Earlier this month, my coauthors and I recommended transforming state renewable portfolio standards (RPSs) into more ambitious low-carbon portfolio standards (LCPSs). Such a policy change would save many of America’s imperiled nuclear power plants from premature closure, while also encouraging the long-term deployment of advanced nuclear, renewable and carbon-capture technologies.

Our report, published by the Breakthrough Institute and Environmental Progress, was released at a Department of Energy event on improving the economics of nuclear. (You can watch the video here).

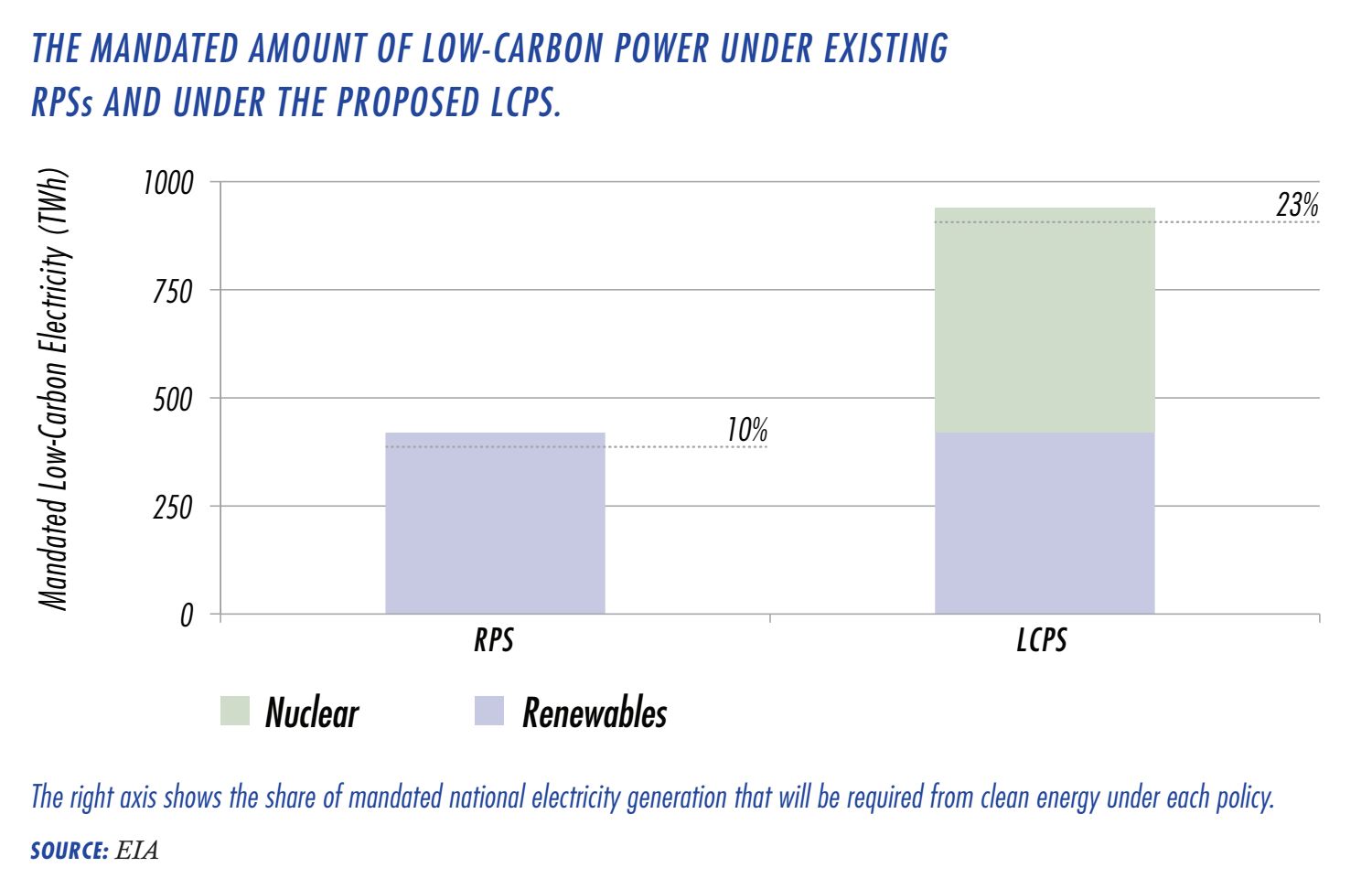

Looking at the big picture, moving to LCPSs could provide real, significant benefits to the United States. Just adding existing nuclear capacity to RPSs in the states that have both an RPS and existing nuclear would more than double the statutory requirements for clean energy in this country, from 420 terawatt-hours annually by 2030 to 940 terawatt-hours.

