Even though records were broken last year in terms of wind power installations, the rate of growth continued to decline compared to previous years. Unfortunately, offshore wind power was, with the exception of a small handful of nations, a sideshow to onshore wind power.

This is particularly striking in the United States, which has the second-largest amount of wind power installed in the world and virtually tied for most new installations last year, where there still is not a single completed offshore wind farm -- even though there are several planned, including the over-a-decade-in-the-works Cape Wind.

A Fraction of a Fraction of Power Generation

Global offshore wind power, at the end of 2012, totaled 5.4 gigawatts, concentrated, with but two exceptions, both in Europe. For comparison, total global wind power capacity now tops 282 gigawatts; new installations alone last year were nearly 45 gigawatts.

Though the United Kingdom ranks sixth in terms of overall wind power capacity, with 8.5 gigawatts, it leads the world in offshore wind power by a huge margin -- not surprising considering it’s an island nation, with very high population density and an ancient connection with the sea. Last year the U.K. installed a bit over 850 megawatts of offshore wind power, bringing the national total to 2.95 gigawatts.

The second-ranked nation, Denmark, trails far behind, with a total of 921 megawatts of offshore wind power, just 47 megawatts of it installed last year. China occupies the third spot, with 390 megawatts (in two projects), 127 megawatts new for 2012. Belgium, Germany, and Netherlands round out the fourth through sixth places on the list, as well as being the only other nations with over 200 megawatts of offshore wind power.

As one delves more deeply into the rankings, it becomes slightly absurd. Though in an absolute sense both Norway and Portugal have some offshore wind power capacity, it’s so low (2.3 megawatts and 2 megawatts, respectively) that it bears asking whether a project with fewer than five turbines really counts as a commercial wind farm, except in a technical sense that it does generate power for money.

Currently, the three largest offshore wind power project are, not surprisingly, in the U.K.: the 504-megawatt Greater Gabbard wind farm, the 367-megawatt Walney Wind Farm and the 300-megawatt Thanet project.

Much larger projects are in the works though, and frankly have been for what seems like forever. Projects in various stages of completion just topping the two U.K. projects named above, going all the way up to the 1,000 megawatts London Array, always seem to be just a little while away from completion. Truly massive, multi-gigawatt projects have been proposed for the North Sea, but these are a ways off.

U.S. in Second Place Overall, But Offshore Projects Languish

In the U.S., not only have no offshore wind power projects been completed, but little even approaching this scale is even being contemplated -- even though reports have shown that offshore wind power alone could power the entire East Coast.

A sampling of projects currently at one stage or another of planning or proposal include a 30-megawatt project off Block Island; a project off the coast of Maryland (currently on hold); a 12-megawatt project off the coast of Texas; and a 20-megawatt project in Lake Erie (yes, offshore wind power can mean freshwater, too).

And then there’s Cape Wind. Initiated over a decade ago, and subject to an intense back-and-forth battle for approval, the 24-square-mile project in Nantucket Sound is planned to have 130 3.6-megawatt turbines. It’s currently the only offshore wind power project in the U.S. to have all its permitting in place. The most recent estimate for completion is for it to begin producing electricity in 2015, with it coming to full capacity in 2016.

For over a year now, the Obama administration, acting through the Department of Interior (which handles resources on the continental shelf), has technically fast-tracked offshore wind power development, streamlining offshore wind power approval off New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia.

At the time, Kit Kennedy summed up the situation for NRDC Switchboard. Though a year old, it pretty much still stands as an accurate assessment:

“The process for getting offshore wind power off the ground in this country takes far too long. The projected timeline for approval of an offshore wind project is currently seven to nine years, far longer than the typical siting process for a fossil fuel power plant (which is two to three years). It’s a crying shame that it has taken so long to get clean, homegrown offshore wind turbines up and running while fossil fuel power plants, with their plethora of health and environmental impacts, can be green-lighted in a fraction of the time.”

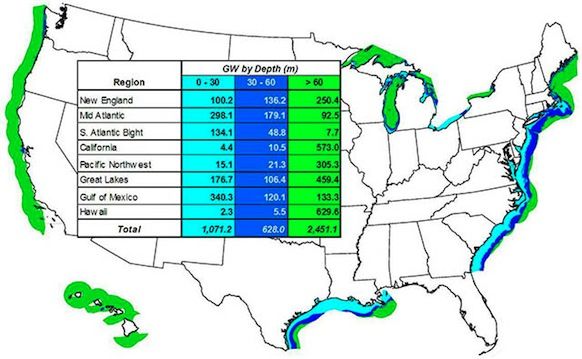

Image: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

As for the potential for offshore wind power in the U.S. waiting to be tapped, check out the chart above. Adding that all up, tallying the potential at different water depths, it’s 4,180 gigawatts -- more theoretical potential than all of the U.S.’s current electricity capacity from all sources by a factor of four. Even taking into consideration that the far right column involves putting turbines into water depths greater than is currently done, it’s still more power than is currently being generated.

Here’s the really sobering part (or encouraging part, depending on your mood): Wind power right now provides just 3.46 percent of all the electricity generated in the U.S. So little, but so much room for expansion -- and reduced environmental impact.

***

Editor's note: This article is reposted in its original form from EarthTechling. Author credit goes to Mat McDermott.