Riddle me this: In Western China, does the wind blow harder than the sun shines?

In January, as soon as China raised its solar 2015 solar target from 21 gigawatts to 35 gigawatts, the question arose of how this would affect the country’s struggling wind market. After all, the apparent purpose in raising the solar target was to support the domestic solar manufacturing sector, currently facing global production overcapacity and financial troubles epitomized by the ambiguously bankrupt industry champion Suntech. Around the same time, China also announced specific 2013 installation goals: 10 GW for solar, 18 GW for wind, and 21 GW for hydroelectric. Impressive goals for solar, but not for wind. If China installs 10 gigawatts of solar in 2013, that would more than double the 2012 installation rate, whereas for wind, 18 gigawatts would only hold the market steady.

So is China now favoring solar over wind?

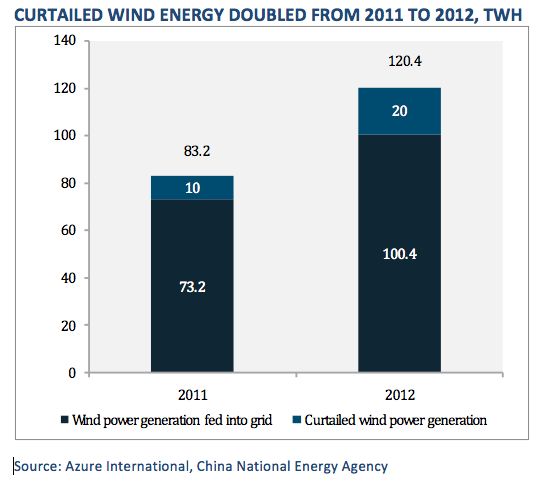

Wind and solar are located in the same areas: China’s wind and solar resources overlap, worsening the situation for wind if the government decides to give solar priority. The sunniest and windiest regions are located in the north and west. Because China has so much wind power already located in lightly populated places like Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Gansu provinces, wind developers suffer curtailment when local demand and transmission are insufficient to handle the power. (The problem keeps getting worse: in 2012, curtailed wind energy doubled from the prior year. And on one day earlier this year, wind accounted for 92 percent of all power supply in East Inner Mongolia.) Wind developers have gradually shifted away from these regions, but the alternatives (such as coastal provinces) are also potential places for solar.

Competition for interconnection isn’t severe: One positive aspect for wind is that interconnection may not be a competitive advantage versus solar. The interconnection processes for wind and solar are similar. For the most part, it is simply a matter of the developer’s place in the queue, though grid management issues obviously play a part. To the extent that the wind market is more developed and grid companies have more experience with wind, that helps the approval process for wind. But to the extent that solar projects are easier for the grid to manage and can get built faster, this helps solar. Indeed, in China, the grid connection process for utility-scale projects is the opposite of those in other countries: Under China’s if-you-build-it-they-will-come practice, developers put the project on the ground well before interconnection. This could mean more bottlenecks as solar grows.

Wind and solar are competing for feed-in tariff subsidy payment: Payment delays for feed-in tariffs that support renewable energy are a problem that could last for years, whereas delayed connections are a short-term issue. Curtailed power is currently not compensated, and the government is only now talking about policies to accurately measure curtailment at the wind-farm level to enable future compensation.

Equally important are the payment delays that can take place in areas with too many renewable plants relative to local load. For Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Gansu, the government has been slow to order other provincial grid companies to make the inter-provincial transfers needed to keep feed-in tariff funds flowing. (The feed-in tariffs are paid by provincial grid companies to plant operators out of funds collected through a surcharge on most electricity customers.) The problem will only get worse if there is a sudden doubling in solar installations in these areas, since solar is compensated at an even higher feed-in tariff rate. (Tariffs range from RMB 0.75 to 1.00/kWh for utility-scale solar, compared to RMB 0.51-0.61 for wind. Azure estimates 10 gigawatts of solar would consume almost as much subsidy funding as 40 gigawatts of new wind.) When payments slow down, state-owned developers have no choice but to pass along the delays to their suppliers. Paradoxically, if the problem gets worse, that could speed the government’s desire to resolve the issue for all renewable players, since late payments would hurt the very companies the new solar targets are supposed to help.

Wind and solar are competing for state-owned developer funding: The major wind developers in China are large state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and they are also developing solar and other power plants. So when policy targets and incentives change, they will shift resources to whichever project offers them the best return. To the extent solar and wind developers are the same entity (large SOEs), there is competition between wind and solar for investment RMBs. Policies that improve returns for solar would therefore tilt investment toward solar and away from wind. But there are many instances where wind and solar projects are complementary. For example, if a developer already has a solar project in place, staff and land can be shared to some extent, and grid connections might be easier depending on the nature of the power flows.

