The energy storage industry needs better financing to break out of its early stages. So far, commercial project financing is becoming more widely available, but residential financing has barely gotten started.

The high upfront cost of storage makes it hard for behind-the-meter customers to purchase out of pocket, and they can't call on the kind of capital available to utilities or large power producers. For financiers, meanwhile, energy storage poses several risks: It's a relatively new technology with emerging business models and revenue streams, both of which are subject to the influence of shifting tariff structures.

"If the energy storage market is going to grow beyond the early adopters, there's going to have to be more widely available, low-cost financing," said Brett Simon, a behind-the-meter storage analyst at GTM Research, who recently published a report on storage financing.

Here are the key indicators of where storage financing stands today.

Commercial financing is growing, with a clear pathway to success

The pool of project financing is swelling. It jumped from almost nothing in 2015 to $796 million in 2016, and the storage financing in 2017 hit 51 percent of that amount by mid-May. That money is going almost exclusively to commercial projects, although a growing cohort of lenders now at least cover residential storage.

The minimum internal rate of return needed to attract financiers ranges from the high single digits to the low 20 percent mark, according to Simon's latest research on the topic. The bulk of financiers are looking at the low to mid-teens.

Contracted revenue streams can cut the cost of capital for a project, the study notes. Capacity payments from utilities are an early form of this, and many utilities are examining new ways for distributed storage to provide grid services. Such an arrangement provides the lender with greater certainty that the storage installation will bring in revenue.

In all the cases where financiers accepted an internal rate of return below 10 percent, the project had a contracted revenue stream.

The majority of non-residential projects installed so far also feature demand-charge management as a key component.

"Today, demand-charge management is the major avenue through which non-residential storage projects seek to make their economic case, but this value stream alone is not enough to allow projects to pencil out in most U.S. geographies at the current juncture," the report notes.

With limited revenue streams currently available for storage, demand-charge management is relatively easy for developers to model and communicate to lenders and customers. In many cases, it needs to be paired with other value streams to make a project worth investing in.

Residential storage financing hasn't left the gate

Residential financing barely exists, at least in the U.S., because monetizable value streams for storage have yet to materialize in most markets.

A financier cannot yet monetize residential storage for backup, because this solution costs more than diesel generators. It's hard to take a cut of someone else's peace of mind.

Time-of-use rates are still rare for residential customers, and where they do exist, the delta between expensive and cheap retail rates is too small to reward shifting consumption. Residential demand charges are even rarer and less likely to provide a revenue stream.

Solar self-consumption and grid services offer the most promising avenues for residential storage financing, although the execution is still largely theoretical.

In markets with high electricity prices, low compensation for excess solar generation and other policy drivers, solar self-consumption is starting to make financial sense. Hawaii, Germany and Australia lead the pack on this. In such cases, a financier could lend money for a customer to install solar-plus-storage, and then capture a cut of the energy bill savings or value provided each month.

Grid services offer a contracted revenue stream from a utility. That gives the financier more certainty of payback compared to a contract with an individual homeowner, or a deployment where the homeowner can't draw revenue to pay off the expense.

