Natural-gas power generation in the U.S. saw its biggest annual decline yet in 2017, with net generation from the resource dropping 7.7 percent. Coal generation also fell, at a more modest 2.5 percent, marking the first time in a decade that both resources faced declines.

At the same time, data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) showed net generation from utility-scale clean energy sources, excluding hydro, grew by 13.4 percent. Meanwhile, total U.S. net generation fell by 1.5 percent last year.

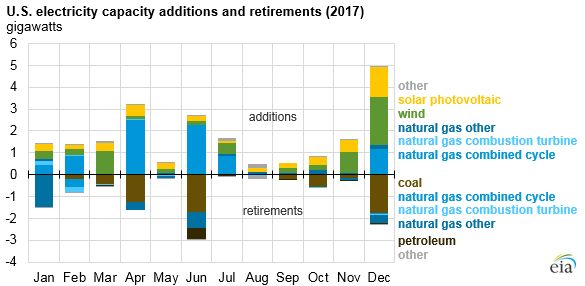

Just over 11 gigawatts of power generation was retired last year, including 6.3 gigawatts of coal and 4 gigawatts of natural gas -- mostly of steam turbines.

Despite these shifts, natural gas remains at the top of the U.S.’ list as a fuel source. The country also added 9.3 gigawatts of natural-gas capacity in the last year -- mostly from combined-cycle units. But the current reign of natural gas comes alongside growing consideration of a gas-free future.

While environmentalists have long decried what many have called a “bridge fuel,” utility commissions in forward-looking states are also now starting to strategize about how to leave natural gas behind.

“At some point soon, we’ll be permitting the last gas plant in California,” Robert B. Weisenmiller, chair of the California Energy Commission, recently told The Wall Street Journal.

A fight over a plant in Oxnard crystallizes much of California’s tussle over natural gas. For years environmental justice and clean energy advocates lobbied against the natural-gas-fired Puente Power Plant, arguing it could be replaced with cleaner sources. In November NRG paused its application for the plant, signaling a symbolic suspension of the debate if not a complete end. In March NRG went further, announcing it would also close three of its existing natural gas plants in California by the first day of 2019.

In January, the California utility commission ruled that the state’s largest utility, Pacific Gas & Electric, should procure energy storage or clean energy resources to replace three existing gas plants.

And it’s not just California moving away from gas. Clean energy generation increased in all but nine states between 2016 and 2017, according to EIA data. In that same period, net generation from natural gas increased in just 12 states.

Arizona recently made an unprecedented move in placing a nine-month moratorium on any new gas plants larger than 150 megawatts. Instead of relying on gas, commissioners will now consider resource plans where clean energy accounts for a large percentage of generation.

In Michigan, a ballot measure would bump the state’s share of clean energy to a minimum 30 percent (it doesn’t have the support of utilities). The state’s public service commission recently released a report that noted clean energy is getting closer to economic competitiveness with natural gas.

Separately, Michigan has experienced opposition to a new 1.1-gigawatt gas plant that advocates say could be replaced by a portfolio of resources including solar and wind.

A report last year from Minnesota researchers found that solar-plus-storage could beat out simple-cycle natural gas peaking plants by 2022.

Results like those are what spurred Shayle Kann, senior vice president of research and strategy at Energy Impact Partners, to declare, “I can’t see a reason why we should ever build a gas peaker again in the U.S. after, say, 2025.”

Many of these plans are forward-looking, in part because utilities move slowly, but also because natural gas still maintains an economic edge. Many states are still considering and building pipelines and gas plants. Other data coming out of the U.S. suggest the country won’t be giving up on its No. 1 fuel just yet.

Instead, it’s spreading it around the world.

In 2017 the U.S. exported more natural gas than it imported for the first time in 60 years, fueled by production that “increased significantly over the past decade,” according to EIA.