Last week, parts of the Midwest and Northeast reached nostril-freezing temperatures, with windchill levels plunging below -60 degrees F in some areas.

Amid the dangerously frigid temperatures, the Trump administration’s recent policy efforts to boost coal and nuclear power meant there was extra attention paid to how different sources of electricity handled the cold. As residents across the Midwest and Northeast dug out of the deep freeze, power producers, regulators and experts assessed the results.

Reports suggest that nuclear, gas, coal, wind and solar all faced some challenges in the numbing cold, but generally fared well.

“On the whole, each asset class pretty much ran exactly as designed [and] expected,” said Brett Blankenship, research director at energy research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, who analyzed data culled from across the impacted regions.

But even as the industry commends the smooth functioning of the system, a shifting resource mix supplying electricity is creating fresh challenges. The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that renewables will be the fastest-growing sources of electricity for at least the next two years. At the same time, coal faces extreme headwinds as more and more plants enter retirement.

Managing the grid

The grid operators in the Midwest and Northeast, PJM Interconnection and the Midcontinent ISO (MISO), both prepped for the cold with weather advisories.

Despite putting all generators on deck with the declaration of a “maximum generation event,” MISO’s system, which services at least parts of 15 states and Manitoba, didn’t reach an all-time peak. The operator reported that the record set in 2014, when the peak hit 109.3 gigawatts, remained intact, edging out the January 30, 2019 peak of 100.9 gigawatts.

A spokesperson with Xcel Energy said the utility coordinated closely with MISO during the period of rock-bottom temperatures. Parts of Xcel’s service territory in Minnesota saw the lowest temperatures in two decades.

“Being part of a larger system like MISO helps ensure that we can meet demand in our service area during extreme conditions,” said the utility in a statement. “MISO called for maximum output during the cold snap, which we provided, as it operated under alert conditions.”

PJM did not call a maximum generation event, and according to Senior Director of System Operations Paul McGlynn, the operator at times was actually exporting power to MISO.

“We had ample resources throughout the event, plenty of reserves,” said McGlynn. Though PJM is still finalizing its data, McGlynn expects last week’s weather to rank fourth among all-time winter peak loads.

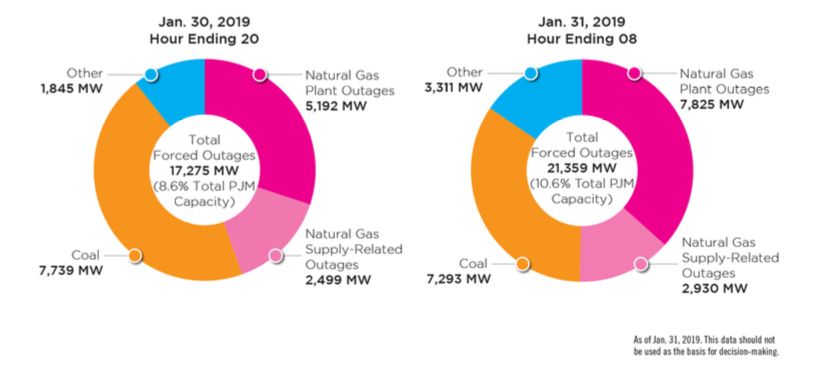

In a note summarizing operations during the cold, PJM — which manages electricity in 13 states and Washington, D.C. — reported that forced capacity outages were also lower in 2019 than in previous extreme weather scenarios. In the winter peak of 2018, for instance, PJM had 12.1 percent forced outages. The 2014 polar vortex was even higher, at 22 percent forced outages.

In comparison, forced outages on January 30 and 31 reached just 8.6 percent and 10.6 percent of capacity, respectively. McGlynn said the data is “certainly trending in the right direction.”

“The system is performing better,” he added.

PJM Forced Outages, January 30-31, 2019

Source: PJM Interconnection

This year’s mechanical outages were dominated by coal and natural gas (PJM's generation varies by time of year, but on the day this story was published the majority was divided between coal, gas and nuclear), with some gas supply outages as well on January 30 and 31. While PJM said forced outages “were slightly greater than normal,” it noted that that’s the norm in extreme cold events.

The resilience and resource debate

Though potential federal plans to offer financial support to coal and nuclear plants seem to have been shunted to the back burner, last week’s challenging weather once again brought those debates to the fore.

In most natural disasters, such as wildfires and hurricanes, damage to transmission and distribution causes the majority of electricity disruptions — something renewables advocates say can be managed with a distributed grid. But very cold or hot weather complicates those arguments, because the power generation source may be most impacted, either because of fuel shortages or mechanical issues caused by extreme temperatures.

While previous winters have brought reports of frozen coal piles and limited gas supplies, those were less of an issue last week than mechanical malfunctioning.

As noted in PJM’s report, both coal and natural-gas plants were taken offline due to mechanical issues.

In Xcel territory, the utility experienced low pressure on its natural-gas pipeline system in Princeton, a small town north of Minneapolis. The utility said it provided lodging and space heaters to customers until service could be restored. A spokesperson said Xcel is now working to identify possible solutions, including possibly adding infrastructure in the area.

Aside from the problems in Princeton, Xcel said it experienced no supply or usage issues with its coal or natural-gas generation. The utility did, however, ask consumers to moderate gas usage until temperatures rose. Consumers Energy, in Michigan, asked the same. A spokesperson with Consumers said the utility’s generation fleet “performed very well” during the cold, and the utility specifically noted that no coal generation was lost due to the weather.

A spokesperson with Commonwealth Edison, the largest utility in Illinois, also said all generation sources “performed as expected.” However, the utility did face some outages tied to transmission and distribution issues.

Mixed results for clean energy resources

For clean energy sources, results were similarly mixed.

In New Jersey, ice disrupted service at a nuclear reactor for which utility PSEG has requested subsidies to help support. Aside from that hiccup, Wade Schauer, research director of WoodMac’s Power & Renewables division, said “nuclear did amazingly well.”

Exelon, which partially owns the plant in New Jersey, said its plants in Pennsylvania, Illinois and New York operated at full capacity through the low temperatures.

Schauer said wind was the most volatile resource.

“We expect wind to be volatile,” Schauer said. “But during extreme events, volatile or intermittent generation makes managing the grid more challenging.”

In PJM’s analysis, renewables fit in the “other” category for forced outages (in the figure above), with 1,845 megawatts going offline on January 30, and 3,311 megawatts going offline on January 31. Forced outages on Jan. 31 also include the roughly 1.1-gigawatt nuclear reactor in New Jersey.

While McGlynn said PJM definitely experienced wind-related issues, he expects there were solar outages, too. The grid operator is still working on analyzing that data.

In extreme temperatures, solar panels can be less efficient than during normal operation. Batteries are also able to store less power. And wind turbines often can’t function in extreme cold, which can ice over blades, or in high winds.

“This does not mean renewable energy is not good, but it just means different types of generation have different features,” said Zhaoyu Wang, a professor of electrical and engineering at Iowa State University.

Xcel noted that its wind farms in North Dakota and Minnesota reached the low temperature threshold at which they automatically stop operating on the night of January 29. They remained offline until noon the next day.

Overall, grid operators and utilities felt the system handled the bracing cold well. But that system is changing, with more renewables and gas and less coal. Operators note that severe winter storms in the past have been instructive, but strategies to keep electricity and heat available will have to change as the grid does.