SolarCity has an idea for how to help California utilities tap their own customers as an integral part of their billion-dollar distribution grid plans: put them first in line.

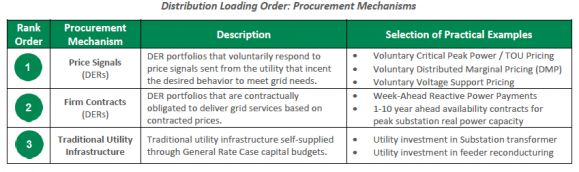

The plan is called a “distribution loading order” -- a variation of the state’s longstanding loading order that puts renewables and efficiency ahead of fossil-fuel-fired power for large-scale power procurements and transmission planning.

In a white paper this week, SolarCity wrote that the structure could be a key lever for customer-owned distributed energy resources (DERs) to compete for billions of dollars of distribution grid projects being planned by the state’s big three utilities.

In simple terms, a distribution loading order would require utilities to assess green-powered, grid-responsive customers and their aggregated value first, before paying for new wires, poles and transformer upgrades. It would also put existing DERs in front of utility contracts and procurements for distributed energy, like Southern California Edison’s groundbreaking Local Capacity Requirement contracts last year.

“Our idea is to start with what’s there, and send the signals on what to do,” said Ryan Hanley, SolarCity’s senior director of grid engineering solutions, in an interview. “After you find out what you can do with your pricing signals, then you do an RFP.”

It’s a simple concept, but with radical implications for how utilities identify, plan and procure for their distribution grid needs. It also comes at a time when California is suddenly wide open to innovative grid-DER integration concepts.

Under a California Public Utilities Commission decision last year, the state’s big investor-owned utilities are already turning in distribution resource plans (DRPs). These lay out where their grid circuits could be helped or hurt by distributed energy resources, and set goals for figuring out just how they can best be valued as grid assets.

But last week’s integrated demand-side resource proposed decision from Commissioner Mike Florio takes the DRP process to the next level, authorizing new markets, programs or tariff structures that can actually start paying DERs for that value -- or, in fairness, withhold payment if they’re going to be a grid burden.

Florio’s proposal calls for policies that allow rooftop solar, energy storage, plug-in vehicles, energy efficiency, demand response, and any other kind of demand-side resource to compare its costs and benefits to any other, in any combination, without being trapped by programs or incentive structures for single technologies.

California is rife with projects of this sort, but they’re either pilot-scale, as with PG&E’s distributed demand-response programs, or they're being conducted under closely-held utility terms, as with Southern California Edison’s LCR contracts. Meanwhile, customer incentives are split up into energy-efficiency programs, self-generation incentive program credits, energy storage mandates, demand response payments, and the potential to play a role in the state’s grid markets.

In this kind of fractured and overlapping economic landscape, customers don’t have much chance of banding together to compete on utility contracts, and utilities have limited visibility into the range of value those customers could provide, said Stephanie Wang, senior policy and regulatory attorney for the Center for Sustainable Energy.

“Existing incentives and value streams don’t provide the right signals to adopt complementary solutions that provide synergistic value to the grid,” she said. That goes for how California’s greenhouse-gas reduction goals align with various programs as well, she noted.

A distribution loading order could force utilities to go out and identify these values, if only to find out if they’re less costly opportunities than third-party procurements. And, if it’s expressed in the form of new tariffs that actively reward DERs for meeting “right place, right time” grid solutions, it could bring that value out of the landscape, by giving companies and customers the financial incentive to invest in them.

Building the flexibility of customer choice into grid planning

One of the challenges in making customers a part of grid planning is that it's difficult to know what they’re going to do. Energy prices are a blunt instrument when it comes to forcing behavior change. Even automated and aggregated DERs lack the always-on communications and control between grid operators and, say, utility-scale solar and wind farms.

Still, there are methods to determine the effective load-carrying capacity of distributed renewables at scale, or predict the response of lots of household batteries and smart thermostats to rising and falling prices.

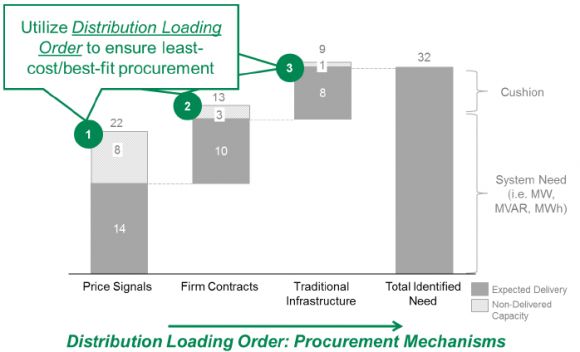

SolarCity proposes building some headroom into how the distribution loading order calculates the capacity of customer-owned DER, versus its “availability” for those must-have grid moments, “to probabilistically discount the different types of distribution products." That would inform the utility as to how much it needed to contract for, or build itself, to stand in as last-resort grid resources, as the following chart shows.

As for how companies like SolarCity will go about proving their DERs can do what they say they can, “Smart inverters will be on every new installation going forward,” Hanley said, which will allow monitoring and control of solar, storage and EV chargers at homes and businesses.

California’s utilities have made it pretty clear that they want to have direct access to whatever DERs they take on as grid investments, whether to actively dispatch them for grid needs or to monitor them for compliance with their chosen task. At the same time, they’re starting to experiment with tariffs for behind-the-meter batteries, smart thermostats and plug-in EVs to help defer distribution grid investments

Ted Ko, policy director at behind-the-meter battery startup Stem, noted at a Thursday CPUC workshop that his company is installing 85 megawatts of storage under its Southern California Edison contract, and is meeting some stringent terms for its ability to work closely with the utility on how they’re dispatched. At the same time, “Price signals are going to get all these customers who have these assets engaged at a very low cost," he said.

That’s one way to shift the risks of picking the wrong technology from utility ratepayers to the private sector, said Tom Starrs, SunPower’s vice president of market strategy and policy, at Thursday’s meeting.

“There is an opportunity to encourage customers themselves to invest in the assets. That kind of takes care of the problem of stranded regulatory costs,” he said. While individual customers might make unwise investment decisions, “You won’t have ratepayers as a whole bearing the burden of that.”

Of course, because utilities earn a regulated rate of return on capital expenditures like distribution system upgrades, that’s not necessarily something they’re happy about. SolarCity CTO Peter Rive suggested at Thursday’s meeting that utilities be allowed to earn returns on distributed energy resources as a service. “You could meet that load growth with standalone solar. In other cases, it could be solar with a little battery. In either case, it’s much cheaper than a transformer upgrade.”

In other words, Hanley said, “We think we can run a business off of that.” SolarCity is already selling Tesla’s behind-the-meter batteries with its solar systems and has been testing their ability to work in concert as an aggregated grid resource. But “if there were time-of-use tariffs, we could put in batteries every day, and use them to shift load,” he said.

Connected water heaters and smart thermostats could be added too, said Hanley. “You could be like us, and do it all for customers, or if you’re a hardware provider, you can supply the technology to adapt to these prices. It’s great for Nest too -- they can control their thermostats and adjust as needed.”