At first glance, there may not seem to be much difference between monitoring a PV system in Germany, the U.S., or Japan -- but the latest report from SoliChamba Consulting and GTM Research, titled Global PV Monitoring: Technologies, Markets and Leading Players, 2013-2017, reveals that the dominant monitoring providers in each of the major PV markets are local. And surprisingly, the three global leading firms among independent PV monitoring providers realized less than a third of their activity abroad in 2012.

Is this simply due to a tendency of PV system owners to choose local firms, or are there strong differences in monitoring requirements that keep these PV monitoring markets distinct and prevent the globalization of supply?

Fundamentally, the technology for monitoring a PV system does not change based on its location. A gateway or data logger is located on-site and collects data from the inverter(s) and other local devices, and sends the information back to a server where it is processed and displayed via a dedicated monitoring software, allowing the owner or operator to track production and detect issues.

The hardware and software technologies used for these functions are extremely similar, sometimes identical, across the various PV markets. Strong differences exist in monitoring solutions based on the system size -- residential vs. commercial vs. utility scale -- but this phenomenon is not country-dependent.

The real difference between PV monitoring markets like Germany and the U.S. lies in the incentive structures that drive investment in solar plants, and the financial vehicles that establish the relationships between the asset, the investor, the consumer, the utility and government agencies. Historically, in a feed-in-tariff market like Germany, the main purpose of a monitoring system has been to ensure high levels of production via effective issue detection. Tracking energy production and calculating feed-in tariff income is the responsibility of the utility; the PV asset owner does not participate in the process -- except by receiving a statement and a check. Consequently, monitoring systems in most feed-in tariff markets have been focused on managing inverters (and combiners/strings on larger plants).

In the U.S., however, many incentive programs require the asset owner to report energy production to the agency that issues incentive payments -- whether it be monetary, as in California, or in the form of Renewable Energy Credits (RECs), as in New Jersey. In this context, the PV monitoring solution becomes the reference source of data for incentive payments, so it must provide revenue-grade metering functions. This requirement means more than simply collecting data from a meter; it also impacts the way such data is collected, stored, validated and presented. In fact, the differences between metering and monitoring are so fundamental that in the electric utility world, these two functions rely on distinct infrastructures and technologies.

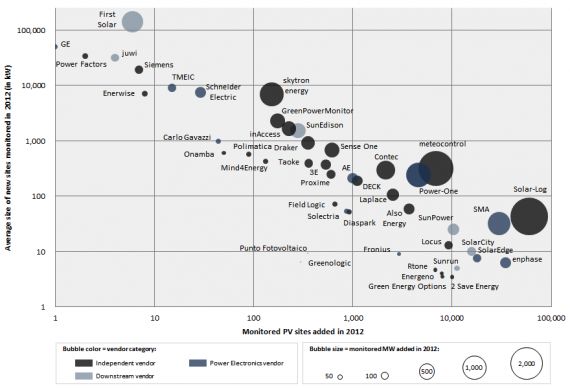

FIGURE: Global PV Monitoring Market by Company, 2012

Source: Global PV Monitoring: Technologies, Markets and Leading Players, 2013-2017

The recent evolution of the German Renewable Energy Act (EEG) is, however, blurring the lines between monitoring requirements in the U.S. and Germany. Under the new law, many residential and commercial systems cannot export more than 70 percent of the PV system’s capacity, and the feed-in tariff for energy exports is lower than the retail price of electricity. This means that self-consumption of solar energy brings better financial returns than exports, and that the power output of the solar system can be regulated depending on the energy usage of the building it is connected to. So several monitoring systems now offer such optimization functions for the German market, which expand the scope of monitoring to revenue-grade meters and bring advanced control functions that are beyond current U.S. market needs.

Another major factor that separates monitoring markets in the U.S. and Germany is the predominance of third-party ownership (TPO) models (solar leasing and power purchase agreements). This business model requires revenue-grade metering so that all parties can rely on accurate measurement of the PV system’s output for invoice calculations and verification of compliance with production guarantees. Incidentally, TPO is also one of the reasons why approximately 80 percent of residential PV systems in the U.S. are monitored, compared with 5 percent to 20 percent in other markets around the world.

In a TPO scenario, although the end-user of the solar energy may be watching the monitoring screen, the TPO provider watches too, as does the investor who owns the asset. Both have a vested interest in making sure that the system is performing as planned. Managing PV systems as assets within investment funds creates a very different set of requirements for monitoring software. This increases the specificity of markets with TPO, mainly in residential and commercial markets, since utility-scale systems are commonly investor-owned in most parts of the world.

So we have seen that there are fundamental differences between the U.S. and Germany, but what about other feed-in tariff markets like Italy and the U.K.? These are theoretically similar to Germany in terms of market dynamics and thus more accessible to foreign firms.

Indeed, SoliChamba Consulting and GTM Research found that four of the top five independent monitoring firms in Italy were foreign firms, both in terms of megawatt count (lead by Spanish firm GreenPowerMonitor) and in site count (lead by Solar-Log from Germany).

The U.K. market, on the other hand, remains largely dominated by British players, many of which are either startups (like Sense One Technology, leading in megawatt count) or home energy monitoring firms expanding to PV monitoring (like Green Energy Options, leading in site count). The U.K. PV market is still young and going through extreme growth, and it is too early to draw conclusions. We may see more aggressive attempts from foreign firms to conquer it in 2013 and beyond.

Asian markets have different dynamics. Japan is one of the oldest PV markets in the world, so naturally it has its own set of monitoring firms. Japanese clients typically prefer local providers, so the odds of a foreign firm becoming a leader in Japan are very low, except via merger or acquisition. China is a new market but the barriers to entry (language, culture, politics, etc.), the extreme pressure on price and the intellectual property risks are strong deterrents for foreign firms. India is also a very young market, although much more open. Local firms are emerging and several foreign firms are competing for this battleground market.

As of 2013, the PV monitoring market is not yet globalized. In most countries, local firms achieve leadership, and the global rankings of monitoring firms are largely a reflection of the relative size of their home markets (hence the presence of three German firms at the top of the global pyramid of independent providers). This may change in the future, but it is likely to be a very slow phenomenon unless accelerated by mergers and acquisitions. In the meantime, we will continue to see local players thrive in local markets.

Regardless of the global or local nature of the PV monitoring market, the driving force behind many firms’ attempts to expand to other countries is the quest for scale. Developing monitoring software and hardware involves a lot of fixed costs, so a provider's profitability hinges on its volume of activity. As long as domestic markets show growth, vendors are less motivated to risk entering new markets. When growth slows or disappears, as happened in Spain a few years ago and is expected in Germany and Italy in 2013 and beyond, many vendors -- small and large -- will probably pursue a global diversification strategy.

For more competitive analysis on PV monitoring technologies and the companies active in the market, learn more about our new report, Global PV Monitoring: Technologies, Markets and Leading Players, 2013-2017, at www.greentechmedia.com/research/report/global-pv-monitoring-2013-2017.