GTM's tenth annual Solar Summit took place this week in exciting, frustrating and volatile times for the industry. Shayle Kann, senior vice president at GTM Research, kicked off the event by confronting the difficult realities of the solar industry today. He also gave some strong reasons for hope in this still maturing marketplace.

Here, in Part 1 of the presentation, Kann looks back and at the next year or two. In Part 2, which we'll cover next week, he forecast the ways this market can reach thousands of gigawatts installed and trillions of dollars invested. (The video archive of the event is available to GTM Squared members.)

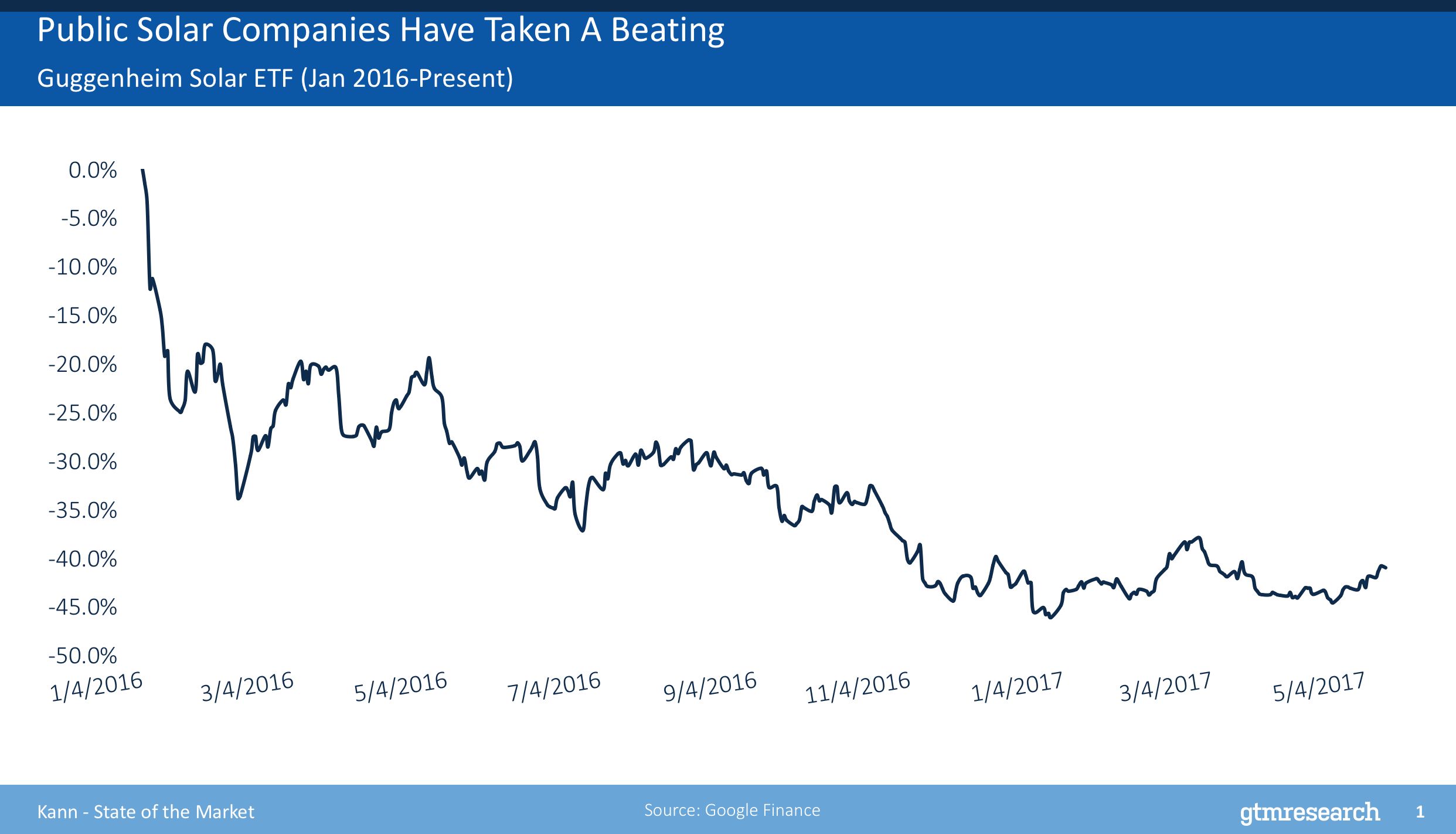

"If we look at just an aggregate of solar and pure-play solar stocks, it's down about 40 percent since the beginning of 2016," said Kann. "It improved a little bit in the past few weeks, but not a whole lot. Of course, stock prices are not always the greatest indicator of the whole market, but in this case, many companies have had a tough year, year and a half.

"In particular, it's been hard for module manufacturers," he continued. "And this has been true especially in the second half of 2016 and today."