Assuring this additional power comes from low-carbon sources would prevent 320 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions -- 17 percent lower than would otherwise be the case.

How realistic is this recommendation? I’d say it’s very feasible.

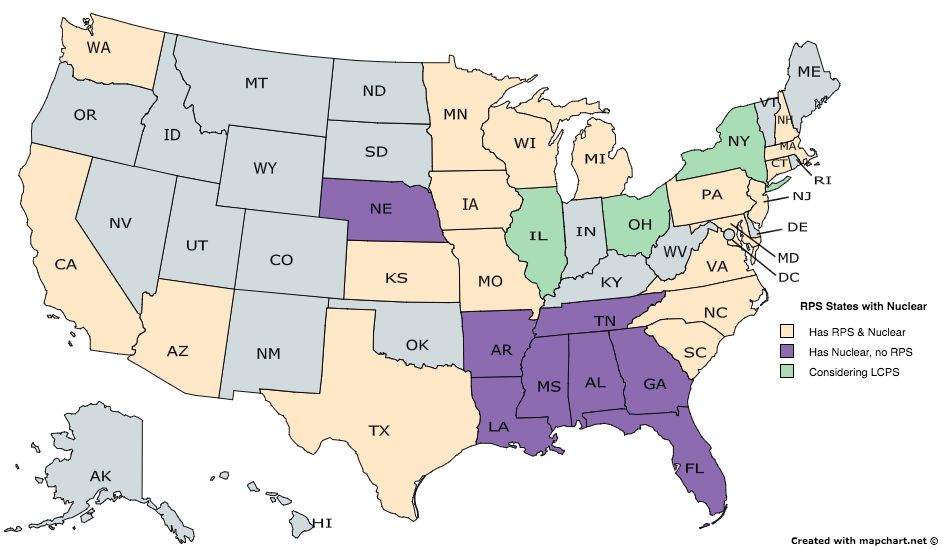

States with RPSs already have more nuclear power than states without -- not to mention the policy infrastructure of having RPSs in the first place. A straightforward transformation is eminently possible, and would certainly be worth it, considering all the carbon emissions we could avoid emitting.

Below I’ve shown the states around the country that have RPSs and nuclear capacity, as well as states with nuclear power plants but no RPS. I’ve also highlighted the states that are already working on creating some version of an LCPS -- states that could be an example for dozens more down the road.

But why LCPS, and why now? Isn’t America already making progress toward a clean energy future?

Yes and no.

