly preferable for the downstream industry to the minimum import price,” said Kann. “But it's still a very big tariff."

Petitioners presented the quota and the floor price options “to illustrate to the commission the necessity of having an effective remedy,” according to a Suniva statement.

Both companies said they believe an effective remedy must include two parts: either the requested tariff plus Suniva’s requested module floor price or the requested tariff plus SolarWorld’s requested quota.

Additional remedies: Buy American, tax credits, direct assistance

The remedy proposals don't end there.

Suniva's and SolarWorld's briefs go on to suggest additional efforts to shore up the few remaining U.S.-based solar cell and module manufacturers, including executive orders directing U.S. governmental agencies to adopt a “Buy American” policy for all solar cells and modules purchased by federal agencies.

The petitioners also proposed that the U.S. conduct a study of cyber, electrical grid and national security risks by using non-U.S. manufactured CSPV cells and modules; initiate bilateral and multilateral negotiations to reduce global excess capacity of cells and modules and restore a supply and demand balance in the global market; and consider the disbursement of funds to those seeking the development of new or additional manufacturing capacity relating to the CSPV cell/module supply chain.

SolarWorld went further to propose that the government to fully fund the Department of Energy’s SunShot program’s research grants for the duration of the tariff period. It also recommended amending the Investment Tax Credit program to keep the incentive at 30 percent in place from January 1, 2020 -- when the credit is slated to start ramping down -- for projects that use domestically produced cells and panels.

The idea of extending the ITC for U.S.-made products also appeared in a recent Greentech Media article by GTM Research analysts Shayle Kann and MJ Shiao entitled “6 Ways to Encourage American Solar Manufacturing Without Import Duties.” All in all, the petitioners cited three of the analysts' six recommendations.

However, SolarWorld’s brief does not include material from the GTM article that depicts the damage likely to befall the solar industry if the petitioners’ demands are met. In a scenario where the ITC approves a 78-cent floor price, GTM Research estimates that the remedies would eliminate nearly half of potential solar deployments over the four-year remedy term in exchange for limited new domestic module manufacturing.

Both Suniva and SolarWorld’s filings also reference a news story Greentech Media published before the injury finding that explored how foreign manufacturers were preparing to cope with the obstacle of tariffs, should they be imposed.

The article was submitted as evidence that trade remedies could increase foreign investment in U.S. manufacturing. However, the filings do not acknowledge reporting that explains why the limited timeline of the tariffs and capital investment needed to set up a factory make it highly unlikely that a manufacturer could profit from building a new U.S. plant before the remedy expires.

The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) underscored this point in its ITC filing this week. Global trade restrictions at the maximum level permitted would provide little benefit to the domestic solar cell and module manufacturing industry, the group argued, because tariffs that impose a greater cost on importers would logically push cell and module prices higher. Higher prices then hurt demand.

“[T]he adverse demand effects and limitation on domestic industry capacity will make it impossible for the industry to become profitable,” SEIA wrote. At the same time, downstream and service segments of the industry, as well as other solar parts manufacturers, would see significant harm.

As a result, SEIA said restrictive trade relief would fail two critical statutory requirements: 1) that any ITC trade remedies “effectively assist the domestic industry in adjusting to import competition,” and 2) that any remedy “cause greater economic and social benefits than costs.”

To accomplish these objectives, the best solution is to offer direct assistance to ailing domestic cell and module producers -- not to impose trade-restrictive measures, SEIA argued. Among other things, the trade group proposed offering up to $10 million per year to help the petitioners achieve scale and compete in all segments of the solar market.

How much tariff-free capacity is out there?

On timing, SolarWorld urged the ITC to deliver a remedy to the president ahead of the November 13 deadline in order to prevent further imports before the remedy takes effect. The surge in imports occurred in response to the threat of tariffs, as developers scramble to stockpile modules before a tariff artificially inflates the price.

“The build-up of even more inventories prior to the remedy date would render the proclaimed remedy ineffectual,” the brief states.

Based on currently available manufacturing data, GTM Research counts total tariff-free capacity of 4.7 gigawatts, including U.S.-made cells and modules, available thin film, and imports from free trade partners not covered by the tariffs.

Factoring in SolarWorld’s proposed import quotas, the U.S. market would access a total of 10.6 gigawatts of potential solar capacity for 2018. GTM Research predicts an 11.1-gigawatt market for that year, meaning a slight shortfall in product compared to demand.

Volume alone doesn’t tell the full story though, because in order for these modules to get installed there has to be someone willing to buy them. Projects that would have penciled out under the previous market won’t after prices go up, and simply having access to a certain volume of modules won’t change that.

Additionally, Suniva and SolarWorld are teetering on the precipice; there’s no guarantee that they can ramp their factories to full production capacity in a timely manner. Neither company has submitted an adjustment plan to explain how trade remedies will enable them to get ahead of the foreign competition.

If they do pull that off, and successfully reboot their manufacturing facilities, the next concern will be bankability -- do buyers trust or want their product? The testimony against the two at the ITC included damning accounts from several high-profile former customers.

In many ways, the Section 201 trade case is about to get more complicated “as the ITC shifts from a data-driven injury phase to a more economic-theory and policy-driven remedy phase,” according to Morten Lund, partner at Stoel Rives practicing in the Energy Development group.

“Yet to come are the hard decisions about whether the domestic producer industry can return to a competitive position, what measures can best facilitate that transition, and the timing and content of such measures,” he wrote in a post this week.

This week’s filings are just recommendations. The ITC will take them into consideration, but will also conduct its own analysis and could arrive somewhere else entirely. Those conclusions will be sent to the president by November 13. Ultimately, the final remedy decisions rest with President Trump, who has yet to take a public position on the case.