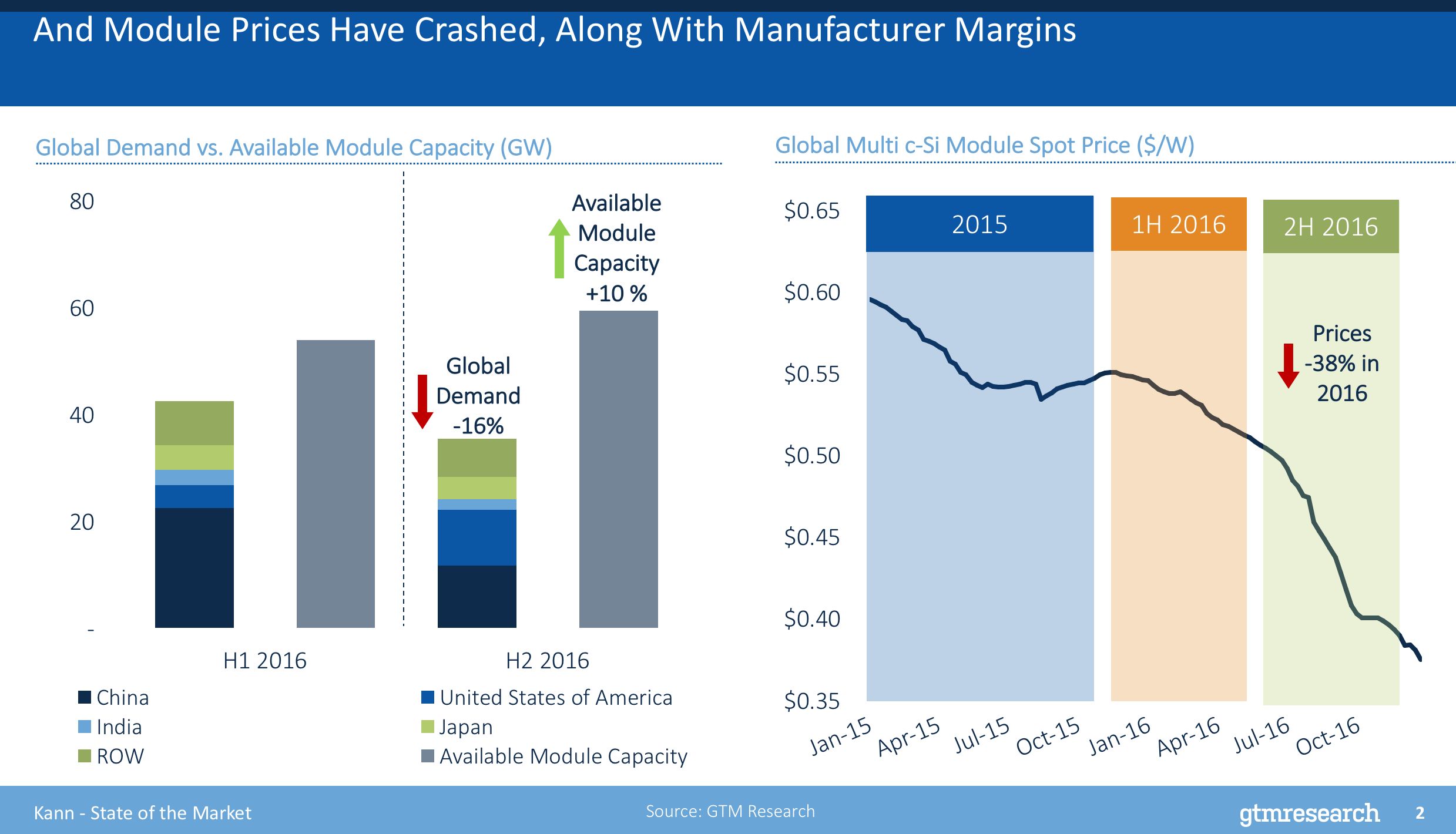

According to Kann, "The change between the first half and second half of last year was pretty stark, and it went in two different ways. First of all, between the first half and the second half of last year, the global demand for solar fell by 16 percent. This is despite the fact that we are having a banner year for solar overall.

"But China pulled back its entire program at the end of the first half of the year. There was a big contraction in the Chinese market in the second half of the year, and despite the fact that we saw a lot of growth in the U.S. and India, and some other markets, the global market shrank in that six-month period.

"As has been the case many times in solar, and this is a cycle we tend to repeat -- and module manufacturers and manufacturers did not got the message in time -- they continued to expand capacity. What happens when you have a shrinking market and you grow capacity at that the same time? You get thrown into oversupply. And that's what happened in the second half of 2016. And the result of that, of course, as is generally the case in oversupply situations, is that prices crash. They ended up falling almost 40 percent just over the course of 2016, most of it in the second half.

"We remain in an oversupply cycle for panel manufacturing, and manufacturers have suffered as a result and margins have compressed. They've had to figure out how to survive through the downturn. Now normally, when you have oversupply in panel manufacturing, that is going to be bad for the manufacturers. It's good for the downstream. It's good for anybody who is buying panels, anybody who is developing projects. Indeed, I think that was true for many companies in 2016 through to today. We have a lot developers that have benefited from that. But it's not universally true."

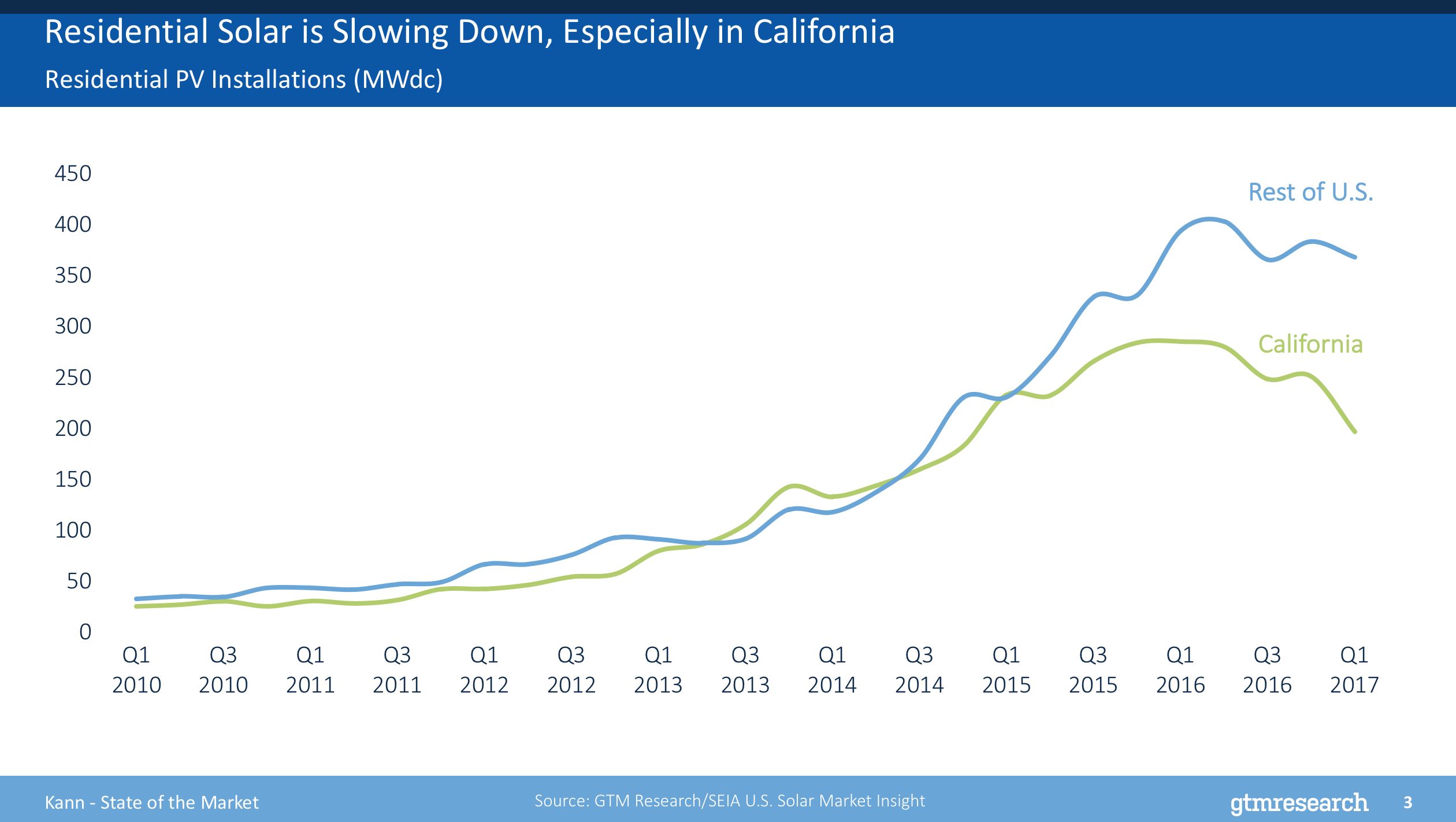

In the U.S. in particular, there's been a simultaneous challenge in the market specific to the residential solar, Kann said.