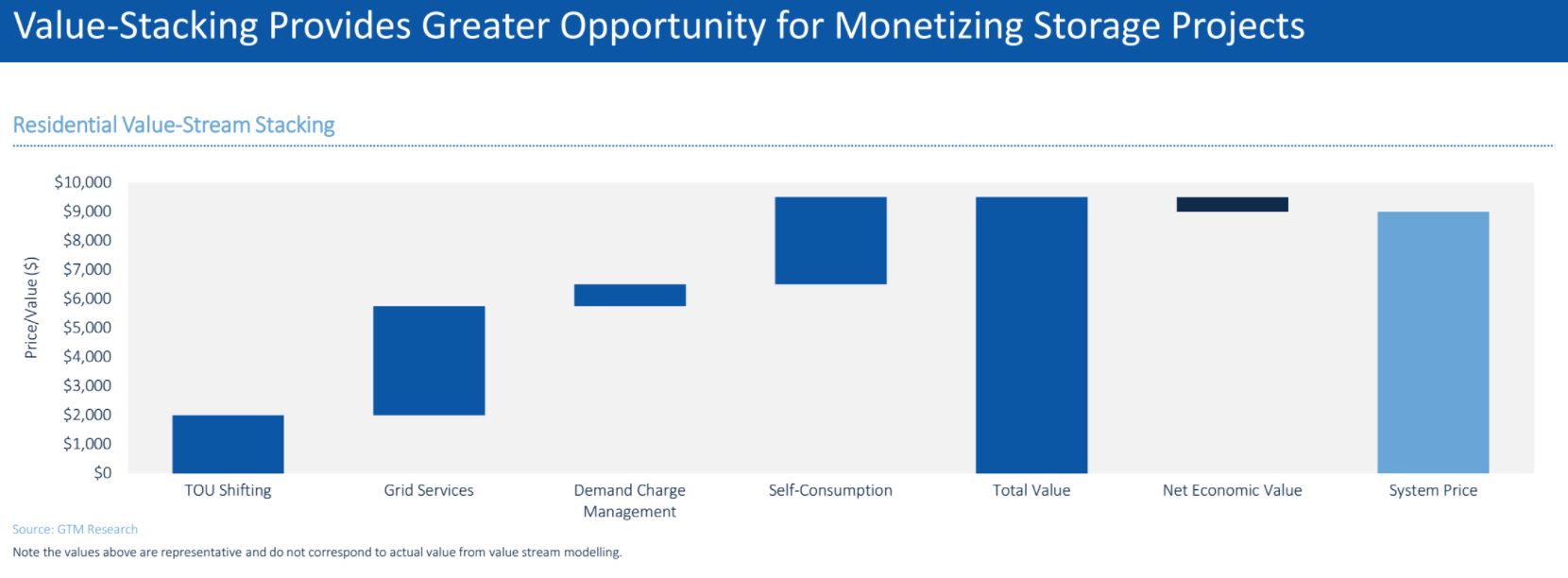

Because residential energy storage lacks clearly monetizable value streams, stacking multiple value streams within a single project may be necessary to make the project pencil.

So far, residential grid services have appeared in limited pilot projects; the model needs to go mainstream before there is enough of a market to make it profitable. For an early glimpse of what that might look like, check out the virtual power plant pilots at Green Mountain Power and Con Ed, and the Preferred Resources Pilot Program by Southern California Edison.

At least eight companies now offer financing for home storage, so there are options for customers who don't want to pay cash. GTM Research predicts storage eventually will follow the path of rooftop solar: as financing options grow, they will reach more customers, but the market will move away from leases to cash and loan deals by the mid-2020s to capture more value for the consumer.

Technology risk is less of an issue, but credit risk remains

Just a few years ago, lenders shied away from putting money behind a new technology that had limited run-time in the field and could possibly go up in flames.

These days, technology risk has faded as a concern for lithium-ion technology, according to the report. Most financiers consider this technology bankable, and vendors have enough data to offer performance and full-wrap warranties. Lenders tend to gravitate toward big, diversified providers that they believe will be around long enough to honor the warranty -- companies like LG Chem, Samsung and Tesla.

That technology risk still applies to the emerging lithium-ion alternatives, such as flow batteries and other exotic chemistries. Without many years of run-time or a brand-name backer, companies competing in this space have a heavier lift to convince lenders they'll get their money back.

Most of the developers and financiers interviewed for the study named credit risk -- the likelihood that the storage offtaker follows through with timely payments -- as their top concern. This worry will drive lenders toward larger C&I customers with lengthy credit histories and robust credit ratings, which could make it hard for smaller companies with limited credit history to secure financing.

Risk to financiers will decrease as the availability of contracted value streams for storage opens up. That requires policy and regulatory changes, which will unfold at varying rates state by state. That will be a complicated process, but storage, after all, is a complicated, multifarious technology.