Lance Weislak, the Director of International Finance at Chevron Energy Solutions, gave a talk last week at SVLG's Energy and Sustainability Summit on "Financing Clean Energy and Green Infrastructure."

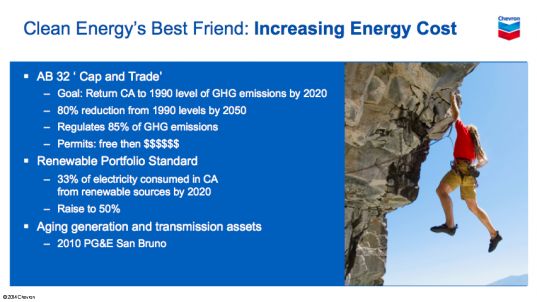

Especially relevant in these days of rising oil prices, Weislak said that clean energy's "best friend is increasing energy cost."

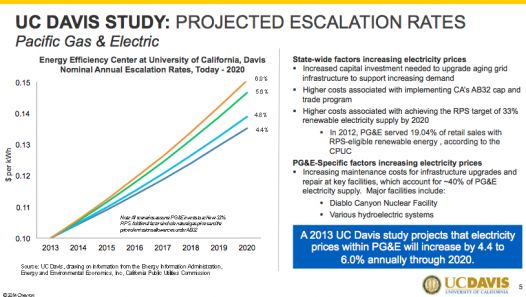

The price of electricity is going nowhere but up. The Chevron exec cited California's Diablo Canyon nuclear plant and the 2023 expiry of its license as an accelerator of electricity prices. A Chevron-commissioned UC-Davis study shows electricity prices rising 4 percent to 6 percent per year. He said that Los Angeles Department of Water and Power rates will see 8 percent increases.

"It makes the decision to go renewable that much easier," said Weislak.

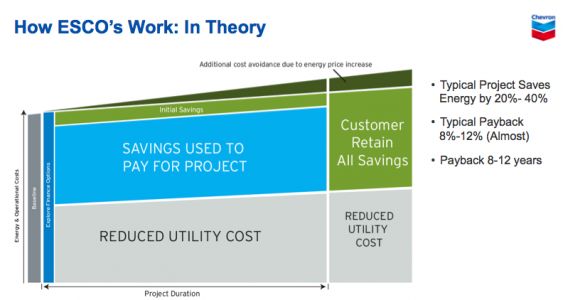

Chevron Energy Services is an energy service company (ESCO) and calls its projects "shared savings contracts." In "every project we do, we perform an energy audit," he said. Chevron learns how the customer spends money on electricity and then focuses on the low-hanging fruit.

He said that a typical project will save 20 percent to 40 percent with "zero capital cost out of pocket."

Weislak preached the four commandments of ESCOs and energy efficiency:

- Thou shalt turn lights off when not in the room (behavioral change)

- Thou shalt optimize and run efficiently what you have (retro-commissioning)

- Thou shalt maximize "negawatts" before megawatts

- Thou shalt use renewables for remaining energy needs

The Chevron exec suggested the following "loading order" for financing an energy efficiency project:

- Grants (Department of Energy, CEC, foundations)

- Rebates and utility incentives

- Low-cost financing (e.g., 0 percent CEC Loan)

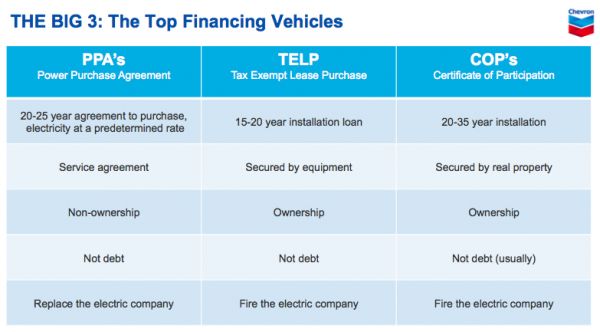

- Third-party financing (e.g., tax-exempt lease purchase)

He also had some things to say about "The Big 3" financing vehicles: power purchase agreements, tax-exempt lease purchases, and Certificates of Participation.

Chevron Energy Services focuses on the public sector because while "cities don't go out of business," they still face enormous funding pressures. While the private sector wants a 20 percent return and a fast payback, the public sector is comfortable with 10 percent to 12 percent payback.

A project with the City of Livermore, California cost $12.5 million but required no money down to finance 6,203 streetlights and 1.4 megawatts of solar on twenty-one buildings, for a first-year savings of $765,231.

Weislak claims that "government gets it right" with Public Code 4217, which allows sole sourcing on an ESCO project "so long as the savings are greater than the cost." He said that 19 percent of California electricity goes to water use, but water savings don’t count under 4217.

His "big idea" is to count water savings in savings calculations. He sees Chevron as being able to identify, develop, finance, and implement water savings in the public sector and create what he terms a "WESCO," (water savings company).

Matt Arnold, managing director of sustainable finance for JPMorgan Chase, sees the virtue in the Livermore project but notes that it is "just a single" in the grand scheme of things when "we need home runs." Arnold's critique of ESCOs is that they tend to focus on the short term and will accept very little emerging technology risk. He also noted that "big retrofits have long paybacks" and are "really difficult to squeeze into a project."

Since 1990, U.S. ESCOs have grown the market from less than $500 million to more than $5 billion in 2011. And according to a new analysis of the market from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (PDF), revenues will double or even triple from $6.4 billion in 2013 to between $13.3 billion and $15.3 billion by the end of the decade.