"The residential market in the U.S. was booming for years," he said. "From 2012 to 2015, four years in a row, the residential solar market grew by over 50 percent a year. And then in 2016, it started to slow down. We saw 19 percent growth last year. And all indications are that 2017 is basically going to be flat overall for residential solar.

"California is a big part of the issue. Not only is the state going to be transitioning to its second-generation of net metering and switching to time-of-use rates, but the state also had to cope with unprecedented rains in the first quarter of this year. The rain made it basically impossible for many installers to get up on roofs. And while California's residential solar market saw a downturn over the winter, growth in the rest of the country went flat.

"This...has been hardest on the largest residential solar companies -- with one little exception: Sunrun," said Kann. CEO Lynn Jurich, who also spoke at the Solar Summit yesterday, said her company delivered 20 percent growth in the first quarter of 2017, while new residential solar capacity overall dropped by 11 percent from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of this year.

The combination of an oversupply for upstream companies and slow growth in the U.S. residential market ended up producing "a lot of negative results," said Kann.

"There have been bankruptcies from SunEdison last year, to Sungevity to OneRoof to SolarWorld. It's been a rough time in the public eye for solar," he said. "And yet, I think we are going to have to take a small step backward...to recognize the milestones that the solar market -- both in the U.S. and abroad -- has simultaneously hit despite some of the turmoil."

"We are at a really amazing point in the history of the solar market, and when we look back at this time 10, 20, 30 years from now, this is going to be a pivotal moment in solar becoming mainstream."

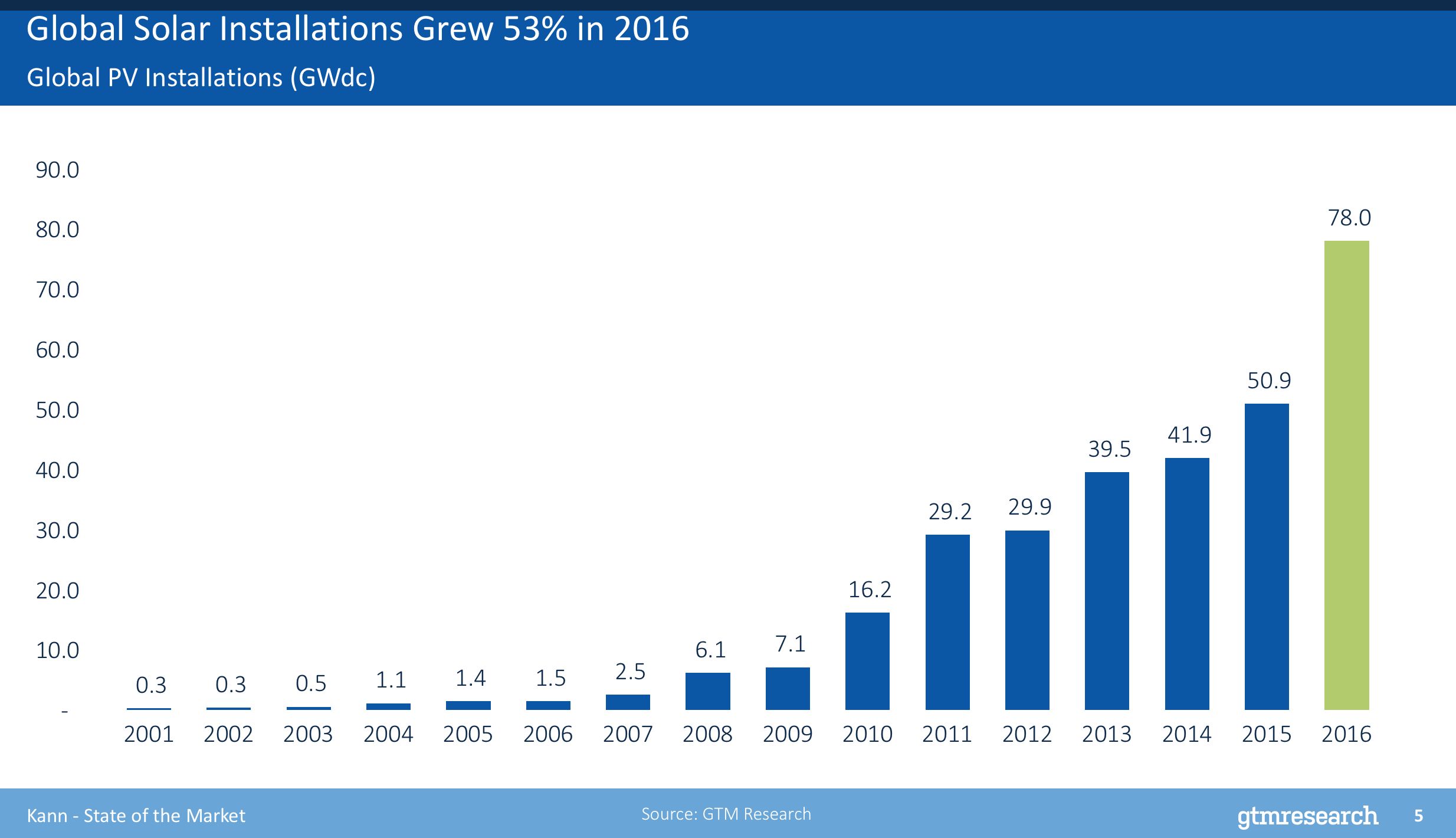

On a more positive note, Kann noted that the global solar market grew by 50 percent overall. "That's huge growth globally -- that's 78 gigawatts of solar, 10 times the amount that we installed in 2009," he said.

