It’s neither easy nor cheap to get a piece of action in the U.S. offshore wind market these days, but EnBW has come tantalizingly close.

In last December’s auction for a trio of lease areas, the winning development groups ponied up a record $135 million each for prime zones facing Massachusetts. Bidding through its East Wind LLC unit, EnBW was the last developer left on the sideline — its final offer of $128 million falling just short after more than 30 rounds of bidding.

History seldom remembers the also-rans. But EnBW, a large German utility, still has every intention of putting its stamp on the U.S. offshore wind market. The company’s scale and track record suggest that, even in a crowded field, the market should take those ambitions seriously.

“We were there to the bitter end,” Bill White, managing director of EnBW North America, said of the December auction. “We know that [eventual winner] Vineyard Wind made an exit bid that round, so it was between us and them.”

“As painful as it was to lose, it gave us confidence because we’d valued the market pretty closely,” White said in an interview in the company’s new office in New Jersey.

Focus shifts to the mid-Atlantic

The Massachusetts auction underscored just how rich the stakes have become in the U.S. offshore wind market. The winning groups were all backed by deep-pocketed global energy companies, including Shell New Energies and Norway’s Equinor.

In the face of such competition, small developers will now struggle to find a way into the U.S. market. But EnBW is among Europe’s largest energy suppliers — with annual revenues of more than €20 billion ($22.4 billion), and a decade-long track record of building and operating offshore wind farms off Germany’s northern coasts. It has more than 600 megawatts under construction in the North Sea right now.

Like all major German utilities, EnBW has been forced to transform the way it thinks and invests in response to the country’s Energiewende, or pivot from nuclear energy and toward renewables. And like many European utilities — EDF, Ørsted and Enel among them — EnBW is now looking to the vast U.S. renewables market for growth.

Its first big step into the U.S. came a year ago, when the company formed a joint venture to develop a floating project off California with Trident Winds, a small developer based on the West Coast. These days, EnBW has “refocused” its efforts around the nearer-term opportunity in New York and New Jersey, White said.

