Price declines in residential solar and battery systems like Tesla’s Powerwall mean solar-plus-battery systems will soon be found in homes and businesses at the grid’s edge around the country. But what role will utilities play in the fast-approaching storage shift?

While energy efficiency, demand response, and solar are still cheapest, storage prices have fallen 80 percent in five years, meaning utilities may soon have to consider batteries as an equal grid resource.

Like other distributed energy resources (DERs), customer-owned distributed storage puts competitive pressure on utilities by reducing customers’ grid reliance. As DER costs continue falling, customers can increasingly afford to rely less and less on the grid for electricity.

Storage in the context of load defection

This phenomenon, coined “load defection” by the Rocky Mountain Institute, is antithetical to traditional utility business models where increased electricity sales drive revenue growth. Some load defection is not necessarily a bad thing, as long as it does not progress to full grid disconnection.

Ideally, electricity system operators would be indifferent as to which types of resources meet system needs and policy goals, be they distributed, centralized, or traditional grid infrastructure.

Distributed and centralized resources should compete to serve customers. Storage should be deployed at the locations and scales that maximize its overall system value. This kind of system optimization necessitates a certain degree of load defection -- or at least load evolution.

But a future in which large numbers of customers disconnect from the grid entirely would be much worse than these kinds of changes to load dynamics, and it would be a raw deal for both utilities and consumers. A collection of uncoordinated pockets would eliminate the resource-sharing benefits, resulting in an unnecessarily expensive and inequitable electricity system.

Avoiding this future is in the long-term interests of system operators and distribution utilities. To support optimized deployment of distributed energy resources, including storage, incumbent utilities should consider owning and operating some distributed resources (Australian utilities are already moving in this direction).

On the one hand, utility ownership could facilitate an even bigger market for DER technologies in the most valuable locations, sharing benefits among all customers. But on the other hand, utility ownership could undermine competition and innovation.

The role of battery storage

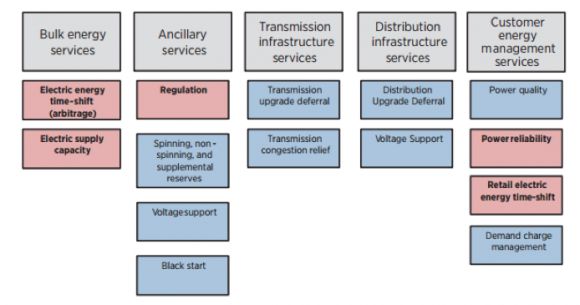

Unlike other DER technologies, distributed battery storage is extremely versatile, functioning as generation, distribution infrastructure, load and demand response all at once. Some of those functions (like distribution infrastructure) clearly fall under the distribution utility’s “natural monopoly” franchise, while many other services have long been successfully subjected to competition without adverse effects. This versatility of storage makes the propriety of utility ownership a murky question.

Battery storage is still expensive, and system operators are quite capable of providing needed grid flexibility with cheaper resources (e.g., demand response) and distribution upgrades. But as the grid gets cleaner and more modern, the value of flexibility will increase, increasing the potential value of energy storage. Assuming markets are structured to pay for the full range of flexibility services, battery storage will begin to compete in many more applications.

FIGURE 1: Services Provided by Battery Storage

Source: IRENA Battery Storage for Renewables: Market Status and Technology Outlook 2015

In the absence of a real-time distribution level market, distribution utilities are well positioned to identify high-value locations and times for certain services across the full fleet of resources. Customers (and DER aggregators) respond to the rate structure, and will act to optimize the system only when properly compensated. Under common rate structures, customers are more likely to operate storage and maximize on-site benefits, rather than optimize the grid.

Moreover, unpredictable customer-sited storage may even require distribution system upgrades, like rooftop solar has in some high-penetration areas. By contrast, distribution utilities with knowledge of the scale, timing and location of energy, ancillary service and future capacity needs could maximize the short- and long-term value of distributed storage through operational changes and rate reform.

Pros of utility-owned storage

Utilities can integrate storage into long-term system-wide planning, determining the most valuable way to operate storage in real time alongside other resources. If utilities were allowed to own storage as costs continue falling, they would gain a versatile new tool to help optimize the distribution system, increasing flexibility and enabling other cost-effective customer-sited resources.

Because utilities evaluate all resources to determine the lowest-cost way to maintain reliability, they are positioned to take advantage of storage’s ability to act like generation, transmission, load or demand response, depending on what’s most valuable at the time.

Distributed battery storage operation and installation also benefits from economies of scale, meaning system costs may drop with larger or simultaneous projects. But more importantly, utility-owned and operated storage could operate in concert with other distribution infrastructure or other storage units -- imagine fleets of utility-owned distributed storage deployed and operated as an integrated part of the distribution infrastructure portfolio.

