Building a technology platform to control distributed energy resources such as rooftop solar systems, behind-the-meter batteries, EV chargers and flexible electricity loads is a challenging enough task. Identifying ways to measure their economic value as grid-balancing agents and run real-time markets that can entice them to respond with grid-friendly actions adds another layer of complexity.

Ontario, Canada-based startup Opus One Solutions says its GridOS Transactive Energy Management System can handle the task. Now it’s putting the system to the test in a first-of-its-kind pilot project in California.

Over the past three years, Southern California Edison and a long list of partners have been working on a U.S. Energy Department grant-funded project, dubbed Electric Access System Enhancement (EASE), aimed at creating an “interoperable distributed control architecture” for its low-voltage grid. So far, it’s been tested on a computer-modeled fleet of 10,000 virtual distributed energy resources (DERs).

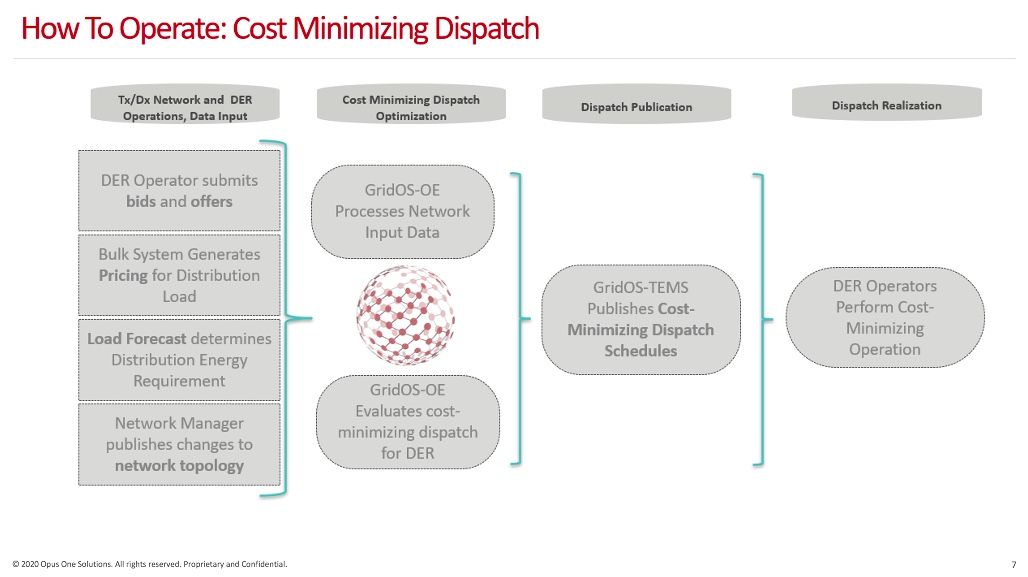

The next step will be enrolling customers in the grid-constrained Orange County city of Santa Ana for a real-world test of using price signals to charge and discharge batteries or curtail PV output or energy consumption. Opus One’s role is to model distribution grid power flows to identify constraints, analyze the universe of DERs that could help resolve those constraints, and create dispatch schedules and price signals to entice them to do so, all in close to real time.

“The industry term for this is security-constrained economic dispatch,” said Ben Ullman, Opus One’s lead product manager for transactive energy. “Historically, that’s only been done in the bulk system” via the markets run by transmission grid operators. But with Southern California Edison, the company is "bringing that to the distribution system with live customers.”

Holy grail of DER-distribution grid orchestration

SCE describes the system it’s working on as “a distribution system operator platform,” a concept that’s something of a holy grail in the grid edge world. It’s also been devilishly hard to translate into reality from the starting point of traditional utility and grid operator systems, which aren’t designed to manage the massive calculations to solve for how DERs can help manage local grid disturbances.

It’s taken a lot of work for SCE and its EASE partners to solve these kinds of disconnects, Ullman said.

SCE has invested billions of dollars in grid modernization to collect, organize and analyze the data required to offer a clear picture of its distribution grid operations. “The SCE network models are quite detailed," Ullman said. "SCE knows not only where DERs are and where aggregations of DERs are, but also the capabilities of those DERs and the hardware they’re connected to.”

Smarter Grid Solutions, another EASE partner, has contributed important pieces of the puzzle. The U.K.-based company has created a platform that combines DER permitting and interconnection processes for SCE and assigns each new DER a unique digital ID with a “self-provisioning” process that connects them to SCE’s centralized distribution grid control platform.

Smarter Grid Solutions also provides its distributed energy resource management system, which embeds DERs with sensors and controls allowing them to respond to local events at the feeder circuit and substation level that centralized control platforms can’t act quickly enough to solve.

Platforms like these can control DERs that are actively enlisted in their systems to manage grid constraints. But Opus One is taking the next step to model the system impacts of DER activity, the economic costs of constraints and the value of DER actions that can solve them, said Mark Hormann, Opus One’s vice president of U.S. sales.

From there, the GridOS platform can calculate location- and time-specific dispatch schedules that minimize costs or losses in the system, and set nodal prices for the cost of an incremental unit of load from moment to moment, he said. “Getting prices to devices, and getting them to interact in real time, is the goal,” Hormann said.

Extending DER prices to devices from distribution to transmission level

Regulators in California, New York and several other states are pressing utilities to increase DER hosting capacity, measure their positive value for the grid, incorporate them into day-to-day grid operations and include them in long-range grid plans and investments. SCE has been a vanguard utility on this front, with long-running contracts with DER aggregators to supply grid capacity, and more recent ones aimed at testing the price-responsiveness of residential solar-storage systems.

Opus One’s work on New York utility National Grid’s Distributed System Platform pilot project was an early step toward this kind of price-based dispatch system, Ullman said. “The high-level goal was to demonstrate that location- and time-specific price signals could be passed on to DERs,” as all utilities in New York will eventually be required to do under the state’s Reforming the Energy Vision initiative.

Another project with utility Ameren in Missouri and Illinois built on this by incorporating bulk transmission system values alongside distribution grid values in a “DER simulator” that could assess the value of distributed energy at both scales, he said. That experience has come in handy in enabling the final goal of SCE’s EASE project — to find ways to integrate DERs with the markets run by California grid operator CAISO.

Opus One’s day-ahead and 15-minute intraday optimizations work on the same time scales used by CAISO to dispatch bulk power system resources, Ullman said. That could include the solar PV and battery systems being targeted for EASE’s real-world trials, or electric vehicle chargers, grid-responsive water heaters or other demand-response-capable loads, he said.

This could open up a much broader set of DERs now outside a utility’s reach to becoming market-based agents. SCE still has to prove that the technology combination its EASE project is putting together works under real-world conditions. But “as it becomes standardized, we can roll this concept out across entire utilities or entire markets,” Ullman said.