With residential solar financing companies leading the charge in rooftop solar installations around the country and utility companies starting to invest big money in that business, it’s worth asking a seemingly simple question. Why haven’t retail utilities, which sell power directly to customers in deregulated markets, cut out the middleman and started selling rooftop solar leases and PPAs themselves?

The answer is pretty complicated, but can be boiled down to two main reasons for and against the idea. On the “for” side, retail utilities would love to add low-cost rooftop solar to their array of competitive offers to acquire and retain customers. That could also give them a way to hedge their bulk power purchases, by giving customers a generation resource that’s producing the most power around the same time that grid demand and pricing peaks.

But they’re certainly not going to do it if it ends up losing them money -- and just how to draw the line between making and losing money on a rooftop solar deal can be pretty hard for retail electricity providers, or REPs. That may be why we haven’t heard a lot out of REPs like Constellation Energy that have launched their own residential rooftop solar business lines, and why we’ve seen a much more go-slow approach from others, like NRG Energy, that are only starting to emerge.

Beyond the challenge of building a new business from scratch to compete with upstart, yet growing, contenders like SolarCity, Sunrun, Sungevity, Vivint and many others, REPs have a much different set of economic calculations to contend with. First, every solar-generated electron a customer consumes equals an electron they don’t buy from the REP, making the way they configure that long-time payback from each customer a critical calculation.

Second, while REPs don't directly bear the burden of covering the fixed costs of maintaining the grid that keeps solar-equipped customers supplied with power when the sun doesn’t shine, they do indirectly pay those costs through agreements with the “wires” utilities that serve that purpose. Without some way to prove that their solar customers are reducing that power “traffic,” at the right times, they’ve got no way to reduce those costs.

That’s where smart meters can end up playing a critical role, according to research firm DNV KEMA Energy & Sustainability (now part of DNV GL). In simple terms, old-fashioned meters that are read every month have no way to record the hourly contribution of rooftop solar power to that reduction in power pulled through the grid. But smart meters, which record power consumption on an hourly or fifteen-minute basis, can -- and that provides a record that can be turned around to make a money-losing solar installation into a profitable one.

These points are laid out in a November presentation, using data from New Jersey, Connecticut and Massachusetts, three states that combine competitive energy markets, lucrative solar incentives and net metering programs, and a significant portion of smart-metered customers.

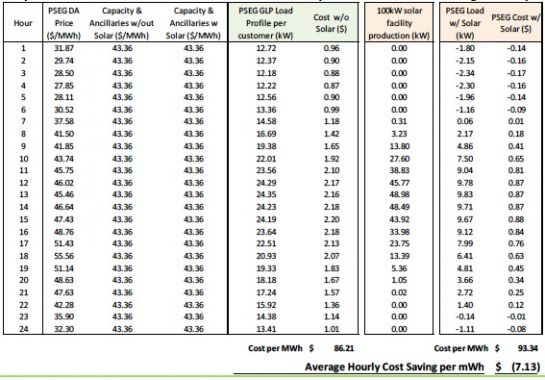

“The smart meters are key to this, because the real-time information is crucial,” Soner Kanlier, vice president at DNV KEMA Retail Energy Markets, told me in a November interview. Here are two charts, based on data from New Jersey utility PSE&G that illustrate that point. The first shows that costs actually increase for a retailer serving a solar-equipped customer with a monthly meter:

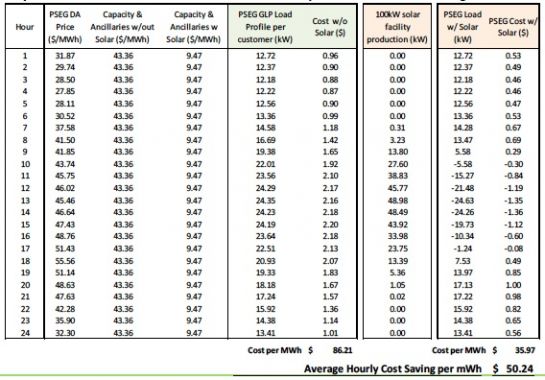

The second, representing a solar-equipped customer with an interval (smart) meter, shows the opposite, with extra costs transformed into cost savings:

To be sure, the presence of an interval meter isn’t the only barrier standing between REPs and the customer-sited solar game. “The main challenge for these retailers has been the tax credits, the third-party financing, and the market itself,” Kanlier said.

That could be why we’ve seen most REPs dive first into the business of selling green power to customers via contracts that buy power from wind, solar and other renewable resources. These green power purchasing programs are popular among customers interested in going green -- and that, in turn, has made what was a fairly rare offering into more or less a “pretty standard product” amongst the country’s REPs, eroding their value as competitive differentiators, Kanlier said.

These offers also come with a higher price for customers, which represent the pass-through costs of obtaining more expensive renewable energy, he said. Customer-sited solar, in contrast, can reduce the customer’s utility bills, while also providing them the satisfaction of going green.

Retailers may decide that partnering with established third-party solar providers is safer than creating their own offering. That’s what Direct Energy, a subsidiary of U.K.-based Centrica that operates in fourteen deregulated state markets, did with SolarCity in October, creating a $124 million fund to finance commercial and industrial rooftop solar.

But it’s pretty clear that other REPs are laying the groundwork for a wholesale assault on the business model of SolarCity et al. NRG CEO David Crane has been pledging a move into distributed energy, with promises of solar panels matched with natural-gas-fired home generation systems, now in development, to fill in the gaps that solar can’t.

This is an active, volatile market segment and one worth watching as REPs jockey for position in retail solar, helped by the 46 million smart meters currently in place.