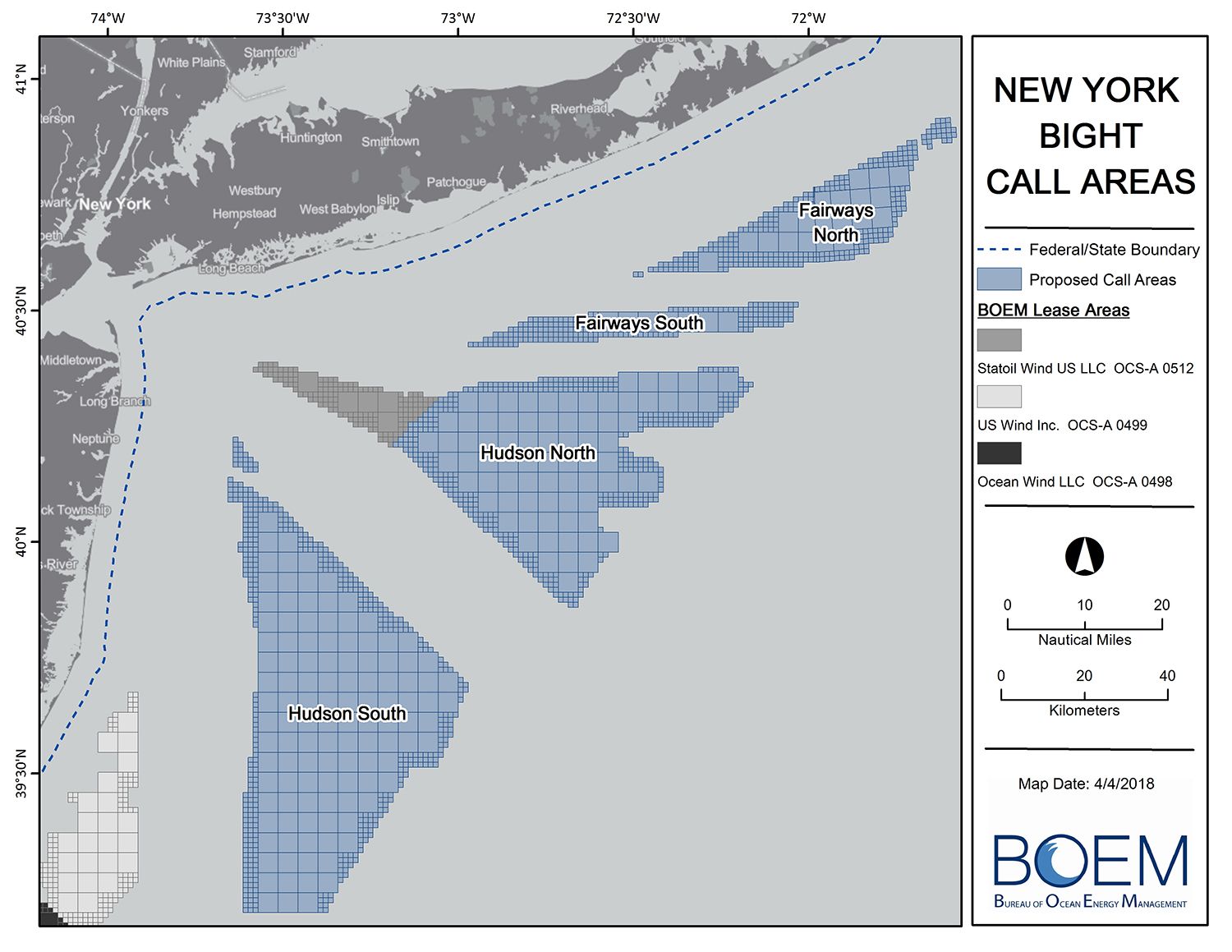

The next obvious chance for developers to gain control of a lease area in federal U.S. waters is an auction likely to come in 2020, for zones near New York and New Jersey, in the area referred to as the "New York Bight."

The opportunity for selling renewable power from those zones is enormous, with New York having significantly increased its offshore wind target to 9 gigawatts by 2035 and New Jersey required to procure 3.5 gigawatts by 2030.

Put together, New York and New Jersey may be the “largest regional offshore wind market in the world right now,” White told Greentech Media.

New York Bight zones (in blue) potentially up for grabs in a lease auction next year.

“We’d like to secure a lease area as soon as the auction takes place, hopefully early in 2020, and then think about what it will take to win [an offtake deal] either in New York or New Jersey,” White said. “That’s the primary focus of our company right now.”

EnBW is also putting development efforts into a region to the north of Massachusetts, in the deeper waters of the Gulf of Maine, that could emerge as a market over a longer timeframe.

White said the company has met with the administration of New Hampshire Governor Chris Sununu, which is “very interested” in offshore wind, and is engaged with Maine. Projects built in these waters could serve not only those states but also potentially southern New England via Massachusetts.

According to Søren Lassen, senior offshore wind analyst at Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables, EnBW is the second-largest offshore wind player in Germany and the sixth-largest in Europe, in terms of its operational and secured portfolio.

"In terms of globalization, EnBW has so far been less aggressive compared to its European counterparts — both in terms of number of markets and timing," Lassen said. "Nevertheless, EnBW has managed to secure pipelines both in Taiwan and the U.S. West Coast. This underscores EnBW’s willingness and capabilities to make it outside its domestic market."

Second-mover advantage

New England may have gotten a head start in offshore wind thanks to Massachusetts’ early efforts, but the mid-Atlantic market is making up for lost time.

Ørsted won New Jersey’s first offshore wind solicitation in June with a 1.1-gigawatt project, while New York last month awarded Ørsted and Equinor another 1.7 gigawatts of future capacity.

Critical to those first projects are the investments the developers are expected to make in the currently nonexistent local supply chain.

Few people better understand the supply-chain landscape than White — a rare U.S. offshore wind veteran, who spent a decade shaping Massachusetts’ market as a state official, including overseeing construction of New Bedford’s Marine Commerce Terminal. He was hired by EnBW last year.

Ørsted is planning to help Germany’s EEW establish a manufacturing facility for foundations in Paulsboro, New Jersey, while New York is planning to marshal $300 million of public and private funding to upgrade and expand its port infrastructure.

EnBW has a longstanding relationship with EEW, among the main suppliers of turbine foundations in Europe's offshore wind market. “Having them come stateside would be a big moment for this industry," White said.

“We’re going to be a 'second mover' in this market and might benefit from some of those investments. But we’ll also be prepared to make those [kinds of] commitments as a company,” he said, adding that EnBW is already talking with several ports.

California floating on the horizon

Meanwhile, EnBW continues to advance plans for a project off California through its Castle Wind joint venture. In addition to the New York Bight, a second federal offshore wind lease auction is expected in 2020 for areas off California.

Due to the extreme water depths off the West Coast, projects there will need to be built using still-expensive floating technology. Yet despite the challenges, offshore developers are drawn to California for obvious reasons: the state’s huge electricity market and sky-high renewables ambitions. “It’s the demand," White said.

And while floating technology is expensive today, it could ultimately prove cheaper than turbines that must be affixed to the seabed, he said.

Floating installations are likely to require less steel, White pointed out. The Jones Act, seen by many as an impediment to the U.S. offshore market, is less of an issue because floating turbines could be towed to sea by existing vessels. And there’s less of an impact on marine mammals due to the lack of pile driving.

“A lot of thinkers in the offshore wind industry — including our partner [and Trident Winds CEO] Alla Weinstein — believe that floating is really the breakthrough next-generation opportunity for this industry, allowing us to build in waters that are deeper and farther offshore,” White said.

It's only been four years since Massachusetts' Cape Wind project collapsed in spectacular fashion. At that time, people told White, "Bill, God bless all the efforts you guys [in Massachusetts] put in, but this industry has been set back 10 years."

Four years later, "the U.S. market, and particularly the Northeast, is moving forward with more speed and certainty than anyone could have imagined," he said. "People are still in awe of what's going on."