The home hot water heater is hardly the cool kid in the appliance schoolyard. It doesn't receive daily human interaction. It mostly dwells in the basement. There is no former Apple designer bringing us a new, sexy water heater.

But that doesn't mean the appliance is completely forgotten. There is a tussle brewing in Washington over the second-largest energy hog in the house. The lowly hot water heater has long been part of load control programs run by electric utilities. Some hot water heaters also receive significant rebates as part of utility energy-efficiency programs. Now the two programs are potentially pitted against each other because of proposed energy conservation standards for residential hot water heaters put forth by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Demand response and energy efficiency are often seen as two peas in a pod. While efficiency can drive down overall energy use, even more kilowatts can be shed when the grid needs it most.

The point of contention is that large water heaters, over 55 gallons, will be required to have an energy factor of at least 2.057, a figure that’s double the efficiency of a high-efficiency electric storage heater. The new standard could only be met with heat-pump water heaters, instead of the classic electric resistance water heaters.

The problem is that heat-pump water heaters, while far more efficient, are essentially no good for demand response. The heat-pump water heaters are far more efficient because they move heat from one place to another (i.e., from the room to the water), instead of generating it directly.

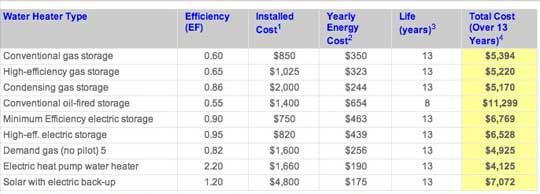

For some of the larger appliances, including hot water heaters, there is also a natural gas option, which is inherently more efficient than electric, because the energy source does not have to be turned into electricity and then transported with losses to the home. About 60 percent of water heaters are already powered by natural gas, and there is a move afoot to introduce more gas clothes dryers to the U.S. market.

*ACEEE

“To meet the efficiency standards, they’ve got to run low and slow,” Jay Morrison, VP of regulatory issues for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA), said of the heat pump technology. The "low and slow" is great for efficiency, but “it would not be a good tool” for demand response, he added. NRECA joined with PJM Interconnection, the American Public Power Association, the Edison Electric Institute and the Steffes Corporation to support a modification of the new rule.

Currently, there is a fix in place that would allow for one-year waivers for manufacturers making large capacity water heaters that will be used for specific demand response programs. But getting the waiver will be difficult every single year given how many demand response programs there are.

“There is absolutely no way I can think of that I can bribe a manufacturer to gear up to manufacture a product for one year,” Harvey Sachs, representative for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), said at a public hearing on the issue. The ACEEE supports more stringent energy-efficiency standards, but not at the cost of demand response.

Amongst NRECA members, more than 220 utilities have demand response programs with water heaters, and another 100 are in the planning phase for similar programs. Thirty-five states have utilities (of all sizes) with water heater load control programs. The utility organizations aren’t unequivocally against heat-pump water heaters, but they are looking for a clearer waiver with a longer timeframe, such as five years.

Any final decision will not upend the entire market. Heat pump technology only claims about 15 percent of the total water heater market, according to Morrison. Many households also don’t have a unit over 55 gallons. “We have a lot of members that are encouraging heat pump water heaters as well,” added Morrison. But for demand response programs that do leverage water heaters, the large ones are seen as particularly valuable.

Leveraging water heaters is not just some old-fashioned load control program -- although some programs are. The Northwest Demonstration Project, for instance, is using transactive controls to communicate with residential hot water heaters to help balance load from wind resources.

Water heaters aren’t the only household appliance that could be tapped for demand response. Heating and cooling has the largest potential, but everything from refrigerator compressors to dishwashers could theoretically be shifted to run when energy costs are lower if they could receive utility signals.

The problem -- and it’s a good one to have -- is that many new appliances that would have the ability to communicate with a utility program are far more efficient than their predecessors and therefore have less load that can be shed during times of peak energy use.

No matter the decision, utilities will continue to tap hot water heaters for demand response. Despite efficiency gains that have been made in the area of air conditioning, the number of homes with AC continues to climb in the U.S., creating even more energy peaks, but also increased opportunity for demand response.

The new standards for hot water heaters will go into place in April 2015.