What happens to an office building’s electricity demand when almost everyone who works there is stuck at home?

The coronavirus pandemic has forced broad swaths of the economy to shut down, as state after state forced nonessential businesses to close. The result has been significant drops in electricity demand in big commercial centers like New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area, and forecasts that commercial energy usage across the country will decline by 4.7 percent this year.

But just because a building is almost empty of people doesn’t mean that its energy use drops to nothing. Shutting down key building systems like heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) can lead to unhealthy air or corrosion in boilers and chillers. Emergency lighting and elevators must remain on, as must the servers running the business tasks being carried out by employees at home. Any equipment that was left plugged in when the office closed down will still be using standby power.

Office building energy consumption fell steadily through March and into early April, but it did not fall off a cliff, according to Hatch Data, which monitors 400 million square feet of commercial real estate for more than 250 clients. If anything, it's surprising that the drop-off was not steeper, Ben Mendelson, chief commercial officer and co-founder, said in an interview last week.

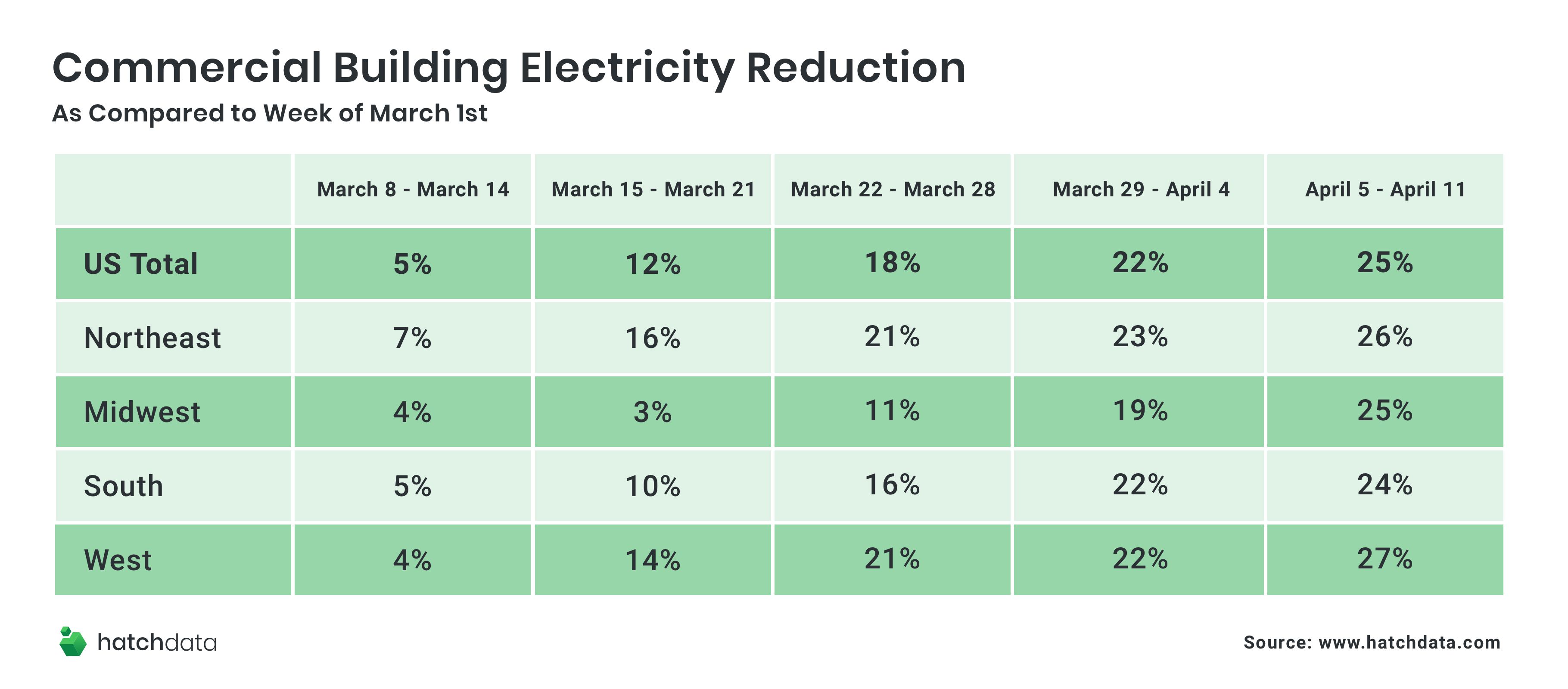

Compared to the first week of March, office building energy consumption fell 5 percent the next week, continued to drop from there, and was 25 percent lower by the first week of April, as the chart below shows.