Wind and solar project financing is totally different: In terms of financing for renewable projects, the overall picture is quite different from other countries. The vast majority of financing comes from state-owned banks and is directed toward large state-owned energy companies that develop projects. Interest rates are fixed, but the central government can dial up lending or dial it back depending on macroeconomic objectives or industry-specific policy goals. Most large renewable energy projects are simply financed through general corporate balance sheets of SOEs, and bank lending is non-recourse general corporate debt. Otherwise, only when a project is on the ground and has been receiving steady cash flows would it qualify for project-based lending, unlike in other regions, where project financing is critical to building the project.

Government promotion of distributed solar could help separate that market from wind: All other things being equal, a large wind manufacturer like Goldwind would prefer if most new solar GW went toward distributed wind projects in large cities, essentially creating two separate markets. The government has promoted distributed solar for years, and the new 35-gigawatt target includes 10 gigawatts of distributed solar. The Golden Sun program to subsidize distributed solar has approved 4.5 gigawatts in projects, including 2.8 gigawatts in the second round to be completed by mid-2013. Under Golden Sun, which began in 2009, building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) projects could initially receive RMB 20/W for BIPV systems and RMB 15/W for BAPV (building-applied PV, or rooftop) systems. In 2012, the subsidy declined to RMB 7/W for BIPV and RMB 5.5/W for BAPV. Qualified on-grid photovoltaic electricity generation projects including rooftop, BIPV, and ground-mounted systems are entitled to receive a subsidy equal to 50 percent of the total investment of each project, including associated transmission infrastructure. Qualified off-grid independent projects in remote areas will be eligible for subsidies of up to 70 percent of the total investment.

Recent announcements have suggested that after this phase the Golden Sun program will end and be replaced by a more efficient subsidy scheme. State Grid has also made grid interconnection easier for distributed renewable energy.

Distributed solar economics depend on regional tariffs, sun: According to policies under consideration by the NDRC, distributed PV owners will receive a RMB 0.35-0.5/kWh subsidy on all energy that is produced and consumed locally. Analysts had originally anticipated a subsidy of between RMB 0.4-0.6/kWh on all electricity produced.

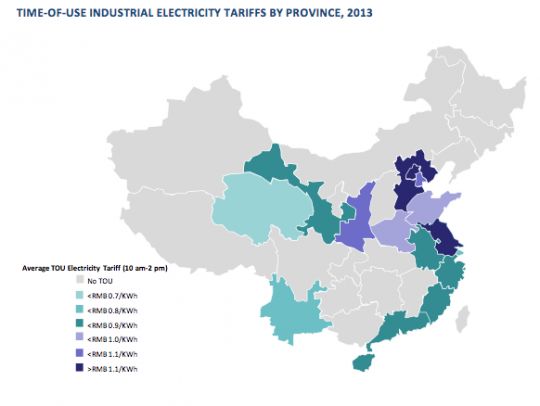

The attractiveness of this new subsidy varies. PV system owners will look to have high self-consumption because they both avoid electricity purchases from the grid, which can range from RMB 0.5/KWh for residential to RMB 1.35/kWh for some commercial and industrial loads, and receive the subsidy. At current PV prices, the subsidy is not enough to justify investment in residential systems. However, the economics for commercial and industrial installations in regions with high electricity tariffs and ample solar resources are workable. For example, an industrial factory owner in Jiangsu could receive a 13 percent IRR by installing a $2,500-per-kilowatt system.

Provinces and cities with high average retail tariffs during peak solar production hours, as well as above-average solar resources, promise the best return on investment and are logical launch points for future distributed PV development. Developers will need to look for overlaps. The figure below shows average retail pricing for provinces with time-of-use rates. Provinces with flat daily rates tend to have lower electricity tariffs during peak solar generation times.

Foreign investment isn’t really on the map: In thinking about financing, it’s important to recognize that the renewable energy development field is relatively closed to foreign investment, though that closure is not total. Roughly a half-dozen foreign wind farms have been developed, funded by private developers through a variety of conventional means, and only one solar farm has received foreign development dollars. Given the state of the industry and feuds with foreign countries about renewable energy subsidies and anti-dumping cases, China seems unlikely to suddenly open the doors to foreign private companies.

However, a more closely watched issue in the near term is whether the government pursues reform efforts in the state sector. Recently, there has been more talk of splitting up State Grid, for example -- the grid company that controls most, but not all, of China’s provincial power grids. If China’s new leadership really embarks on a major reform and opening of the state power sector, while pressing on with aggressive renewable energy targets, it could matter much more for clean energy than raising official targets.

***

Anders Hove is manager of cleantech research at Azure International.