Much ink has been spilled over Spain's recent renewable energy boom-and-bust cycle. In response to generous tariffs and loose oversight, developers in Spain installed over 2,600 megawatts of solar PV capacity in 2008, or roughly 50 percent of global installations that year.

This rapid market growth overwhelmed policymakers and prompted a drastic policy change, including a 500-megawatt annual cap on future installations and a new auction mechanism to award future contracts. Since the bust, many have cited the Spanish experience as a cautionary tale for policymakers worldwide, an example of how not to finance renewable energy.

In response, the government has passed a number of highly contested measures to rein in solar costs, including retroactive changes to existing solar contracts.

Spain’s decision to move ahead with retroactive cuts has stirred up a storm of protests from the solar industry and from investors worldwide, and a wave of lawsuits is already in the works to counter the government’s plans. (Editor's note: We at Greentech Media are gearing up for a debate between Travis Bradford an Barry Cinnamon on feed-in tariffs at our Solar Summit taking place March 14 and 15 in Palm Springs. It promises to be a spirited discussion)

Many inside and outside the industry are now saying, “It didn’t have to be this way.”

Indeed.

This briefing attempts to shed some light on Spain’s renewable energy woes, and to help both analysts and investors understand the underlying causes behind the recent flurry of retroactive cuts that are jeopardizing Spain’s solar industry.

Spain’s Electricity System

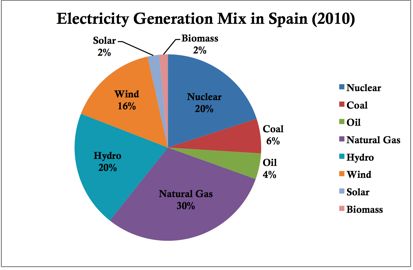

Spain has a highly diverse electricity system, including a wide spectrum of different technologies and a significant percentage of renewables (see Figure 1).

Utilities operating in Spain are required by law to purchase electricity from renewable energy projects on a priority basis. This applies to all generation categorized in what is called Spain’s “Special Regime,” which includes almost all renewable energy installations in the country, with the exception of large hydro.

The Special Regime includes a set of fixed prices offered to renewable energy technologies, as well as a premium option that offers a bonus on top of the prevailing electricity price. Like many other feed-in tariffs around the world, these standard prices were designed to increase investor certainty, and help Spain leverage private capital to meet its national Renewable Energy objectives.

Figure 1

Source: IDAE 2010

The conventional wisdom has it that Spain finances its renewable energy development through taxes, and that when solar development boomed in 2008, politicians backpedaled, fearing that it would prove too costly to the Treasury.

While this story is sensible, it is inaccurate: Spain does not finance its renewable energy industry through taxes. Its private utilities finance it with debt (which is scarcely better).

El Deficit

While the generation side of Spain’s electricity market is largely deregulated, certain elements of the market remain regulated, such as retail electricity rates.

The government effectively limits how much electricity rates for homeowners and industry can rise in any given year.

What this means in practice is that when electricity generation costs increase, utilities are unable to recover all of their costs, creating a shortfall. Since the prices offered to certain renewable energy technologies such as solar PV are much higher than retail rates, this creates a gap between what utilities pay to procure electricity, and what they can charge their customers.

It is this long-standing rate regulation that gives rise to Spain’s electricity system deficit.

To be fair, this shortfall has been a problem for the Spanish electricity system for decades, well before renewable energy entered the picture in a significant way.

For instance, when natural gas prices in Spain spiked in 2006 to 2007, the increase in gas-fired generation costs was responsible for the largest share of the deficit. Much like with solar PV today, utilities were unable to recover their costs by raising rates, as they otherwise would have in the absence of such regulation.

As solar PV has grown in market share, it has become responsible for a growing share of the total annual deficit, compounding what was already arguably an unsustainable situation.

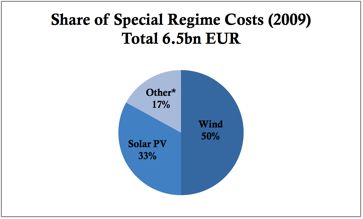

The total costs associated with Spain’s Special Regime in 2009 were approximately 6.5 billion EUR ($8.5 billion USD). This reflects the costs associated with purchasing electricity from renewable energy projects; each technology contributed to this amount differently (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Source: CNE 2009

* includes biomass, biogas, solar thermal, and small hydro.

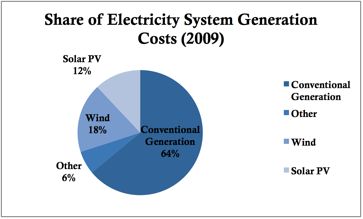

As pointed out above, solar PV generation costs exceeded what utilities could charge by the largest amount, making it the largest proportional contributor to the deficit: while it supplied roughly 2 percent of total electricity to the grid in 2009, it was responsible for approximately 12 percent of total electricity system costs in that year (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Source: CNE 2009

Note: Conventional generation here includes coal, oil, nuclear, natural gas and large hydro.