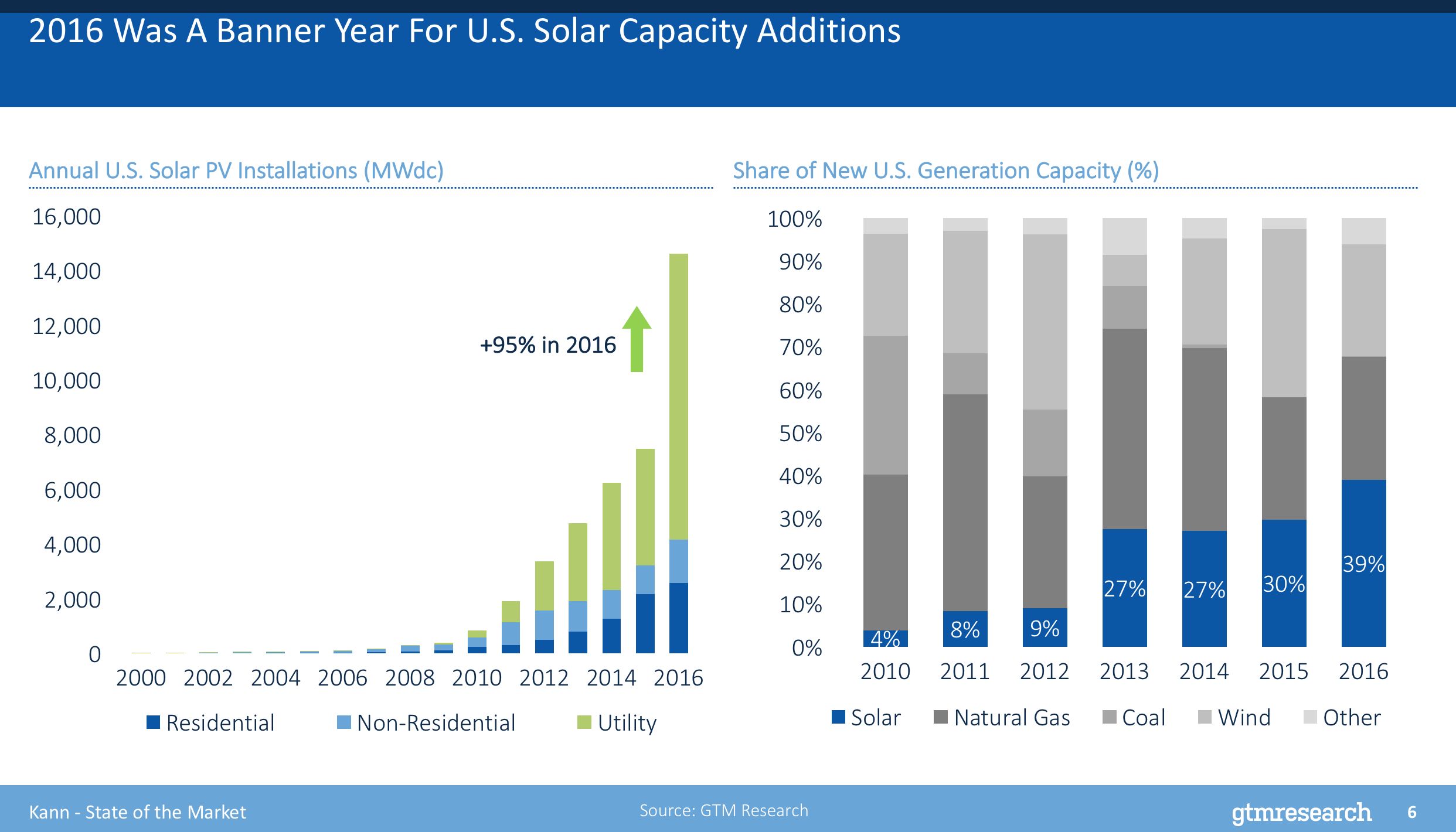

The U.S. installed 14.5 gigawatts last year, up 95 percent over 2015. So the market basically doubled in this country in the last year.

And for the first time ever, solar was the single largest source of new generating capacity in the U.S. "We added more solar to the grid in this country than any other individual resource, more than natural gas, more than coal, more than nuclear, more than had ever happened before," said Kann.

