Because of the continued haggling over net energy metering (NEM), PV solar’s most fundamental incentive, GTM Research brought together an advocate and a utility representative to debate the policy at its U.S. Solar Market Insight Conference.

Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) (NYSE:PCG) wants its RPS-required renewables portfolio and rooftop residential to grow, according to PG&E Director David Rubin. But “as the industry moves from a relatively nascent one to one that is mature, it is appropriate to take a careful look at incentives available for customers who install rooftop solar systems.”

PG&E’s decoupled regulatory environment, Rubin explained, leaves earnings unaffected by increased solar. But “a combination of NEM, where a customer can spin their meter backwards at the full volumetric rate, combined with our residential rates, which at this point bear no real resemblance to costs, creates a potential problem for our non-participating customers. I am not here to condemn NEM.”

It is the underlying rate design, he explained. Rates “are steeply tiered. At the margin, our customers are paying $0.30 to $0.34 per kilowatt-hour.”

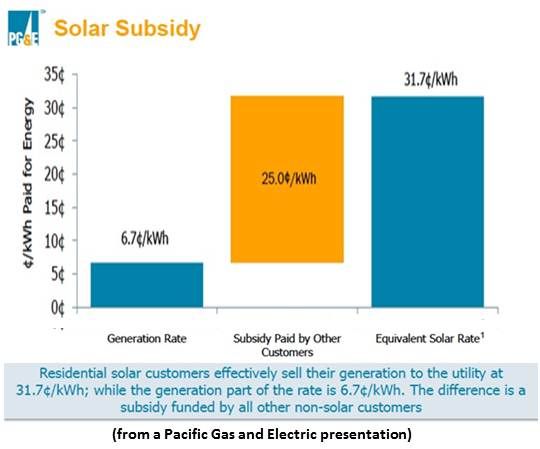

A typical PG&E solar customer, consuming 1,000 kilowatt-hours per month, has an average rate of $0.23 per kilowatt-hour. By PG&E’s calculation, its avoided cost, he said, is about $0.07 per kilowatt-hour.

The California Public Utility Commission (CPUC) market price referent, he added, is around $0.10 per kilowatt-hour. “Somewhere between those two numbers is the correct reflection of how much we avoid when a customer installs solar,” he said. “The difference between that and $0.23 ends up being shouldered by our other customers.”

“You need to look at the costs and benefits of net metering,” responded Keyes, Fox and Weidman Partner Jason Keyes, whose law firm represents the Interstate Renewables Council (IREC), a nonprofit advocate for fair utility pricing.

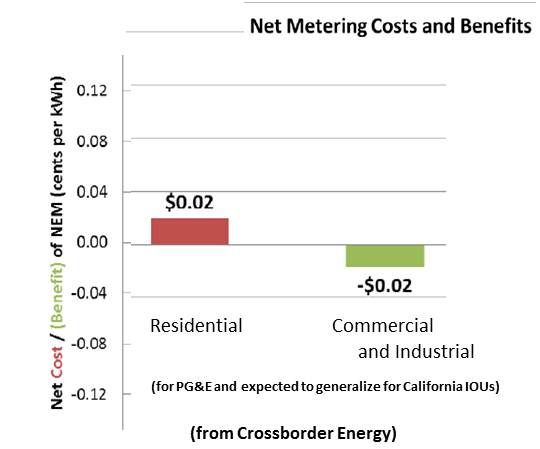

Costs and benefits vary from utility to utility, he said, and from market to market. “In the residential market, the average is $0.23 per kilowatt-hour and often in the $0.30 range,” he explained. “But two-thirds of the market for net metering is the non-residential sector.” Because that market pays demand charges as well as energy charges, he said, its solar use is a benefit to utilities.

“We agree with how the CPUC has handled the costs and benefits of net metering,” he said. “You don’t want to look at net metering generation going to onsite power. You just want to look at the excess.”

And, he said, any subsidy imposed on ratepayers due to the tiered rate structure is “not a cost of net metering -- that’s a cost of that tier system.”

The biggest cost of NEM, Keyes agreed, is the rate. But “the $0.23 is a revenue reduction. The utility isn’t actually paying me $0.23 per kilowatt-hour when I generate electricity. It gives me a kilowatt-hour in the middle of the night.” He rejected the idea of administrative costs because advanced meters should eliminate them, but he accepted there are interconnection costs.

“On the benefit side, the biggest thing is capacity,” he said. Solar adds to a utility’s generating capacity, saving it the costs of purchased peak demand sources.

“I agree our commercial industrial rates are pretty well-designed rates. That is not where we have an issue,” Rubin replied. But “there is strong rationale to design residential and small commercial rates where the revenue and costs match each other much better.”

Rubin said a CPUC study required including both power consumed onsite and exported power. Keyes said that was only because it was legislatively mandated and the CPUC has publicly stated it will focus on exported power.

“I do agree residential will tend more toward a subsidy than commercial,” Keyes acknowledged. But “an E3 study said the rate impact of NEM is fairly modest.” And since tiered rates have flattened since that study, he said, “any subsidy the upcoming E3 study finds should be even more modest. And I would expect it, like the first one, to again find a net benefit on the commercial side.”

Debate moderator and GTM Research Vice President Shayle Kann asked Rubin if a rate structure fix could make NEM acceptable.

“One of the most straightforward things,” Rubin answered, “would be to flatten the rates.” A fixed charge similar to that imposed by the Sacramento Municipal Utility District of perhaps $25 to $30 per month could be an alternative. Or utilities could add demand charges for residential customers.

“There is a commission proceeding on the California IOUs’ residential rates,” Rubin said. If the rate issue is not resolved, NEM customers might be stripped of their exemption “from charges that other types of distributed generation customers pay because they don’t have the same exceptions NEM customers have.”

Social policy underscores the question of “what you would be willing to pay for your neighbor to reduce their bill,” Rubin said. Upward pressure on PG&E rates from the state’s RPS will likely add 10 percent by 2020. “To the extent that NEM adds additional upward pressure, which we believe it does, the question is whether that is an acceptable cross subsidy within our customer base.”

“The current structure of net metering works pretty well,” Keyes said. “For most utilities, there is a benefit.” Eventually, he added, "utility peak demand will shift to later hours and the benefit of net metering won’t be there. But that point is a long way off.”