No se puede

In 2009, utilities recovered roughly 22 billion EUR from electricity sales. However, the total costs of generation, including both conventional and renewable energy, topped 26 billion EUR, resulting in an annual deficit of over 4 billion EUR. This sum was then added to the total system debt, which is now over 20 billion EUR.

When this problem began to get worse in 2005, the long-term strategy devised to deal with the deficit was that utilities would be allowed to gradually recover it through incremental rate increases between 2005 and 2020. In the short term, utilities would package the majority of the debt (just over 5 billion EUR at the time) into securities and sell them on the capital markets.

Since 2005, this is largely what utilities have been doing -- issuing just over 5 billion EUR per year in securitized debt. This has helped keep their books sound for a while, but much like using a line of credit to pay a credit card, the deeper issue remained unresolved. Both utilities and the government acknowledged that this situation was highly problematic.

Enter credit crisis, stage right

When the global financial crisis hit, Spain’s major utilities were no longer able to find buyers for their securitized debt, and utilities became concerned that the growing burden would negatively impact their credit ratings. Without buyers for that debt, the annual shortfall effectively shows up as an empty cash flow line item in utilities’ balance sheets.

Making matters worse, the crisis caused borrowing costs to spiral upward, making the situation even more uncomfortable both for utilities and for the government. Utilities turned to the government to address the issue either by providing government guarantees on the securities, or by allowing rates to increase more rapidly to eliminate the deficit altogether. While the crisis effectively forced the government to do the former, it made it politically impossible to do the latter.

As the crisis wore on, Spain’s ballooning electricity system deficit became increasingly unmanageable, fueling a lot of uncertainty in the renewable energy market and placing enormous pressure on the government to address the underlying issue.

In response, the government has tabled a number of disruptive and highly controversial proposals, including retroactively modifying existing solar PV contracts. As highlighted at the outset, talk of retroactively modifying contracts has provoked a furor of opposition from both investors and solar industry representatives worldwide.

Adelante?

In 2009, the government created a national “Securitization Fund,” the structure of which was further elaborated in 2010. A new charge of 0.50 EUR/MWh will be levied on all generators for the use of transmission and distribution lines. The securitization fund provides rights to a portion of these grid access charges, which will be allocated to fund the deficit.

In addition, the government has agreed to guarantee the securities issued by Spanish utilities, effectively assuming liability for over 20B EUR in debt. It began auctioning off the government-backed securities in January of this year, reducing significant pressure from the utilities concerned.

Legislation signed into law in 2010 has also introduced fundamental changes to the payment terms offered to existing solar projects. This new law (RD-L 14/2010) imposes caps on the total number of hours per year for which existing solar PV projects are eligible to receive feed-in tariffs (see Table 1).

Table 1:

|

Solar PV Installation Type |

Number of Total Annual Hours Eligible for the Feed-in Tariff |

|

Fixed Installation (i.e., no tracker)

|

1250 |

|

Installation with 1-axis

|

1644 |

|

Installation with 2-axes

|

1707 |

What is particularly damaging about these measures is that they fundamentally alter the financial assumptions on which existing solar projects were built. Previously, no limits were placed on the number of eligible hours, and projects had an incentive to maximize their output. These cuts are scheduled to apply until December 31, 2013, after which a new schedule will take effect, with different provisions for projects in different regions. The government expects to save 4.3B EUR from these initial changes

Spain has also introduced a number of other measures, including scrapping the premium payment option for wind and solar thermal (CSP) systems over 50MW, and cutting tariffs for future solar projects by 5%-45%, depending on project size.

Further ideas to finance the deficit have also included a windfall tax on nuclear or hydroelectricity generators, as well as the introduction of a gasoline tax, though neither of these has yet been implemented.

Supporters of this rather ad hoc medley of responses claim that they demonstrate the government’s resolve to address the deficit plaguing its electricity system.

Critics claim that it pulls the rug out from under billions of dollars of capital investment, making Spain a blacklisted country for countless foreign investors, including private equity firms and pension funds, both of which are increasingly attracted to the infrastructure sector. They argue that these retroactive changes severely undermine the credibility of Spain’s regulatory regime, and will jeopardize the ability of other regulated industries such as water and natural gas to raise capital as well.

On a positive note, the European Commission has recently condemned Spain’s actions, stating that it believes that it risks undermining the case for foreign investment throughout the European Union.

The billion-dollar question now is whether Spain’s politicians will backpedal yet again. With court cases on the horizon, it is far from clear what the final outcome will be, but one thing that is beyond doubt is that the reputation damage is done.

What Spain's experience since 2008 demonstrates is that while policies like feed-in tariffs can fuel a rapid scale-up in renewable energy technologies, they can all-too-easily exceed policymakers' expectations if proper adjustments and oversight mechanisms are not in place.

If there is one thing to be learned from Spain’s odyssey, it’s that policy design matters: like Spanish explorers feared centuries ago, going too far can send one’s ship straight over a cliff.

***

Toby D. Couture is Energy & Financial Markets Analyst with E3 Analytics, based in London, U.K.