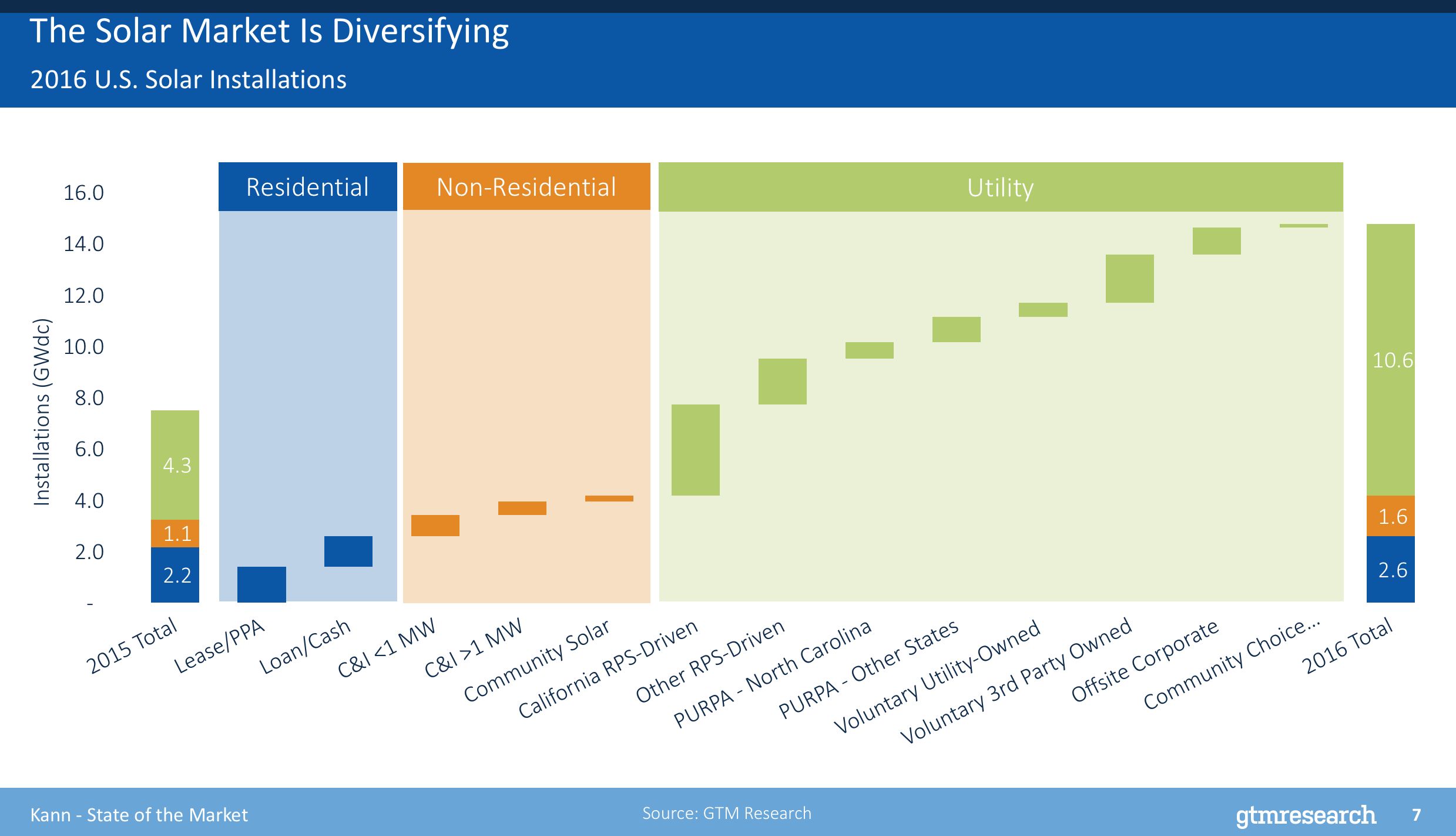

In addition to this massive growth within the U.S., Kann said another important development is that the sources of demand for solar are diversified. He explains:

"So the way that we got to 14.5 gigawatts installed last year is not by just throwing a bunch solar at a single type of market, but instead by opening up new avenues in solar, for the solar economics to work. So how did we do that?

"We add residential solar that was installed both through a third-party ownership model and directly owned by customers through a cash purchase or lease. We have a commercial market, non-residential market, that had actually a fair bit of smaller commercial projects, as well as larger commercial projects. A community solar market emerged. We have RPS-driven demand for utility-scale solar in California and other states. In addition to that, we have new PURPA mechanisms, which are performing across a bunch of states, and voluntary utility procurement, just because the economics work. We have the corporates emerging as a new source of procurement."

Kann's point: This is a diversifying market. If you looked at the chart below just two years earlier, in 2014, there would have only been a couple of segments.

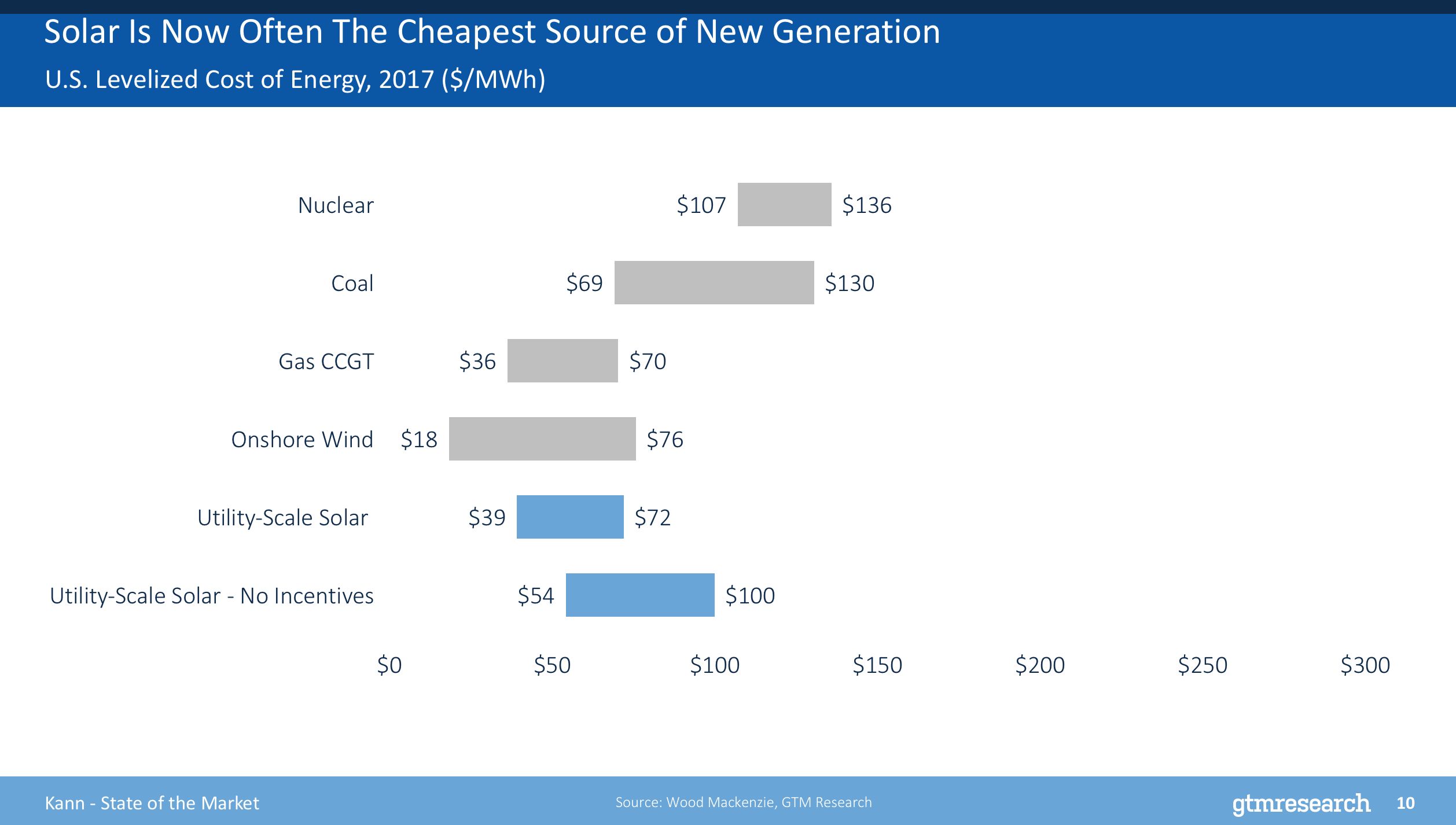

The core point to make here is that there's been a dramatic transformation in solar economics, said Kann. He explained: "Back in 2010, if you wanted to build solar, first of all, it was a new market, with a wide range of pricing, even within a single market -- projects had far different pricing. And if you wanted to make the economics work, you needed a federal incentive, you needed the Investment Tax Credit. But that really wasn't sufficient if you wanted to compete.