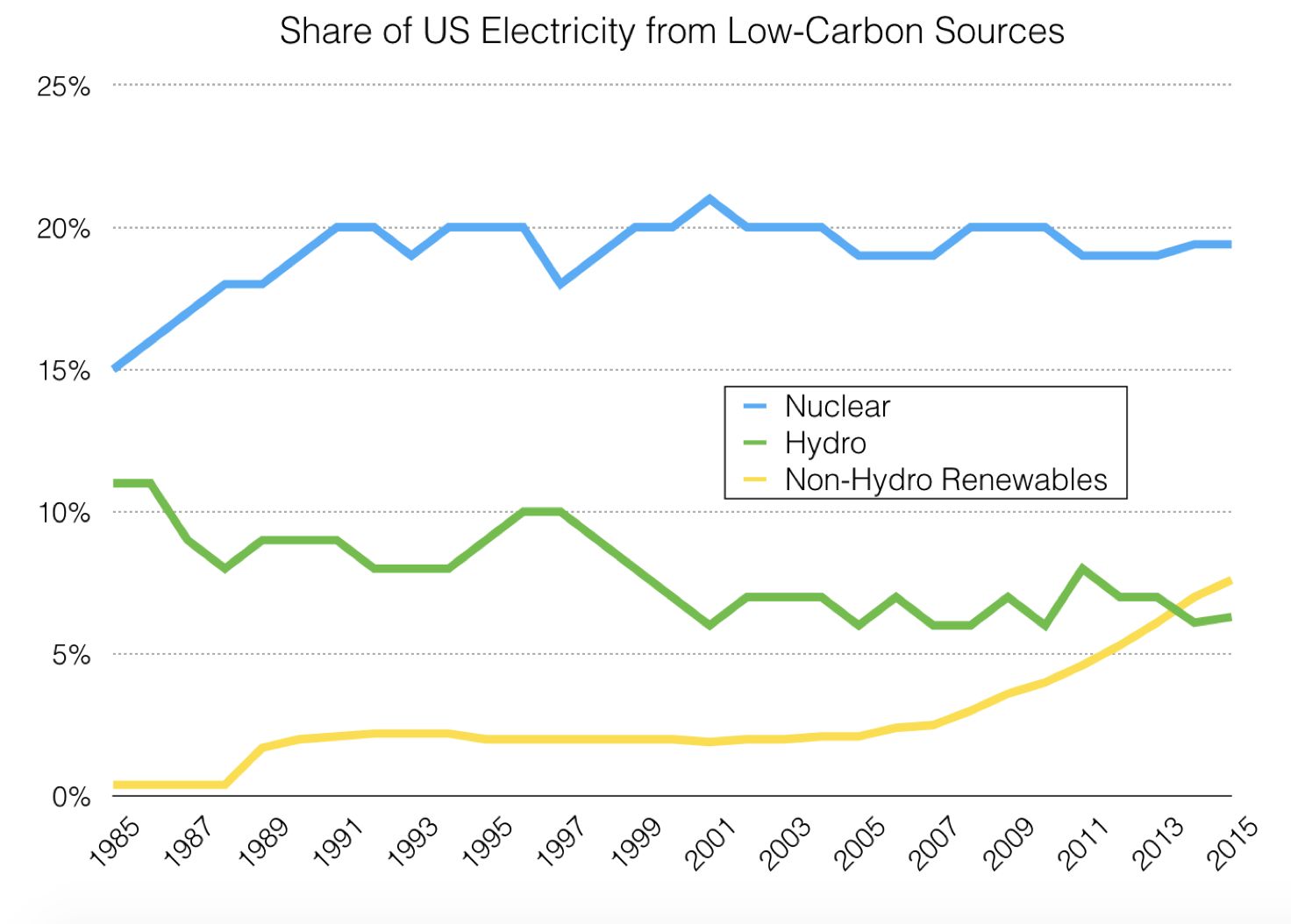

Renewable energy -- mainly wind and solar -- have been growing impressively, especially in the last five years. But the nation’s share of clean energy has actually not improved much at all in the last generation.

Today, low-carbon power technologies generate 33 percent of U.S. power, compared to 29 percent in 1989.

Even if wind and solar continue their recent growth rates, low-carbon electricity deployment is not growing fast enough to reach ambitious decarbonization goals. Those goals face even stiffer headwinds with every nuclear plant that closes. Even if nuclear power is replaced by wind and solar -- something that hasn’t happened once anywhere in the world -- it amounts to low-carbon replacing low-carbon.

Compounding this problem, there has been a national decline in hydroelectric generation, down 27 percent from its peak in 1997.

Several states are already considering more inclusive low-carbon standards that include nuclear. Ohio’s low-carbon portfolio standard allows 12.5 percent of the 25 percent target to be sourced from technologies other than renewables, including nuclear power. Unfortunately, the phase-in of Ohio’s standard has been frozen and may be reversed by the state legislature. Illinois also has a bill pending in the state legislature that would change the state’s RPS of 25 percent to an LCPS of 70 percent. New York is looking to implement a Clean Energy Standard that would support nuclear in addition to a more ambitious RPS.

LCPSs represent a promising policy tool to protect America’s clean, economic nuclear fleet. In the long run, they’ll be just part of a decarbonization scenario that includes protecting today’s clean power, deploying existing low-carbon technologies, and innovating toward cheaper, more scalable clean energy technologies.

***

Jessica Lovering is director of energy at the Breakthrough Institute. She is the coauthor of a new report, Low-Carbon Electricity Standards. Follow her at @J_Lovering.