The meteoric rise of lithium-ion batteries in the transport and IT sectors has been spurred by demand for technologies that reduce carbon emissions and decrease energy use. While this sounds like a win for everyone, there’s a darker side that could alter the perceptions of ethically minded consumers and create significant risks for brands.

If you look at the production of cobalt and lithium used in these batteries, a stark picture emerges of an industry exposed to issues such as child labor, modern slavery, and the undermining of land and water rights.

Demand for these raw materials is set to grow significantly. Verisk Maplecroft’s sister company, Wood Mackenzie, suggests lithium demand will double to around 380 LCE kt (lithium carbonate equivalent 1,000 metric tons) before 2024, mainly due to an expansion in the production of electric vehicles.

Therefore, IT and auto companies need to be aware of the risks of sourcing from key cobalt and lithium-producing countries, such as Argentina and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. If they’re not, they may face significant reputational damage from association with human rights violations and, in extreme cases, regulatory penalties from the slew of emerging legislative measures addressing supply chain issues.

Traceability of cobalt from DR Congo is a key challenge

Over 50 percent of the world’s cobalt is currently produced in DR Congo, with the copper belt in the southern Katanga region accounting for almost half of the world’s reserves at 3.4 million metric tons. Although much of this is produced at large-scale industrial mines, the Congolese government reports that around 20 percent of cobalt exports from the country originate in artisanal mines, a majority of which are unregulated and operate illegally.

Shockingly, 40,000 children are estimated to be employed in artisanal mines in southern DR Congo, including in cobalt extraction. Verisk Maplecroft’s cobalt risk assessment -- part of its commodity risk service -- reveals that human rights abuses are widespread in the sector and can occur within both industrial and artisanal mines. According to the research, the country is rated "extreme risk" for child labor, modern slavery, trafficking and occupational health and safety.

