A few weeks ago, UC-Davis economics professor James Bushnell blogged about the concerns that cap and trade will drive up gas prices in California. In late June, those concerns resulted in a letter from Assemblymember Henry Perea and fifteen other Democrats asking the California Air Resources Board to delay this expansion of the cap-and-trade program to include transportation fuels from January 1, 2015 to January 1, 2018. And a couple weeks ago, ARB Chair Mary Nichols sent a reply explaining why ARB was not going to do that.

Meanwhile, the oil industry and some other groups opposed to fuels in the cap-and-trade program have been making inaccurate statements that the change will cause huge increases in gasoline prices. The ARB and some other supporters of fuels under the cap have responded with their own inaccuracies, saying that including fuels in the program needn’t raise gas prices at all and suggesting that any increase is the fault of oil companies.

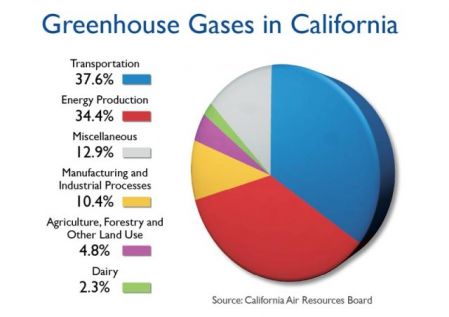

There is a real policy debate here about how and when California should reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, 38 percent of which come from transportation. I share Jim’s view that this is a moment of truth in which California needs to show it will really step up to reduce GHGs. Unfortunately, that debate is being obscured by the spin over how much gas prices will go up when we expand cap and trade on January 1, 2015.

So here’s my attempt at de-spinning (I’m going to focus on gasoline, but the calculations are similar for diesel).

California’s gasoline blend sold at the pump is 90 percent gasoline and 10 percent ethanol, a ratio that is unlikely to change anytime soon. Ethanol counts as zero carbon under cap and trade (long story, but not as silly as it sounds). Pure gasoline emits about 0.009 tons of CO2e (the units of the cap-and-trade allowances) per gallon, so the gasoline blend you put in your car will make the seller responsible for about 0.008 (90 percent of 0.009) allowances per gallon.

The current price of an allowance is slightly less than $12 per ton, and the futures market predicts it will be about the same on January 1, 2015. Our own analysis finds that the price of allowances will most likely remain in the $12 to $15 range out to 2020.[1] There is a small, but real, risk that allowance prices could go much higher a few years out, which we discuss in detail in our report. But if you want to know what gasoline price “shock” will hit consumers in January when gasoline comes under the cap-and-trade program, the relevant allowance price is about $12 per ton. That will increase the marginal cost of selling a gallon of gasoline by about 9 cents to 10 cents per gallon on January 1.

A large body of literature in the field of economics has examined what happens to gasoline prices when the marginal cost of selling gas increases, looking at changes in the price of crude oil and changes in gas taxes. The answer: those increases are passed through one-for-one to consumers, generally in a matter of days, or maybe a week or two.

That’s why the almost certain outcome is that within a few days after January 1, 2015, the cap-and-trade program will cause the price of gasoline in California to increase by 9 cents to 10 cents, a margin that is lower than the drop in gas prices that has occurred over the last few weeks.

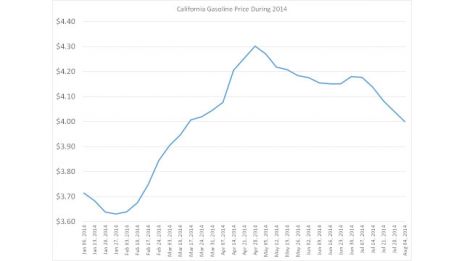

FIGURE: California Gasoline Pricing During 2014

Source: Energy Information Administration

Average California gas prices so far this year

What’s that you say? You didn’t notice the drop? I’m not surprised. With oil price fluctuations regularly pushing gasoline up or down 25 cents or more, an extra 10 cents one way or the other doesn’t catch the attention of most consumers.

Before I move on to confront some of the spin, let’s consider that price increase in context. A 10-cent increase equates to about 2.5 percent. Here are some things you could do to fully offset that additional cost:

- Drive 70 mph instead of 72 mph on the freeway. That difference would improve your fuel economy by about 2.5 percent. The savings are much larger if you actually drive the speed limit.

- Buy a car that gets 31 mpg instead of 30 mpg. That will get you more than a 3 percent savings in fuel cost, more than offsetting the price increase.

- Keep your tires properly inflated. The Department of Energy estimates that underinflated tires waste about 0.3 percent of gasoline for every 1 psi drop in pressure.

Instead of this simple reality, we are hearing misinformation coming from both sides.

The Western States Petroleum Association says at every opportunity that cap and trade will raise the price of gasoline by 16 cents to 76 cents per gallon. Huh? These ranges don’t even include the most likely effect of 10 cents. The industry got to these much-scarier ranges in two ways, both of which are -- to be charitable -- not based on the currently available information.

First, they took a 2010 ARB study (from before the final details of the program were even set) that predicted a 4 percent to 19 percent price increase back when gas prices were in the $3 range and just slapped it onto the current price of $4. That doesn’t make any sense, because the cost of allowances doesn’t scale up and down with the price of gasoline. But in any case, the range was based on a range of possible allowance prices from a 2010 analysis. We know a lot more now than we knew in 2010. For instance, we now know the current market price of allowances and the market’s prediction for the January price. Those allowance prices imply that gasoline prices will rise by 9 cents to 10 cents, below the bottom of the very wide range the oil industry asserts is possible.

