India has made tremendous commitments toward its goal of installing 100 gigawatts of solar energy by 2022. In the first three quarters of 2015, various stakeholders have committed more than $100 billion to renewable investment in the next five to seven years, according to a new study by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

“The smart money on India today is in renewables,” Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies in Australasia for IEEFA, wrote in a blog post. The Indian government estimates it will take about $200 billion to finance its clean energy goal of 175 gigawatts of additional renewable capacity by 2022, up from 36 gigawatts today.

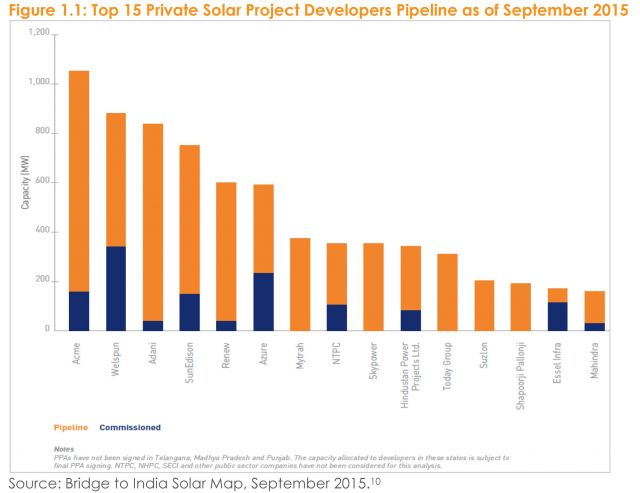

The IEEFA report pointed to $100 billion in firm commitments, all of which are outlined in the report, including $20 billion by a joint venture between SoftBank, Japan, Bharti Enterprises and Foxconn, Welspun Energy’s goal of 11 gigawatts of renewables with a price tag of $11 billion, and Neyveli Lignite Corporation, which operates under the Ministry of Coal, planning for 4 gigawatts of solar power worth more than $4 billion.

Major solar manufacturers, such as Trina Solar and JA Solar, have committed to building Indian manufacturing capacity. Many of the top renewable energy utilities, including Engie, EDF Energies Nouvelles and Enel Green Power have acquired Indian firms to boost their presence in the country.

Despite the land grab for projects and partners, “It’s a mixed bag,” said Jasmeet Khurana, associate director of consulting at Bridge to India, a leading solar consulting firm. “These intentions will only materialize if everything falls into place, and that will take several years.”

Some firms are diving in only to pull back once they’re in the water. “They don’t find the pricing and risk-reward ratio suited to their requirements,” said Khurana. Other firms, such as Trina Solar and SoftBank, have shown a “clear intent” to play in the market, he added.

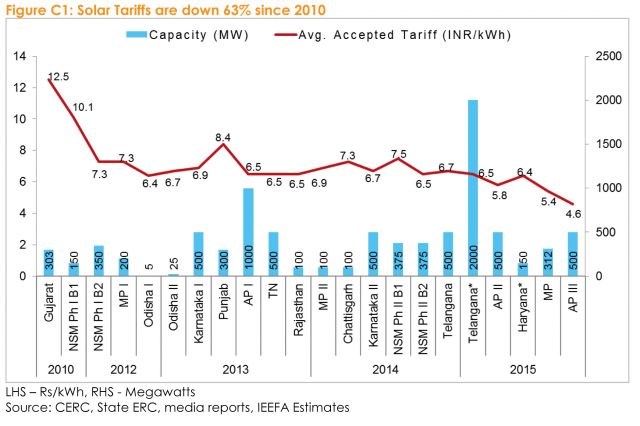

Local solar installers are already balking at low prices that have come as foreign players are flooding the market, according to PV Magazine. The IEEFA report tracked the falling cost of solar, but noted that at Rs 5 per kilowatt-hour, it is still competing in the short term with wholesale costs of other generation that come in at about Rs 3/kWh. Local installers will have to find a way to stay competitive with global firms as prices continue to drop, as they are expected to do.

Prime Minister Modi is pressing ahead with his ambitious cleantech agenda despite some local concerns. He recently reaffirmed to state leaders that they should work proactively to build policy to implement solar and wind projects faster.

Besides political pressure, another driver for distributed solar in India is that it could avoid some of the technical losses that plague the transmission grid. India suffers from 26 percent in technical losses. The energy minister has a goal of cutting losses by 15 percent.

Even if the country can get to 18 percent technical losses by 2022, that is still double the global average and would offset nearly all new gross electricity production that had been added. “There are massive system-wide avoided costs that distributed generation like solar with storage would deliver to India, for both on- and off-grid applications,” the IEEFA report states.

Although there is considerable momentum, there aren’t enough projects on the table for the more than $100 billion in planned investment to be realized, said Khurana. “At this stage, it is difficult to say whether that will happen.”

But Modi is not taking no for an answer, and is pushing for solar support not only at home, but also on the global stage. At the G20 Summit in Turkey this week, he urged other nations to commit $100 billion per year to finance cleantech.