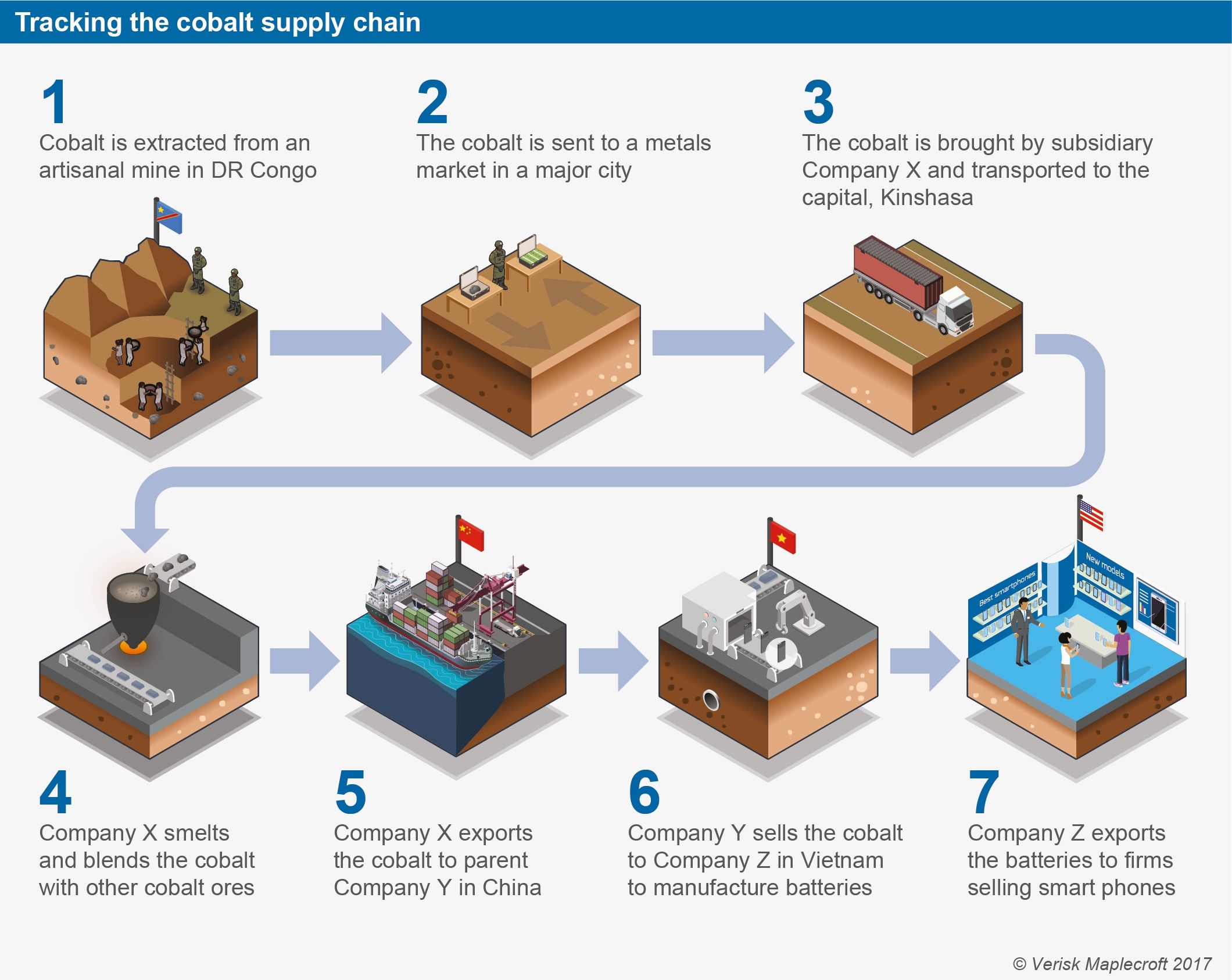

One of the key challenges for companies is traceability. Once mined, the mineral traverses a complex supply chain that can include the smelting together of cobalt extracted from both artisanal and industrial mines, which is then transported overseas. China, which produces over 40 percent of the world’s refined cobalt, imports over 75 percent of the raw cobalt it uses from DR Congo. The refined metal is sold on to battery manufacturers, which then sell their products to multinational brands.

No laws or widely acknowledged partnerships or initiatives exist to support increased traceability for cobalt mined in DR Congo -- unlike those in place for 3TG (tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold) conflict minerals. It is this lack of visibility down the supply chain that leaves companies exposed to the breadth of social and environmental issues linked to cobalt production.

Environmental risks set to rise in the lithium triangle

Risks within the production of the new wave of batteries are not, however, confined to labor rights or illegality. Ironically, the environmentally friendly image of electric cars and green technology belies the environmental impacts associated with lithium mining in South America.

Following the scrapping of mining export taxes by President Mauricio Macri, Argentina has emerged as the pre-eminent producer in South America’s "lithium triangle," which also encompasses Bolivia and Chile. The resulting surge in investor interest in Argentina could see investment in the sector top $20 billion between now and 2025. However, as investment grows, so does the number of legal challenges from indigenous and rural communities fighting against the industry’s demand for water and land.

According to Verisk Maplecroft’s water stress index, the lithium-rich Puna highland desert of Salta and Jujuy is classified as "extreme risk." Conflict between mine operators and local populations over water rights have led to 33 indigenous communities from Salta and Jujuy filing legal challenges against lithium operations in Laguna Guayatayoc and Salinas Grandes.

A potential ruling in favor of the communities by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights is unlikely to halt operations, but local demonstrations against the projects might create continuity issues if they escalate to the extent of protests that we see in Peru.

Ultimately, environmental issues affecting lithium production in South America pose less of a risk to business than the extreme environment of DR Congo, and they are unlikely to spur the kind of regulatory response that human rights violations in the supply chain have prompted. However, companies found to be sourcing from mines perceived to encroach on local populations’ access to water, or indeed the rights of indigenous peoples, may face a reputational cost.

Given the high-profile use of lithium-ion batteries in emerging technologies, scrutiny of the production processes behind them will undoubtedly rise, especially for brands targeted at environmentally and socially conscious consumers. A better understanding of the social and environmental issues associated with their production in key countries might just help businesses avoid legal or reputational challenges further down the line.

***

Stefan Sabo-Walsh is director of commodities research at Verisk Maplecroft. Greentech Media is owned by Wood Mackenzie, a Verisk company.