As a result, utility-owned storage may be the cheapest option to meet system needs if opened up to a competitive bidding process.

Finally, utility ownership of distributed storage could support access for low-income customers who otherwise lack the finances to buy a distributed storage unit, enabling them to access the grid-wide benefits of storage through the utility.

Cons of utility-owned storage

Utility ownership of distributed storage does raise market power concerns and could stifle storage innovation and deployment in three main ways.

- The utility may use ratepayer funds to install storage in one area, diluting the grid value of customer-sited storage investments in that area and crediting customers less as a result.

- Distribution utilities have direct access to customers and branding advantages over third-party installers, presenting barriers to entry and innovation for private companies while raising the possibility of market manipulation to prevent competition.

- Utilities have a theoretical ability to use storage as a distribution system optimization tool, but may be otherwise motivated since system optimization of this kind is not necessarily rewarded under traditional cost-of-service regulation. In fact, under most models, utilities have financial incentives for larger investments as long as they meet “used and useful” prudency tests -- in other words, higher capital expenditures drive higher profits under the traditional regulatory model.

Considering storage is still relatively expensive, it has a high bar to meet before becoming the resource of choice for utilities. On the other hand, customers have direct incentives to save on energy bills, and innovative customers and energy management companies could optimize the use of storage from the grid’s perspective if given the right rate structure. Many recent innovations in electricity service have been driven by companies eager to compete with incumbent utilities.

Case in point: New York’s vision of utility ownership of distributed storage

New regulatory models can capture the pros of utility ownership while limiting the cons. New York’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) includes rules to limit utility market power while still incentivizing optimal distributed storage deployment.

The REV is fundamentally changing the utility business model by requiring utilities to create and operate a DER market or “platform.” This market development may drive system optimization by making utilities neutral about which resources provide grid services, optimizing distributed asset performance, and animating markets for customer-sited resources.

In the first order adopted under REV, New York’s Public Service Commission disallowed utilities from owning behind-the-meter distributed energy resources, stating market power concerns outweigh most benefits of utility ownership and citing three issues: conflict with the REV’s purpose of animating private investment (supported by proven interest from third-party installers); branding advantages and the appearance of impropriety for incumbent utilities; and conflicts with new utility platform management functions.

However, the REV does acknowledge the unique potential for storage, allowing utilities to own and operate distributed storage under limited conditions.

New York’s regulators allowed some value dilution for customer-sited storage in exchange for more optimally located distributed storage. By prohibiting utility ownership of customer-sited storage, though, regulators ensured the utility will not compete with innovative third parties looking to install and operate individual customer storage systems. These changes in New York are accompanied by performance-based regulation, to incentivize optimal choices for distribution system resource deployment.

Recommendations for policymakers

Regulators should consider four policy options to incentivize utilities to use cost-effective deployment of distributed storage to reduce system load factor, avoid distribution upgrades, improve power quality and offer options for low-income customers.

- Refine rate structures to incentivize optimal deployment of customer-sited storage and move toward more finely calibrated rates that reward grid services for energy-aware customers. Customers will respond to electricity rate design when making choices about whether to invest in storage. Time-invariant rates do not reward customers for providing flexibility services, but opt-in rates aligned with modern, dynamic grid systems (like time-varying rates) empower energy-aware customers and third-party aggregators to maximize the value of storage, provide grid services, and stay connected.

- Use pilot programs to let utilities experiment with incentivizing and operating distributed storage in the most valuable locations on the grid. Utilities should own storage for demonstration and assessment of the full range of technology possibilities, and can set up incentive programs for customers to install and own storage with a default to (override-able) utility operation (e.g., Southern California Edison’s storage procurement filing from 2014). More experimentation can lead to a better understanding of how to optimally deploy storage.

- Encourage utilities to share aggregated data about distribution system locations where storage would be most valuable. One advantage utilities bring to storage deployment is their unique knowledge of system needs. With access to better information (sufficiently aggregated to protect privacy), companies can better compete to fill system needs, reducing the need for utility investment.

- Break the link between volumetric sales and utility profits; ensuring the utility is indifferent to investing in distributed, centralized, or grid infrastructure as long as demand for grid services are met at least cost and policy goals are achieved.

The calculus may be different for other distributed energy resources like rooftop solar, but battery storage presents a unique set of concerns for utility regulators.

Utility ownership with smart constraints can unlock storage’s potential, offer new revenue streams to utilities and third parties, and protect against market power concerns. New regulatory models will be required to strike the right balance, ensuring customers remain connected and the utility “death spiral” never materializes.

***

Michael O’Boyle and Sonia Aggarwal represent America’s Power Plan.