Hatch believes its data is representative of the country's office building stock as a whole. The San Francisco-based company was formed in January as a carve-out of the energy intelligence services branch of demand response provider EnerNOC, which was acquired by Enel in 2017.

Some slight regional variations show up in the data, with the Northeast's demand falling earlier and faster, and the Midwest's later and more slowly.

That’s largely attributable to the staggered implementation of stay-at-home orders in different states and regions, Mendelson said. With almost the entire country now under restrictions to combat the spread of the coronavirus, “it’s going to continue to come down" from the early April figures.

At the same time, “it was a bit surprising, looking at the data, that these reductions weren’t larger,” Mendelson said — at least at first glance.

The graph below shows one of the office buildings managed by Hatch Data, which has seen energy use decline by an average of 20 percent over the month of March. That includes relatively small reductions in the early weeks, with only the final week seeing weekday working-hours usage falling to what one might consider minimum operating levels.

To understand why, Mendelson pointed to the underlying nature of office building electricity use, which is not nearly as flexible as most casual observers might imagine.

“Just because we’re in this period of reduced occupancy doesn’t mean that buildings are mothballed,” he said. “By and large, buildings are still running, and they’re preparing for re-occupancy to ensure that when people come back to work, they’re coming back to a healthy working environment.”

The easiest load to manage is lighting, Hatch Data CEO and co-founder Zach Robin said. “You can turn it off anywhere [that] it’s not emergency lighting” or would otherwise violate safety codes. But lighting typically accounts for only 15 to 20 percent of a building’s energy use.

HVAC accounts for a far greater portion of energy use, about a third or more for most buildings, and it can’t be shut off completely. “Many of these systems circulate water, and if they’re left off for too long there can be corrosion and other damage,” Robin said. Shutting off air circulation systems air can violate rules for maintaining healthy air quality and endanger the few people who are still coming into the building on a regular basis.

That limits most HVAC energy-saving efforts to reducing run times, adjusting equipment sequencing, reducing static air pressure settings and other nonessential tweaks, Mendelson said. “Certainly, when you’re working with building controls, it’s not a quick fix. You’re working with third parties, with vendors. In this economic climate, it’s important to squeeze every last dollar they can. But that does not come before the health and safety of tenants.”

Then there are the “plug loads,” or the computers, servers, printers and everything that’s plugged into wall sockets. There’s little that building operators can do about those unless they can get the building’s tenants to engage in unplugging all nonessential equipment, Robin said.

Looking at the sample building graphed above, “that’s down to little less than half its load. The other half is probably split in half between plug load and HVAC.”

Hatch Data's software helps customers reconfigure building control systems, invest in efficiency upgrades and take other actions that shave between 15 and 30 percent from their energy bills on average, Robin said. That’s on par with typical efficiency gains driven by companies working in the space such as Carbon Lighthouse, Engie Insight (formerly Ecova) and Centrica Business Solutions, as well as the building management offerings from big equipment vendors like Siemens, Johnson Controls, Honeywell, Trane and Schneider Electric.

But in the past few weeks, customers have been logging in far more often than usual, Mendelson said. That’s particularly true for those buying electricity on competitive energy markets who need to understand how their long-term contracts deal with the unexpected contingency of using far less electricity than predicted.

Those contracts can include “bandwidth” or “material-change” provisions, which allow electricity suppliers to shift customers from locked-in energy prices to the hour-by-hour prices set on wholesale energy markets — and those energy markets are becoming far more volatile with the demand disruptions that are being caused by the coronavirus pandemic.