A coalition of industry, power and oil and gas firms in the U.K. are collaborating on a net-zero industrial cluster that they believe will establish a template for any country seeking a carbon-neutral economy.

Earlier this year, the U.K. became the first major economy to set a target of net zero by 2050. But concrete proposals on how the country could get there are few and far between, with Brexit and (yet) another election dominating the political agenda.In the meantime, the private sector is busy making its own plans, and the most advanced proposal so far was presented earlier this month.

Enter Drax. The company used to be best known for running the Drax Power Station, a 4-gigawatt coal-fired plant in the north of England. Today 2.6 gigawatts have been converted to biomass. The Drax Group has a spinoff in the U.S. producing wood pellets, pumped hydro and a pipeline of gas power-plant developments.

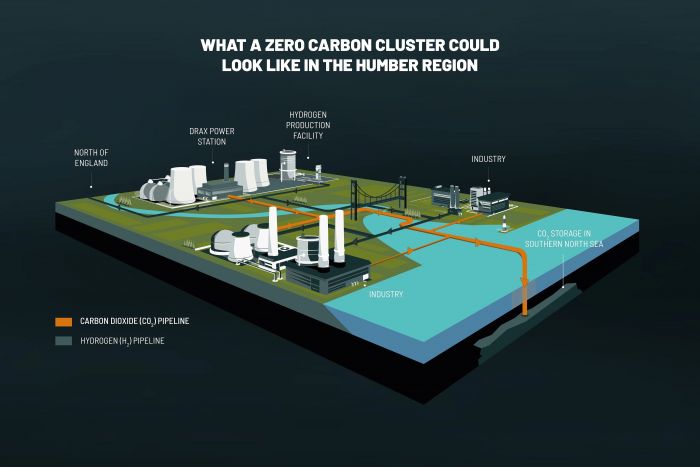

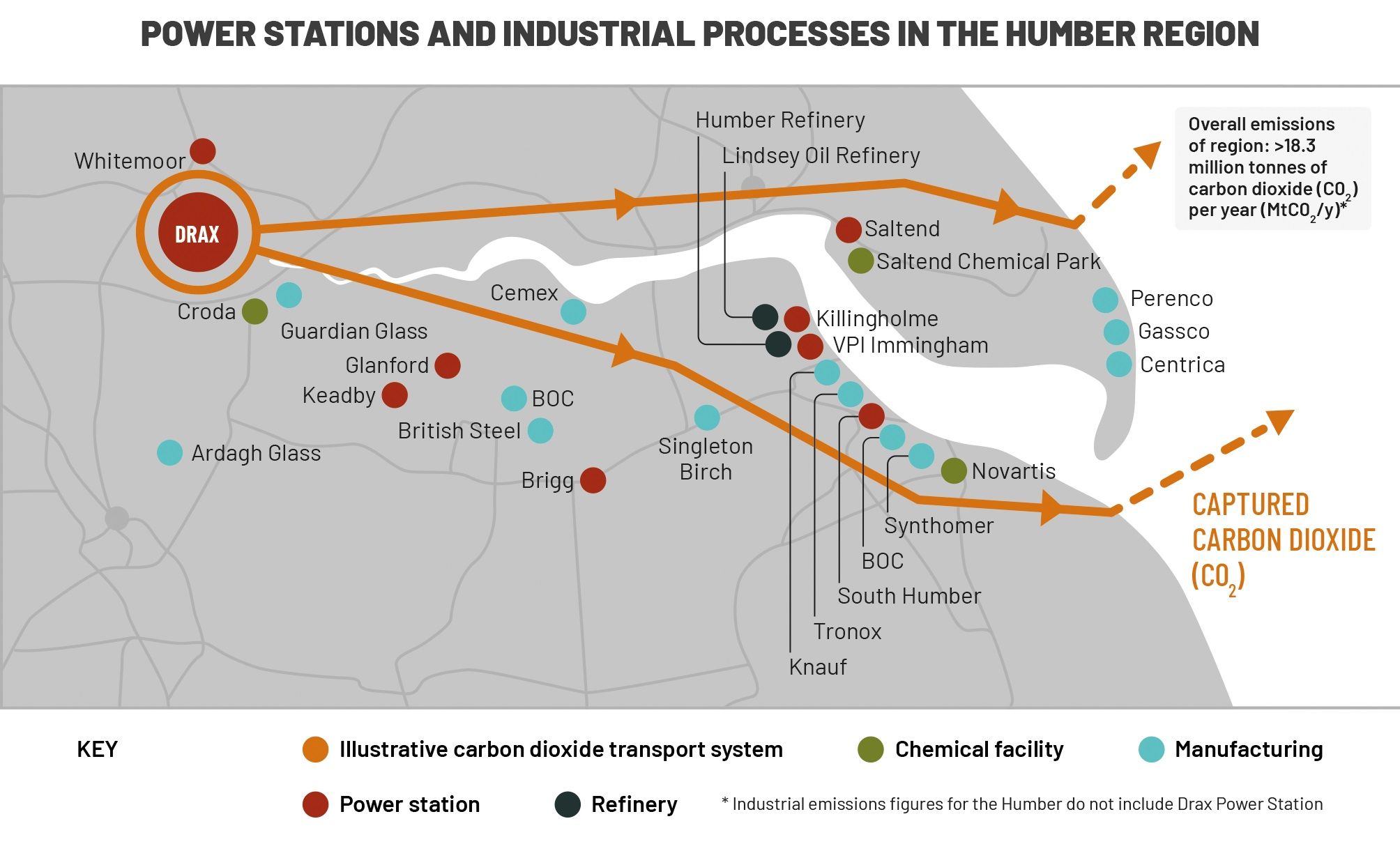

This mixed-fuel power complex on England’s east coast is at the heart of an early proposal to send the U.K. on its way toward a net-zero economy. Its biomass generators will be connected to carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technology.

