NASA plans to launch a satellite early next year to track carbon dioxide emissions. The launch is part of a data-gathering mission that could affect climate change policies and carbon emissions trading worldwide.

The satellite, Orbiting Carbon Observatory, is scheduled for launch from the Vandenberg Air Force base in California some time after January 2009.

"The idea is to fly over the Earth and look down and measure columns of CO2" said David Crisp, who heads the research at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Researchers hope the OCO will provide data to help answer some questions about how nature wipes clean a large amount of carbon dioxide emitted by human activities. The question they are seeking to answer is: What is the carbon dioxide concentration in different parts of the world and what causes it?

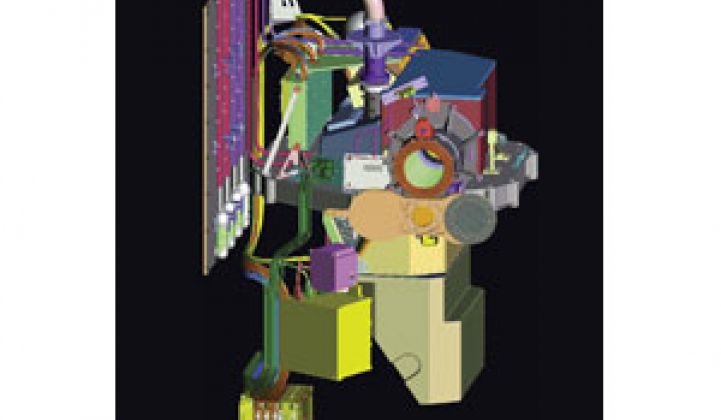

The OCO is the first NASA spacecraft dedicated to studying carbon dioxide. It will orbit the Earth at an altitude of 705 kilometers (438 miles) and take carbon dioxide measurements three times a second using three spectrometers.

The compact satellite – at 2-meters tall and 1.9-meter wide – will cover the whole Earth every 16 days, said Crisp. He and a fellow researcher, Scott Denning, presented their $270 million research project at the American Geophysical Union's meeting in San Francisco Tuesday.

Scientists have been collecting carbon dioxide data on the ground for decades, but those projects aren't able to easily cover a wide swath of area. Better scientific instruments and supercomputers also enable researchers to improve data collection and analyses of this important greenhouse gas.

NASA isn't alone in its attempt to measure carbon dioxide high in the air. Other countries, such as Japan and the European Union, also have their own carbon satellite projects.

Data collected by the OCO will help researchers figure out the geographic distribution and seasonal variations of both naturally occurring and man-made carbon dioxide. The results will allow scientists make more accurate predictions of the impact of climate change.

The data also could influence policy makers when they set emission-reduction goals and limit emissions by industrial polluters. The United Nations is currently drafting a climate change treaty to succeed the Kyoto Protocol, in which 37 industrial nations agreed to take steps to cut emissions by 2012 (see U.N. Climate Talks Poses Big Impact on Greentech).

Trading carbon emissions, of course, is a big business, growing from $67 billion to $84 billion during the first nine months of this year, according to New Energy Finance, a market research firm in London.

Researchers hope to use data from the OCO to confirm some of the theories about how, where and in what amount carbon dioxide is being produced and where it goes. The gas can occur naturally or be produced by human activities, and nature acts as a sponge to soak up carbon dioxide and remove it from the atmosphere.

When scientists used available data to model what carbon dioxide concentration was like before Industrial Revolution in 1751, they determined that the carbon dioxide levels rose less than 1 percent over a 10,000-year period. The levels went up 37 percent between 1751 and 2003.

About 60 percent of those man-made emissions have disappeared from the atmosphere, however. Cold ocean water, it turns out, is a great absorber of carbon dioxide, said Denning, who also is a professor at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, Colo. So is land – but researchers don't know exactly where and how.

Researchers have many theories though. One belief is that the increase in man-made carbon dioxide has fueled plant growth. The discovery that plants are growing at a faster rate than they are dying means there are more plants to swallow up carbon dioxide, a key ingredient for their growth, Denning said.

Another theory surmises that reforestation efforts on some parts of the planet and wildfire suppression initiatives also help to preserve vegetation and reduce carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The OCO mission could help researchers determine how nature controls carbon dioxide emissions by detecting the levels of concentration in different parts of the world. The two-year project will generate terabytes of data. Scientists plan to make the data available to the research community nine months after the launch.