Second, WSPA took a prediction from their own consultants’ 2012 report, which argued that allowances would cost $14 to $70 and (having performed the calculation slightly incorrectly) concluded that this would cause the emissions costs from gasoline to be 14 cents to 69 cents per gallon.[2] More recent information suggests the best forecast for January is below this range, so the oil industry is just choosing to ignore more recent information.

On August 1, the oil industry doubled down on their assertions in a letter to ARB. While making some valid points about ARB’s misguided claims (which I’ll discuss below), WSPA states that ARB’s 2010 numbers must be the best estimates out there because ARB hasn’t put out a new estimate. That seems somewhat disingenuous, given that the oil industry is as familiar as anyone with the market price of allowances. They can certainly do the calculation I’ve carried out above.[3]

The oil industry might respond that the high end of this range could conceivably happen years from now if no further changes to the program are made. That’s true -- as our report explains -- but these figures are being used to argue for a three-year delay in fuels under the cap, often using the WSPA range to discuss the price shock that might otherwise occur in January 2015. In reality, the “shock’’ on January 1 will likely be an increase of about 10 cents.

The oil industry’s numbers are eye-catching -- much more so than the boringly realistic 10-cents-a-gallon impact estimate -- and they are getting traction. Media reports of expected increases include 15 cents to 40 cents, 17 cents or higher, 40 cents, 15 cents or more and 15 cents. A few stories repeat claims that cap and trade could cause gas prices to spike by more than a dollar, though I haven’t seen that claim attributed or justified. Even the letter from the assemblymembers to ARB says of the immediate price jump at the pump on January 1, 2015: “an increase of about 15 cents is likely and a much larger jump is possible.”

ARB officials and (others supporting the policy such as Tom Steyer) seem to have decided that counter-spin is a better strategy than straight talk. They have repeatedly suggested that if gas prices rise in January, ARB policy would not be the cause, saying that cap and trade just requires sellers to turn in allowances; whether they choose to pass along that cost to consumers is their decision, not ARB’s.

Really?

Every economic analysis of cap and trade I have ever seen -- whether left, right or center politically (and including ARB’s own analysis) -- recognizes that it will raise the cost of selling gasoline and that this increase will be passed along to consumers. That isn’t due to some conspiracy. It’s how markets work; when the marginal cost of selling a good goes up, firms raise their prices. The cap-and-trade program will likely cause gas prices to go up in January 2015 by about 10 cents per gallon.

An ARB spokesperson has also suggested that these costs somehow won’t or shouldn’t be passed along because oil companies have been buying allowances since 2012 and already have a lot of them.

What?

That’s like saying you paid for your house long ago, so now you should give it away for free when you move. In reality, every allowance a fuel dealer uses to cover its compliance obligation from selling gasoline will be an allowance it can’t sell in the marketplace. That’s a real cost.

In the letter to Assemblymember Perea and his colleagues, as well as in other statements, ARB argues that any price impact from cap and trade should occur gradually, not with a sudden jump on January 1. But the cost effect of fuels under cap and trade will go from zero on December 31, 2014 to 10 cents on January 1, 2015. Just like an increase in crude oil prices or raising a gas tax, the empirical evidence is that this will show up at the pump within days.

The bottom line: Like Bushnell, I strongly support bringing fuels under cap and trade on January 1, 2015. That’s been the plan for many years, and the current arguments for delay contain no new information. Robust debate is valuable, but that debate is undermined when the public is told either that this change won’t (or shouldn’t) cost them anything or that the cost will be many times higher than the most reasonable estimates.

One final note about public opinion: Many of the newspaper articles on the price increase and many of the advocates for delay are citing a poll conducted by the Public Policy Institute of California. They quote the PPIC report as saying “A large majority of Californians (76 percent) favor this requirement [including transportation fuels in cap and trade], but support declines to 39 percent if the result is higher prices at the pump.” Is that informative? When you look at the actual survey question (page 31, question 30), I’d say it’s pretty useless. The question asks if you favor requiring oil companies to “produce transportation fuels with lower emissions?” and then asks, “Do you still favor this state law if it means an increase in gasoline prices at the pump?” There is no specific increase mentioned; that’s left up to the imagination of the person answering. I bet if they asked about a 1-cent increase, there would have been almost no change, and if it asked about a 1-dollar increase, support would plummet. Too bad they didn’t ask about a 10-cent increase. That would have been interesting. But it's difficult to interpret the results of the question that was actually asked.

[1] The California Legislative Analyst’s Office sent a letter to Assemblymember Perea last week that called our study the most credible of the studies they reviewed. They used our estimates to say that gas prices would likely go up by 13 cents to 20 cents by 2020. They did not mention that the same reasoning implies the impact in 2015 will be about 9 cents to 10 cents per gallon, but that is what their analysis also implies.

[2] Actually, the report states this range for the year 2020, which is three years after the proposed delay of implementing fuels under the cap.

[3] Some in the oil industry continue to argue that transportation fuels under cap and trade will hurt sellers (in reality, it won’t, because the cost will be fully passed through) and that sellers should receive some free allowances to cover this additional burden. Free-allowance allocation would just be equivalent to a cash gift to gasoline distributors; for the marginal cost reasons explained, they would still raise gas prices. (In fact, EU policymakers tried this and were “shocked’’ to see that the companies getting free EU-ETS allowances still raised their prices.)

***

Severin Borenstein is E.T. Grether Professor of Business Administration and Public Policy at the Haas School of Business and Co-Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He is also Director of the University of California Energy Institute. His research focuses on business competition, strategy, and regulation. He has published extensively on the airline industry, the oil and gasoline industries, and electricity markets. Since 2012, he has served of the Emissions Market Assessment Committee that advises the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases.

Reprinted with permission. Original column appears here.