A handful of billionaires have shaped and guided the cleantech industry’s development: Elon Musk through his chaotic but visionary leadership; Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos with their moonshot investments.

Now there’s a new billionaire in town.

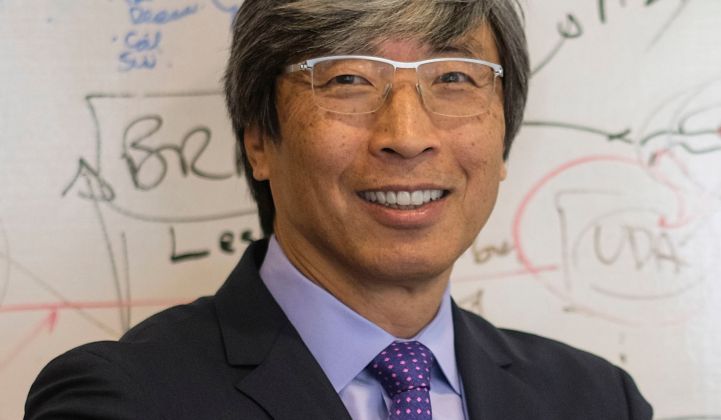

In just a few months, surgeon and medical entrepreneur Patrick Soon-Shiong announced his acquisitions of two energy storage companies: Fluidic, the exotic zinc-air battery company with 3,000 systems deployed in remote areas, and Sharp’s commercial storage development unit, dubbed SmartStorage. They are now reconstituted as NantEnergy.

An investor with billions of dollars at hand could look elsewhere for surefire profits. The storage industry remains small, and the long-duration sector has been marked by many failures and few outright successes.

“What I saw, frankly, was the impact this would make,” Soon-Shiong told GTM earlier this month. “It wasn't a true business analysis, [like] ‘What's the return?’ If it was successful, the return organically would be fantastic. If it weren't successful, it's binary, as most of these companies have shown.”

Now he will set about making his mark on the cleantech industry, which has long grappled with the “valley of death” that cleaves promising hardware from fully capitalized commercial deployment. Great personal wealth may succeed where venture capital largely has not.

Science-based business

Soon-Shiong intends to participate in NantEnergy beyond mere financial backing.

“I don't see myself as a financier; I see myself as a partner in the scientific challenge to make a difference,” he explained.

In particular, Soon-Shiong wants to contribute to Fluidic’s battery technology based on his long and fruitful relationship with zinc. That’s not something one typically hears from investors on Wall Street or Sand Hill Road.

Soon-Shiong investigated zinc for his earlier medical work on pancreas transplants and diabetes. He dug into cell-level zinc transport dynamics during a stint with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he produced cells that would make insulin in a space shuttle.

He used the protein albumin to achieve the necessary zinc transport. Later, Soon-Shiong turned the albumin into a nanoparticle designed for chemotherapy, which evolved into the drug Abraxane. In 2010, he sold the company that produced the drug to Celgene Corp for $3 billion.

“If you look at this wild ride in a sort of scientific, iterative approach, I needed to understand everything about zinc, I needed to understand everything about what zinc binds to, what releases zinc and what attaches and detaches to zinc,” Soon-Shiong said.

Those principles apply directly to Fluidic’s quest to harness zinc for charging and discharging batteries without forming dendrites.

“The science of the zinc-air battery to me made complete sense,” Soon-Shiong noted. “I not only get that, I think I can add to that.”

Solving the thorny long-duration storage problem isn’t the billionaire’s only self-imposed challenge.

As he laid out in a keynote at Energy Storage North America this month, he’s also at work on curing cancer, crafting solar-powered potable water plants, designing containerized hydroponic farms and genetically engineering bacteria to replace petroleum-based plastics. He also bought the L.A. Times in an effort to revitalize business models for delivering quality journalism.

NantEnergy's zinc-air batteries stack up to support solar-powered microgrids, but could go utility-scale in the future. (Image credit: NantEnergy)

Money to spend

The new ownership for the two storage companies may pay scientific dividends over the years, but Soon-Shiong’s money will go to work right away, funding construction of a factory to mechanize production of zinc-air systems.

The commitment creates security for the former Fluidic team to develop its technology without having to deliver a quick return for investors. Experience with the multi-decade biomedical product development cycle gave Soon-Shiong patience that the typical venture capitalist can’t afford.

“In my entire life, I took one VC investment, and never again,” he said. “It is not the model, sadly, for these long-term, high-impact businesses.”

After buying into the remote microgrid market, Soon-Shiong doubled down with his investment in commercial storage, another subsegment that has barely gotten off the ground outside of California’s subsidized market.

NantEnergy now controls both a leading long-duration lithium-ion alternative technology and a veteran commercial developer that pitches customer savings from solar and lithium-ion batteries. Soon-Shiong refers to the two approaches as the marathoner and the sprinter.

“When you look at NantEnergy's capabilities and you look at my team's capabilities, it's like two non-overlapping jigsaw pieces,” said Carl Mansfield, who founded the unit at Sharp and now serves as NantEnergy's vice president for system solutions.

The two units complement each other geographically: Fluidic has deployed almost entirely overseas, while SmartStorage focused on the U.S. Operationally, lithium-ion delivers fast ramping power, while zinc-air stores energy over hours and even days.

The company has already installed 600 systems that combine both battery technologies, Soon-Shiong noted.

SmartStorage distinguished itself as an unflashy developer amid a cohort of venture-backed commercial storage contenders. While other companies talk about the network effects to be gained from “value stacking” — serving a customer’s demand charge and participating in aggregated grid services, to deliver more project value — Mansfield took a more skeptical approach.

“We support fleet dispatch of our products right now, but we haven't seen an economic business case that really makes sense,” he said. “If you need value stacking to make the initial sale palatable to the customer, you're going to have big challenges in my opinion, because value stacking is not as easy as people like to claim it is.”

As a division within the massive Sharp corporate structure, the SmartStorage team had to evaluate each project on a profit and loss basis.

“We weren't an equity-based organization — spending money to build pipeline and market share had no value to us,” Mansfield said.

In 2016, Foxconn acquired Sharp for $3.5 billion, with a strategic focus on its consumer electronics business. The 12-person, U.S.-based commercial storage business didn’t fit neatly into that vision.

Now the team is part of a company wholly dedicated to installing battery storage. The financial situation could allow SmartStorage to use balance-sheet financing to offer storage as a service, which eliminates high upfront expenses for the customer. This approach makes sense for storage, but contrasted with Sharp’s corporate orientation toward hardware sales.

Mansfield wouldn’t comment on how much capacity his team has installed to date, but said he wants to scale “fairly rapidly” to deliver multi-tens of megawatt-hours per quarter.

“We're expecting to be one of the major market share holders in the U.S. C&I segment going forward,” he said.

Scaling this business, with its established technology, requires financing and execution. Compared to designing cancer-killing nanoparticles, even commercial storage looks easy.

--

Now in its fourth year, GTM's Energy Storage Summit will bring together utilities, financiers, regulators, technology innovators, and storage practitioners for two full days of data-intensive presentations, analyst-led panel sessions with industry leaders, and extensive, high-level networking. This year, we're expanding our traditional U.S. event to cover the global market. Learn more here.