The Grain Belt Express, one of the biggest U.S. proposed transmission projects designed to carry Midwest wind power to eastern markets, is one step closer to completion after winning key court and policy battles in Missouri.

On Tuesday, a Missouri state appeals court ruling upheld a decision by state utility regulators last year allowing Chicago-based renewable energy developer Invenergy to acquire the 780-mile, $2.3 billion project from its founder, Clean Line Energy.

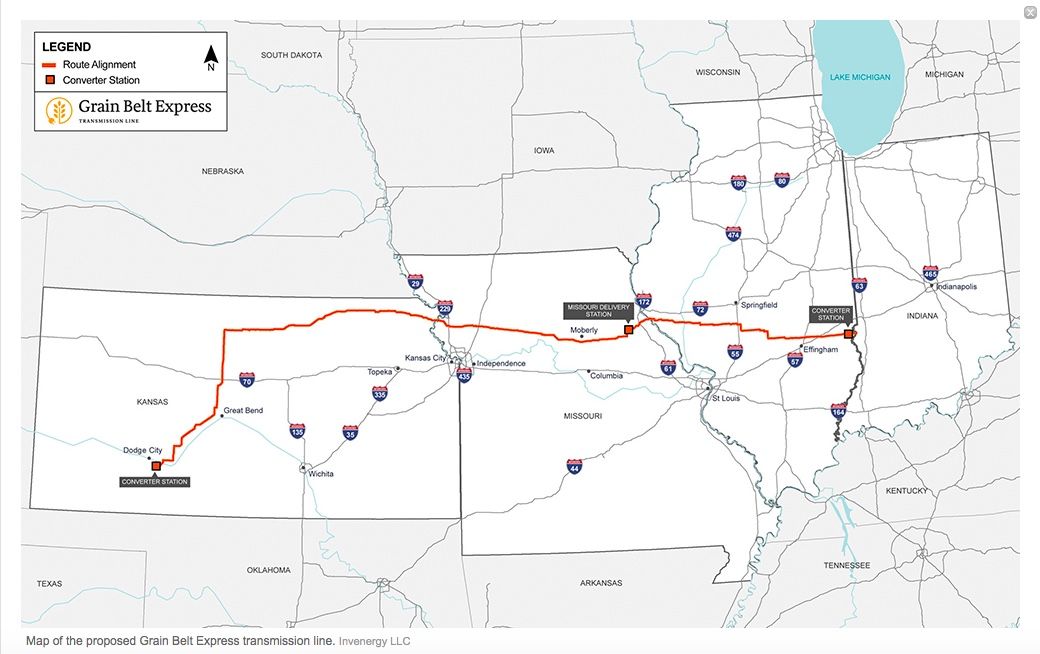

It’s the latest victory for a project that will carry up to 4,000 megawatts of wind power in western Kansas to its endpoint in Indiana, and from there to the 11-state market of grid operator PJM. In May, the Missouri legislature failed to advance a bill that would have barred Invenergy from using eminent domain power.

Invenergy, which announced plans to acquire the project in late 2018 after Clean Line Energy closed its doors, is building wind farms across the Midwest, including west Kansas projects hungry for markets. Invenergy spokesperson Beth Conley told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that the project would bring $500 million in private investment and 1,500 construction jobs to the state.

But Grain Belt Express has faced the same type of opposition from landowners and state and county governments that have plagued most of the large-scale transmission projects across the country aiming to connect far-off wind and solar power projects to energy markets.

After initially being denied by Missouri regulators, the Grain Belt project won a court battle to allow a rehearing in 2018, only to have another court in Illinois overturn that state's approval weeks later. After buying the project, Invenergy sought to overcome landowner objections in Missouri by asking state regulators to designate it as a public utility with eminent domain power to secure rights of way.

Landowner groups and the Missouri Farm Bureau opposing the plan have lost multiple challenges, while Invenergy has sweetened the value for the state. Missouri electric cooperatives gaining access to the project’s power are expected to save their customers about $12.8 million per year in electricity costs. Invenergy is also offering to provide broadband internet service to rural Missouri communities along the same rights of way that the high-voltage, direct-current transmission line will require.

Grain Belt Express is one of many long-range transmission projects that industry studies say are needed to expand the country’s renewable energy supply in a cost-effective way. Wind farms in the Great Plains and Intermountain West, solar farms in the Southwest and Southeast, and wind and hydropower resources in eastern Canada could provide lower-cost renewable energy for states and utilities committing to 100 percent clean power over the coming decades, and avoid forcing them to build more expensive resources closer to home.

But the costs of building new transmission have risen even as the number of miles of projects completed has fallen over the past decade, as lapsing state and federal policies supporting new build-outs have left project developers to contend with the ponderous, nearly decade-long process typically required to build new transmission corridors on their own.