"And so the way that we built solar, back in the beginning of this decade, was by stacking incentives. You needed the federal incentive and then you needed something that was state-run. That is, generally speaking, no longer true.

"Today, the cost of solar, if even just taking the ITC into account, is more highly competitive throughout most of the country than basically any other resource. The exception to this is places that have really high wind resources.

"Solar is often now the cheapest new source of generation. And in fact that is becoming true even if you don't take the ITC into account. If all you care about is getting the cheapest kilowatt-hours from any source of generation -- solar is going to win."

He continued:

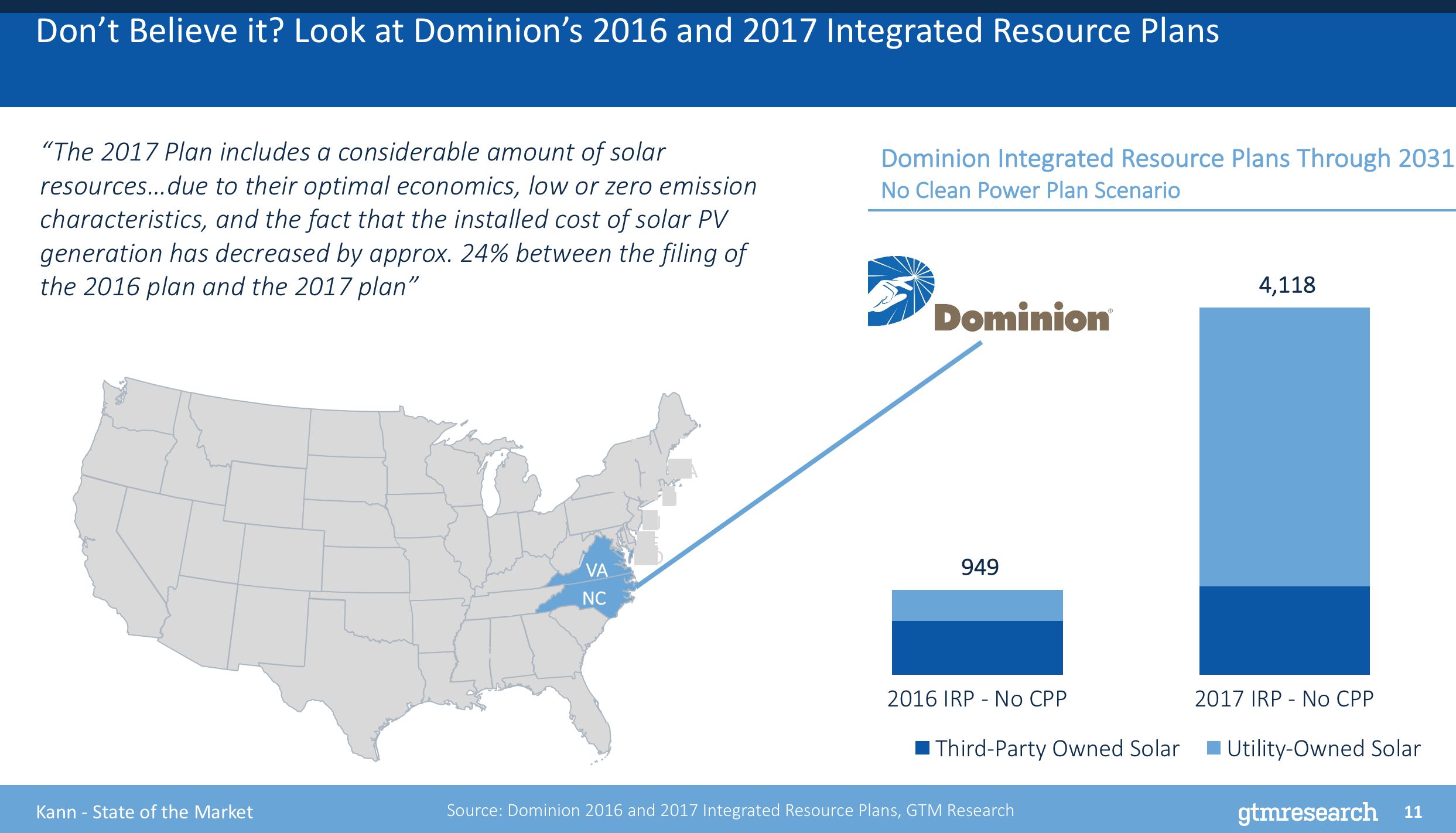

"There are lots of ways you can look for proof points to prove that solar is the cheapest source. Here's one example: Dominion. Dominion is a utility based in Virginia and North Carolina. And Dominion submits an Integrated Resource Plan every year to its regulators. In that Integrated Resource Plan, what Dominion and most other utilities are doing is they're basically running a model to determine, given the resource needs and prospective costs in areas of generation, what the least-cost, best-fit resources are going to be in that territory.

"If you look at the 2016 Integrated Resource Plan, they were already planning to build out a bunch of solar in their territory in the next 15 years or so. But just a couple of weeks ago, they submitted their 2017 IRP, just one year later, running similar models, and the amount of solar more than quadrupled. They now expect in a no-Clean-Power-Plan scenario to build mostly solar, more than any other resource by a long shot -- over 4 gigawatts just by 2031. If we extend it out to 2042, which is how far out the IRP ultimately goes, it becomes more like 5 gigawatts.

"And here's what they said about it in the IRP. Basically, they explained that they added so much more solar into that plan due to the optimal economics, and importantly, the fact that the cost of solar, from their perspective, fell 24 percent between the time that they filed the 2016 IRP and the time that they reviewed the analysis for the 2017 IRP."