Meanwhile, National Grid, which runs the U.K. power transmission network and gas distribution grid, will create a regional CO2 network offering industry and petrochemical complexes down the Humber River the chance to feed into the pipe. At that point, Norwegian oil and gas major Equinor gets involved, providing a long-term home for that CO2 in the North Sea.

In tandem, the negative-emissions electricity at Drax will create hydrogen that will be distributed down the Humber industrial cluster via a new network to be developed by National Grid.

The timelines for the project, particularly the CCUS component, could be shorter than expected.

In the first half of this decade, a concerted effort to get the technology up and running in the U.K. ultimately failed. Then the government spent £100 million ($129 million) helping potential projects develop with two making making it to the final stages of predevelopment.

Despite the plug being pulled on both, the companies involved (Drax, Shell, and the utility SSE, to name a few) laid a lot of the groundwork. Drax completed the front-end engineering design for the White Rose project, a new-build coal plant that could have achieved 90 percent capture.

Having worked on many of those projects, National Grid Venture is ready for another crack at it.

"NGV has strong knowledge and expertise in this area, having developed multiple U.K. CCUS projects over the last decade, including Longannet, Don Valley and White Rose,” the company said in a statement emailed to GTM.

“By utilizing our previous knowledge, NGV has also developed the Endurance store — a saline aquifer located 90 kilometers off the east coast of England in the Bunter sandstone formation in the southern North Sea. It is ideally situated to facilitate CCUS developments in the Humber region and could potentially be used by other cluster developments, such as Teesside in the northeast of the U.K. or Rotterdam in the Netherlands.”

CCS: Different this time?

If promising projects with strong support from industry and government could not get off the ground five years ago, what has changed?

Emrah Durusut is an associate director of Element Energy, the consultancy firm hired by the Zero Carbon Humber partnership to analyze the proposals. “Five years ago, we still had good project proposals, like White Rose and Peterhead. But in terms of the narrative about CCS and the value proposition, we were discussing the wrong things," he told GTM.

"We were trying to focus on the wrong aspects of CCS, and people were still discussing renewables versus power with CCS. It’s not a very useful discussion; we need both and we know that now,” Durusut said.

“Today, we're talking about more exciting things, things around industrial decarbonization, for example, and CCUS has a vital role to play in that.”

He points out that some sectors, like cement and steel, rely on processes that don’t have low-carbon alternatives, so offering a capture option is essential.

Other industrial clusters are looking at their options, too, and while not all have the luxury of an existing gigawatt-scale biomass plant on their doorstep, there are other routes to negative emissions. Biogas with CCUS can be applied in the power sector or at smaller industrial scales in place of natural gas.

The influential Committee on Climate Change, the U.K. government’s independent adviser, produced a report on what net zero by 2050 means. It estimates that 5 gigawatts of bioenergy paired with carbon capture will be needed across the U.K. by the target date. It also recommends that in the longer term, industry should only be using biomass if it is pairing it with CCUS.

With the target for emissions reduction raised from 80 to 100 percent by 2050, CCUS is considered an essential industry for the U.K. Hitting this target across all sectors is where the second major component of the Humber plan comes in.

Hydrogen's role

While gas has been championed by many in the power sector, Durusut said natural gas simply is not good enough for net zero. Hydrogen can play a role in transport, heat and industry.

The Zero Carbon Humber plan proposes the construction of a major hydrogen production facility next door to the Drax power station. Drax recently got the nod to develop 3.6 gigawatts of natural gas and energy storage at the same location as the biomass station. It could produce hydrogen from natural gas, with the CO2 sent for storage and the hydrogen distributed via NGV’s dedicated grid.

The hydrogen would then be used for some of the trickiest sectors to decarbonize: heat, heavy transport and industry.

Equinor predicts it could heat 3.7 million homes using hydrogen derived from its natural gas via a 12-gigawatt production facility. By its calculations, if the CCUS were in place on time, that would be 3.7 million homes getting zero-carbon heating by 2034.

Picking up the tab

So who pays for all this — and how?

Decarbonization in the U.K. power sector has thus far been achieved through intervention, most notably through the contracts for difference system, with the costs recovered through energy bills. But for industries like steel, prices are set internationally. If costs go up, such industries will find somewhere else to operate and take their jobs with them.

Retaining jobs in heavy industries that would otherwise shift overseas is a big incentive for the economy. To keep such jobs, Durusut argued, those industries will need the tools to decarbonize — namely, hydrogen and CCUS.

“Five different areas will require specific business models with specific potential incentives to make it work,” he said. The most pressing is getting CCUS storage in place for the power sector. The best option for doing that, Durusut said, could be an existing mechanism: the contracts for difference incentive.

"[CFD] already exists, and it was a reason why renewables production has been proven successful,” he said.

Durusut suggests that the CFD incentive should initially be offered to natural-gas power plants providing baseload with CCUS, with a plan to recover their costs as the load factor of these plants falls, more renewables come online and gas comes to be used principally for flexibility.

A meaningful carbon tax would also have an essential role in the emerging business cases underpinning this reimagination of heavy industry.

While many long-term targets dissolve as government administrations come and go, the political tide would suggest the U.K.’s net-zero target is here to stay. The country’s next government will be the first asked to lay the foundations for Zero Carbon Humber and other initiatives that follow.