Tough times don’t last, but small wind does, according to Bill Bergey, President of small wind sector standout Bergey Windpower and President of the Distributed Wind Energy Association.

Bergey went into the business in 1977. By the mid-1980s, Carter-era incentives were disappearing, natural gas prices were plunging and Bergey’s competitors were dropping like dominoes. “Almost all of them were out of business by [1987],” Bergey said. “We saw a 90 percent revenue drop in two years. There was almost room left for one company.”

Bergey named two keys to his company’s survival. “We had the most reliable name brand with the lowest warranty cost,” Bergey said. And they went out and found new markets, supplying off-grid electricity for emerging North African and Indonesian rural electrification programs.

Three-fourths of Bergey Windpower’s 1- and 10-kilowatt turbines now sell domestically (as will the soon-to-debut 5-kilowatt model aimed at newer, more efficient homes). The other quarter still sells internationally. “But there were times when those numbers were reversed.”

2009 and 2010 were good years for Bergey, thanks to the Recovery Act’s extension of the 30 percent investment tax credit (ITC) for small wind. Bergey Windpower saw a 50 percent year-on-year sales volume growth in 2009. Final 2010 numbers, Bergey expects, will show 20 percent to 30 percent growth.

But 2011, he said, will be a different. “A lot of companies will be happy to tread water.” Though small turbines have barely penetrated the estimated 12 million to 15 million homes in the U.S. that comprise the potential market, the flailing economy will impede growth. People don’t absolutely need such “big ticket items” -- and “even if they really want one, they can put it off,” he said.

Back-of-the-envelope figures on Bergey’s 10-kilowatt machine (on a 100-foot guyed tower) put the basic cost at about $64,000. The 30 percent federal ITC, in place through 2016, reduces that by $18,000. State rebates (such as California’s) often reduce the price as much as another $25,000 to $30,000. “That puts the out-of-pocket cost at about $21,000,” Bergey estimated.

In appropriate small wind turbine conditions, an owner can expect to generate 1200 to 1500 kilowatt-hours per month. A typical customer, Bergey said, may pay something like 24 cents to 32 cents per kilowatt-hour. In round numbers, he calculated quickly, that is a return of around $4,200 per year and a three- to five-year payback period on a product that has a 10-year warranty, regularly performs in the real world for 25 years and is designed to function for 50 years.

Bergey foresees “even-to-no growth” in 2011, based on expectations in this troubled economy. The first quarter of 2011, he said, “was not pretty.”

But the energy business has always been cyclical. “Right now, we’re at a low on energy savings and environmental stewardship,” he said. “But it will swing back.”

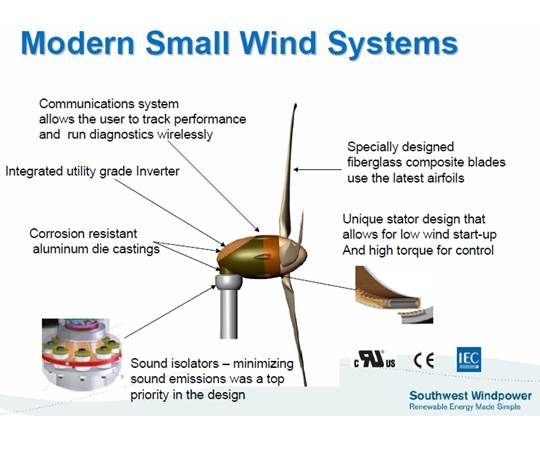

Andy Kruse, co-founder and Business Development Vice President for Southwest Windpower, was a cattle rancher in New Mexico in 1986, looking to solar and diesel generators to stay completely off-grid. Thinking wind might complement them, he and partner David Calley built a small turbine.

Just as Mike Bergey’s company was emerging from the downturn in 1987, Kruse and Calley took the evolved version of their turbine to the marketplace. They have since found 180,000 buyers in over 120 countries and maintain a staff of 80 to 90 employees.

The first big jump for Southwest Windpower’s market came with breakthrough inverter technology that allowed distributed wind generators to cost-effectively connect to the grid. That increase in business potential brought backing from GE, Chevron and a handful of other deep-pocketed investors, allowing development of the company’s successful Skystream turbine line.

With support from Washington Congressman and rancher Earl Blumenauer and others on Capitol Hill, Kruse and small wind lobbyists pushed through federal incentives that drove market growth between 2008 and 2010 -- but not this year. “Markets are down probably 30 percent from the peak,” Kruse said. “There are a lot of challenges in the domestic market.”

But there are other opportunities. “The rest of the world is growing,” Kruse said. Noting “big orders” from Brazil, Chile, Spain, Korea and India, he said, “We think that’ll be back to where we were a couple of years ago by either the end of this year or the first part of next year,” though Southwest Windpower’s manufacturing facility remains in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Bigger machines sell better domestically, Kruse said, because U.S. per-capita energy consumption is so high. Southwest’s flagship 2.4-kilowatt turbine, which sells at the rate of 300 to 400 units per month, he said, is more suited to emerging economies for both grid-tied and off-grid applications.

“The telecom market is just exploding,” Kruse said. “We’re displacing diesel systems” which, due to refueling costs, price out at as much as 40 to 75 cents per kilowatt-hour. Small wind systems can power the same cell towers on remote African and Asian mountaintops at 12 cents to 15 cents per kilowatt-hour. Hybrid systems incorporating wind or solar and diesel generators marry reliability and cost effectiveness.

“The international micro-scale market for electricity is growing fast,” Kruse said. “More ... of the world is middle-class now. There are more than 4.3 billion cell phones.” Building solar or small wind systems for those consumers is more cost-effective than new transmission. And improvements in scale and efficiencies will make them cheaper.

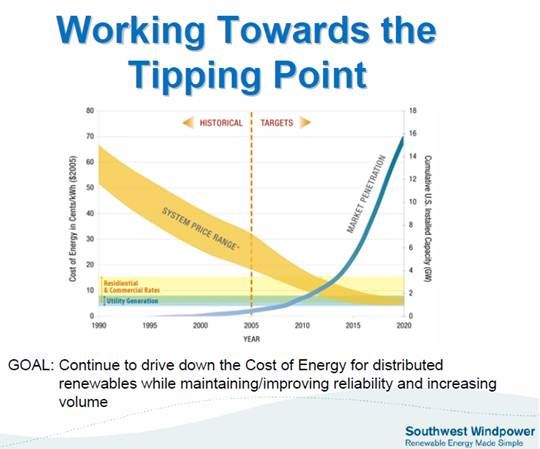

“When we first started, small-wind-generated electricity was costing 50 or 60 cents per kilowatt-hour,” Kruse concluded. “We’re down to 12 to 15 cents. And we could probably drop another 40 percent to 50 percent over the next decade.”