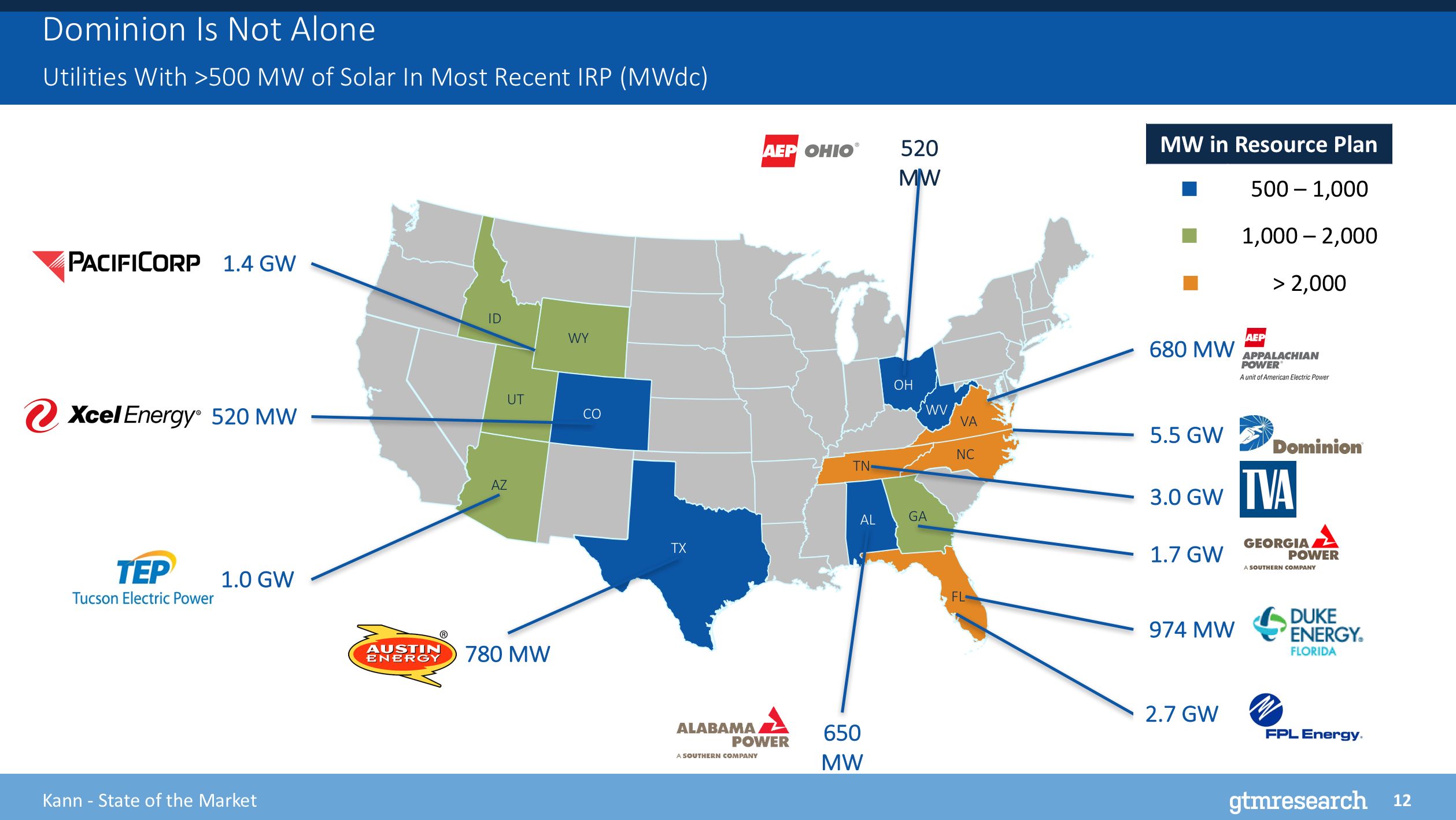

"This is what happens when you get these drastic cost reductions for solar," said Kann. "It has a real, meaningful impact on solar's competitiveness with the other sources of generation. And lest you think that Dominion is alone in this, there are a dozen utilities planning in the same vein."

"In two of the most recent Integrated Resource Plans, they have suggested that they should build at least half a gigawatt of solar in their territory," he said. "Just these 12 utilities could nearly double the size of the cumulative utility-scale solar market. This is 12 utilities out of 3,000 in the U.S. -- so, this is a very real transformation."

