Silverado Power believes its approach to development can avoid the controversies impeding the advance of renewables in Southern California.

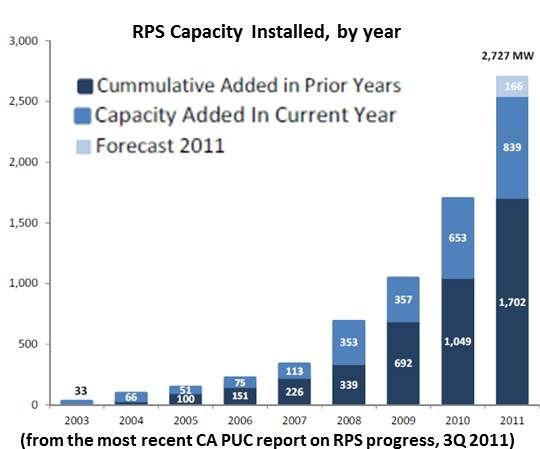

In response to those controversies, major renewable energy projects got some not-so-great news from Los Angeles County’s Board of Supervisors in the last week of January. The Supervisors’ decisions threaten California Governor Jerry Brown’s ambition to obtain 33 percent of the state’s power from renewables by 2020.

NextEra Energy’s 200-megawatt Blue Sky wind project and Element Power’s 250-megawatt solar-wind hybrid project were both denied permits for meteorological towers by the Supervisors. Without the data that can be gleaned from those towers, those projects will not be able to obtain financing.

Developers are flocking to L.A. County’s Antelope Valley because of enormous wind and solar resources there and the sizable transmission system being developed by Southern California Edison (SCE). When complete, SCE’s lines will deliver thousands of megawatts of electricity generated by Antelope Valley’s wind and sun to California’s populous urban centers.

The controversies center on the ambiguous term 'mitigation.' It was originally associated with the impacts associated with the development of renewables. If harms could not be avoided, they might be mitigated by preserving adjacent portions of land for habitat, preservation and recreation.

More recently, 'mitigation' has come to also mean something like compensation to the communities being impacted by the projects. Neighbors of large projects contend that upheavals from construction and the interruptions of life as it was before development require this second kind of mitigation.

Silverado Power has a different approach, with which it hopes to minimize the need for both kinds of mitigation by being in touch with the community early and identifying the right sites.

Silverado was founded in 2010 by former executives of Recurrent Energy and Renewable Ventures. It is backed by Portugal’s Martifer Solar, which has recently been installing solar at the rate of 100 megawatts a year, according to Silverado Manager of Business Development Chris Wiedemann.

Silverado Power has 16,000 acres of land under site control and approximately three gigawatts of interconnection positions allotted to it across the U.S., largely in the Southwest. It has been granted 355 megawatts of use permits in the region and expects to soon have some 500 megawatts more.

Antelope Valley was one of the company’s first targets, Wiedemann said. But the company was aware of the mitigation controversies swirling around Antelope Valley Solar Ranch One, the 230-megawatt photovoltaic undertaking First Solar bought from NextLight in 2009 and is now building for Exelon, which it sold to last year.

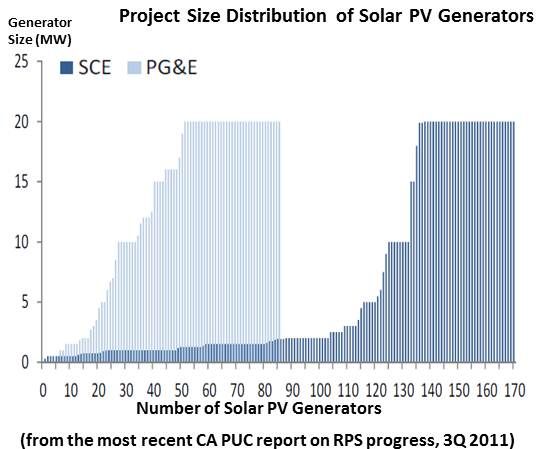

Drawing on the experience of “other players in the community who have had varying response to community outreach,” Wiedemann said, Silverado chose to aim for smaller, lower-profile projects. “Our focus in that region is between five and 20 megawatts” and is “interconnection-driven,” he continued.

That approach, Wiedemann noted, reduces the need for mitigation of the first variety through the selection of land “that has been previously disturbed: retired farm grounds or properties that are being actively dry-farmed or grazed.” This avoids “major mitigation hurdles” and “major backlash” from community groups, Wiedemann explained, and “takes the controversial issues out of the picture.”

An indication of the soundness of Silverado’s strategy, Wiedemann said, is that that company was "awarded 100 megawatts of PPAs [power purchase agreements] from SCE in the 2010 bidding for under-20-megawatt projects.”

Initially, Silverado has narrowed its focus to three L.A. County projects, Central Antelope Dry Ranch (52 megawatts), Lancaster WAD (5 megawatts) and Silver Sun Greenworks (20 megawatts).

They have received three conditional use permits (CUPs) from the City of Lancaster and one from the City of Palmdale, Wiedemann said. But those cities welcome renewables developers. The prickly and passionate stewards of L.A. County’s high desert are another matter.

“One of the biggest hurdles facing these projects right now is permitting,” Wiedemann said. “We’re putting a lot of time and energy into the L.A. County approval process” and “working very closely with County planners” so as to move ahead with development and the “jobs and investment” it will mean for the region.

As to the second type of mitigation, Wiedemann said, “Our approach has been to get out there early, meet with these groups, present the projects, address concerns in the earlier stages of development and not do an eleventh-hour outreach approach. We see ourselves as long-term community members and participants, and the only way to validate that is to get in front of these folks early and listen to the feedback.” Silverado, he added, has been in contact with “a majority of the town councils in the region.”

Demonstrating the challenge developers face in the Antelope Valley, a local Town Council member’s comment on the vigorous Silverado outreach was, “You better tell them to get their asses over here.”

Wiedemann is nevertheless cautiously optimistic. “Our hope is to maintain a strong relationship with the local groups and interests,” he said. “What we hope will not happen is being [viewed as] guilty by association with some of these other projects that are sited in less optimal areas. That’s the larger risk. Our process and our siting strategy will hopefully prevail: Smaller projects, lower profile and siting away from sensitive biological and cultural resources and local landmarks.”

Silverado, Wiedemann said, intends to be “a long-term partner in these communities, not a fly-by-night developer that comes and goes.”