A few long and hectic days co-opted otherwise muted expectations from the 13-day U.N. climate change negotiations held in Durban, South Africa. The final days featured heated protests leading to the ejection of several NGO leaders, talks bleeding into the wee hours of Sunday morning, high-level ministers from small developing states leaving the table to catch flights back home, and a late showdown pitting the EU and India negotiators against one another. But for the 17th year, the international community can once again reaffirm the faith and necessity of an international forum on climate change.

The results, including the so-called “Durban Platform,” outline an “agreed outcome with legal force under the convention applicable to all parties” to be determined by 2015 and to come into effect by 2020, essentially creating a new roadmap towards an internationally legally binding climate treaty by 2020. Furthermore, two major expectations going into the conference were achieved: the formal establishment of the nebulous Green Climate Fund (GCF) that originated last year in Cancun, and an extension to the Kyoto Protocol through 2017. However, although the proposed annual $100 billion GCF now has staff and an office, the instruments by which developed countries will finance the climate fund remain undetermined. In addition, the Kyoto Protocol continues to fray as developed economies like Japan, Canada and Russia formally pulled out of binding targets. Still, the Durban conference is being hailed in many outlets as a small victory and another baby step towards international action on climate change, despite the fact that the promise of a legal outcome does not necessitate an actual legal outcome in 2015.

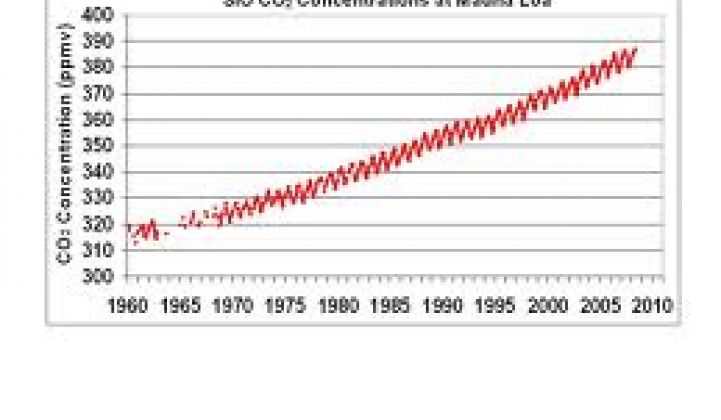

Environmental groups continue to point out that individual players, including the U.S., have been slow-moving, lacking in international ambition and cooperation, and missing the key emphasis on “common but differentiated responsibility” -- a phrase codified by the Kyoto Protocol that essentially keeps the burden of tackling climate change on those historically responsible for climate change. Last month, the International Energy Agency reported that greenhouse gas emissions must peak in the next five years in order to meet the average global warming temperature target of 2 degrees C set by the Copenhagen Accord and the Cancun Agreement. UNEP’s own report on the so-called Emissions Gap showed that current pledges from Copenhagen and Cancun would lead to a 5-gigaton greenhouse gas emissions gap with a path consistent with 2-degree warming; the result of the voluntary pledges, many of which are conditional, would be global warming on the order of 3.5 to 4 degrees C and a host of climate change-related disasters.

Representatives from the Climate Action Network (CAN) point out that “the U.N. climate talks are only as strong as the political will that drives them -- or drag them. While countries have kept the political space alive, without a serious ramping up of ambition and action from developed countries, the deal to prevent the climate from moving past crises to catastrophe will remain elusive.”

Widespread public backlash against the delayed progress first bubbled up on Sunday, December 4, as thousands of activists marched through the streets of Durban demanding a range of policy changes, from an ambitious and binding treaty to a broader call for climate justice. Throughout the second week of negotiations, civil society, especially youth NGOs, grew bolder. [Full disclosure: I was attending the climate talks to assist youth-based NGOs.] On Tuesday of the second week, six young Canadians were thrown out of the talks for turning their backs on Canadian Environment Minister Peter Kent during a plenary session. Two days later, Abigail Borah, a New Jersey resident, was ejected after interrupting U.S. lead negotiator Todd Stern with the call of unshackling the U.S. international position on climate change from congressional obstructionists. On Friday, a large group of activists, including official party delegates from Egypt, the Maldives and other climate-vulnerable countries, marched toward the closing session demanding binding and more ambitious climate targets, which led to the removal of leaders from Greenpeace, 350.org, Friends of the Earth, and many others.

The outrage from civil society seemed to have pushed the needle just enough. Immediately following Borah’s interruption, the U.S. state department pushed forward its 2:30 p.m. press conference shifted to 12:30 p.m. and appeared to backtrack on its adherence to a 2020 timeline for a climate deal. With the U.S. seemingly marginalized by the perception of blocking progress, negotiators from the EU, India and other developing states took leadership and center stage. The Chinese climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua delivered an impassioned speech after midnight Sunday that had many scrambling for better translators: “What qualifies you to tell us what to do? We are taking action. We want to see your action.” Similarly, tired of accusations of stalling the talks, India’s Environment Minister Jayanthi Natarajan laid into the nebulous EU plan of a roadmap toward universal binding targets: “Am I to write a blank check and sign away the livelihoods and sustainability of 1.2 billion Indians, without even knowing what the EU ‘roadmap’ contains?”

In the final moments, international negotiators crowded around a face-to-face meeting between the EU and Indian lead negotiators on the issue of legality: would Durban call for a legally binding framework to be established in 2015? In the end, both negotiators agreed to the phrase “an agreed outcome with legal force” as a compromise between “legally binding” and “legal outcome” -- and perhaps the tensest minutes of the negotiations passed.

While the past two weeks may showcase continued commitment towards an international framework to address climate change, the drama underpinning the talks seemed disturbingly unmatched to the growing urgency of the need for an ambitious climate treaty.

“While governments avoided disaster in Durban, they by no means responded adequately to the mounting threat of climate change. Powerful speeches and carefully worded decisions can’t amend the laws of physics. The atmosphere responds to one thing: emissions. The world’s collective level of ambition on emissions reductions must be substantially increased, and soon,” according to director of strategy and policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, Alden Meyer.

As climate negotiators begin preparations for next year’s negotiations in Qatar, a host of new questions for the international and climate-affected communities will come to the forefront. Is there a way within the established outcome to bridge the emissions gap between the desired target of 2 degrees C and current pledges? How will the Green Climate Fund be financed? Will important steps on measuring, reporting and verifying emissions reductions be codified? Will the U.S. continue to sidestep leadership at the international negotiations on climate change?

With the final question in mind, I close with a video produced by U.S. youth at the climate change negotiations in Durban, including youth representatives from Project Survival Media, the Sierra Student Coalition, SustainUS and many others: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mQVpZQ1UlKw.