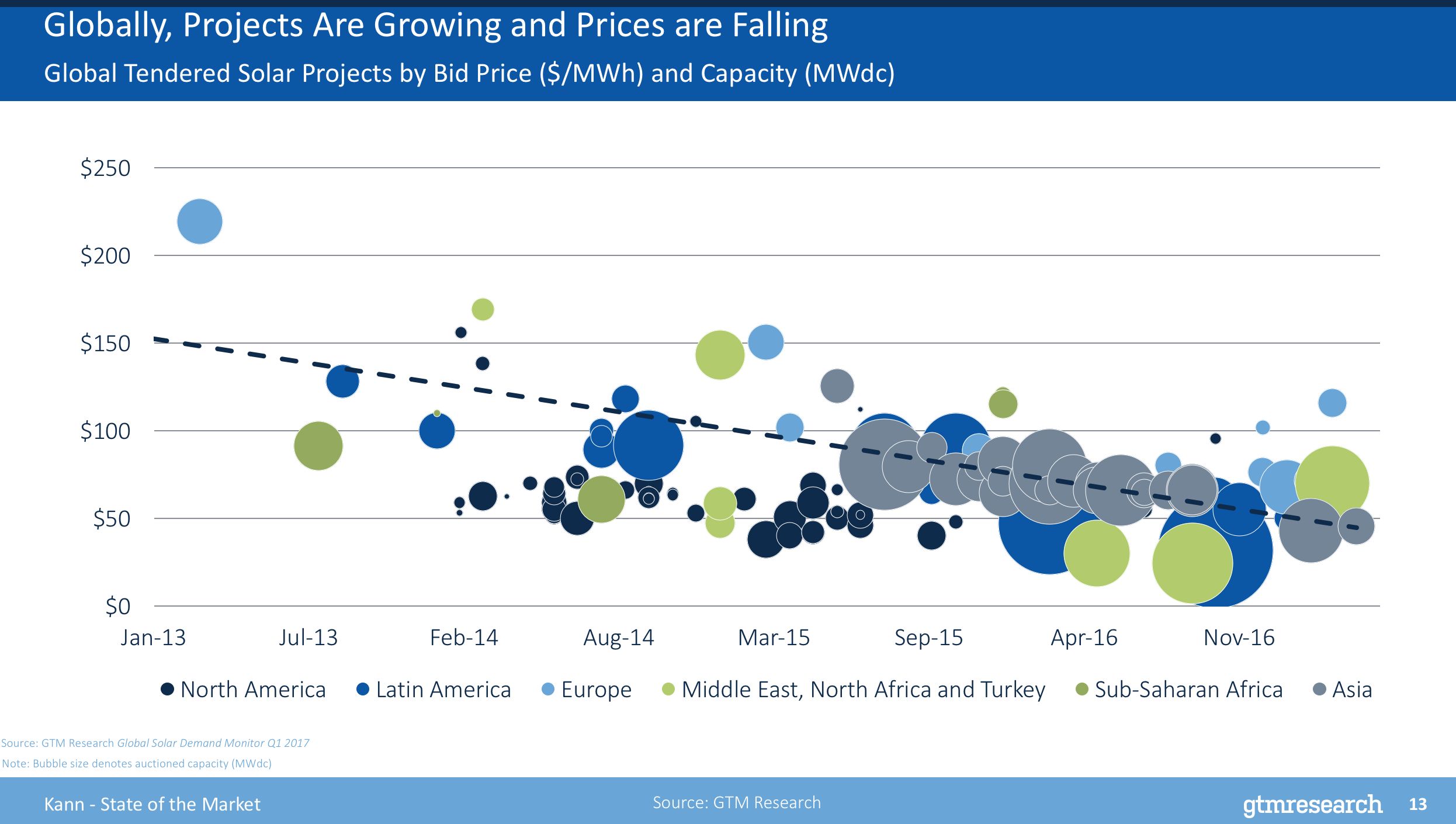

This isn't just a U.S. phenomenon. It's a global phenomenon as well.

Average PPA prices globally are now below 5 cents per kilowatt-hour, according to GTM Research. Plus, basically all of these markets are unsubsidized, so there's no access fee in most of these places -- it's just pure solar prices.

"There's a race for the next record for lowest power-purchase agreement price that keeps happening," Kann said. "We'll get probably the lowest one again in the next couple of months. We have a sub-$30 megawatt-hour price in the U.A.E. We've got another one at about $30 in Mexico. In India, we're down to about $40 a megawatt-hour. India historically has been a much more expensive market for solar, so these projects are real. This is a notable change."

"Again, the point here is not that these individual projects are so cheap; it's that broadly speaking, this is the pricing for big utility-scale solar projects in most of the world."

These ongoing cost declines make solar competitive with, and often times better than, any other source of generation from an economic perspective. The result is that countries all over the world are introducing tender processes, or auctions, or something where they compare competitive pricing from solar values. "We now have some form of auction or tender scheme in over 16 countries either already in place or planned," Kann said.

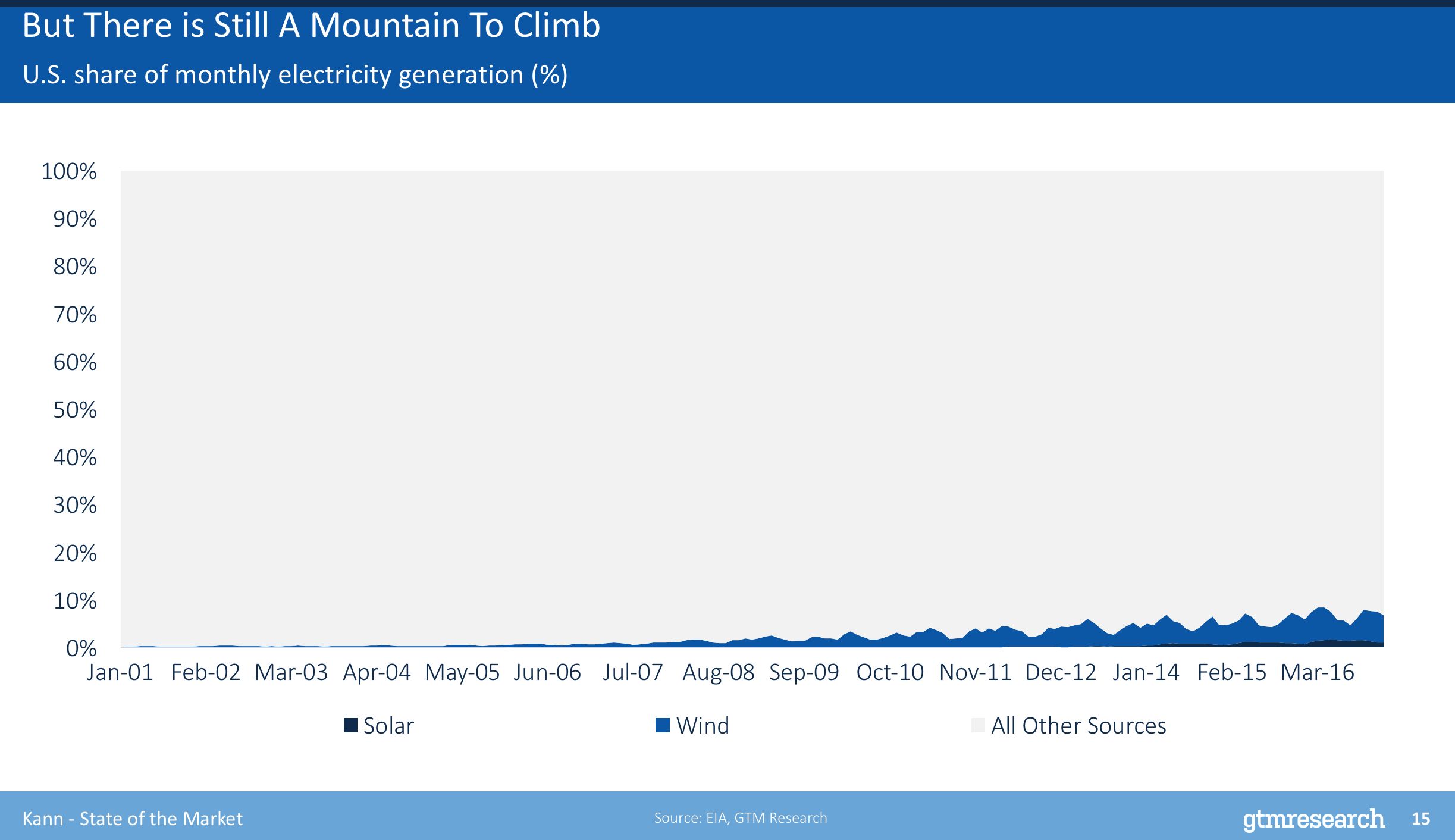

But despite all of this growth, "We have a huge mountain to climb for solar to become a meaningful chunk of electricity both in the U.S. and in the rest of the world," he said. "Right now solar accounts for about 2 percent of electricity generation in this country, and that's actually roughly the same globally. So, we're growing a lot, but from a small base, and we're bleeding into a gigantic market for power generation."

He concluded: "There's a lot to be done."

Read about Part 2 of Shayle Kann's State of Solar presentation on Monday.