California Governor Gavin Newsom last week released a long-awaited report on California’s policy options to reduce the risk of utility-caused wildfires, as well as wildfire-caused utility bankruptcies like Pacific Gas & Electric’s.

The report laid out a slew of recommendations, from massive changes in forest management and land use to major utility regulatory and safety reform, for state lawmakers and regulators to consider in the crucial months before the start of the 2019 fire season.

But it stopped short of endorsing a step that Wall Street, credit ratings agencies, and California utilities themselves have been seeking — and which may be the surest path to preventing future utility bankruptcies.

That’s changing the state’s "inverse condemnation" legal doctrine, which holds utilities liable for damages from fires caused by their equipment, whether or not they’re negligent or at fault.

This doctrine not only drove PG&E into bankruptcy protection in January, but has also pushed down the credit ratings of California's other investor-owned utilities, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric. And because utilities face the immediate pressures of these multibillion-dollar liabilities for months, if not years, before they can hope to seek recovery through regulator-approved rate increases, "financial experts have opined that these utilities are likely one major fire away from bankruptcy," the report notes.

But changing this unique legal doctrine to a more common “fault-based standard,” which would only hold utilities liable when they’re found negligent or at fault for the fire, would require a two-thirds vote of both houses of the state legislature and a majority vote from the state’s voters. Doing so would relax a framework that’s seen by many as holding utilities like PG&E responsible for years of lax safety management.

Doing away with inverse condemnation is also unpopular with insurance companies and the attorneys of victims of the devastating wildfires of 2017 and 2018, which doomed efforts to include it in last year’s legislative wildfire package SB 901.

That may be why, despite citing the need for dramatic reform on how to allocate “responsibility for wildfire costs” to avoid crippling the state’s utilities, Gov. Newsom stopped short of endorsing inverse condemnation reform in a Friday speech introducing the report.

Instead, the report lists changing to a “fault-based standard” as one option between two others seen as more politically likely in the months ahead — creating some kind of fund to cover utility wildfire costs.

The multibillion-dollar question

The report cites two fund concepts, each with accompanying changes in state utility regulatory structure. The first, a catastrophic wildfire fund, has already been proposed in legislation introduced last year, and is currently being worked on for this year’s legislative session.

The second, dubbed a “liquidity-only fund,” shares many of the catastrophic wildfire fund’s core characteristics.

In simple terms, both funds would raise money from utility shareholders and ratepayers (i.e., from the corporation’s bottom line and from increasing customer rates), as well as from stakeholders across the process including insurers, homeowners, state agencies and taxpayers. The money would be made available to utilities when they’re hit with massive wildfire liability claims.

This could help solve a key problem for Wall Street, and one that SB 901’s various measures failed to solve — paying today for wildfire liabilities that utilities might require years to get approved by the California Public Utilities Commission. The CPUC cost recovery process can take 18 months to two years — but in the case of San Diego Gas & Electric’s massive wildfires of 2007, which led the utility to implement what are considered some of the country’s most effective utility fire-prevention capabilities, the CPUC process took more than seven years, the report notes.

While SB 901 does give the CPUC tools to shelter utilities from wildfire liabilities that would cripple their ability to safely, reliably and affordably serve their customers, those tools would likely take as long to give utilities a shot at recovering those costs.

One of the reasons that SB 901 failed to ease the credit downgrades from Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch that helped push PG&E into bankruptcy is because it “did not address the significant time period between the occurrence of a catastrophic wildfire, the payment of damages arising from that wildfire, and the CPUC’s final determination of whether those payments can be recovered in rates,” the report states.

Many challenges remain in creating a working model for these funds, most notably raising enough capital to cover the uncertain future costs of wildfires. And because utilities still have to face consequences for failure to maintain safety, the CPUC will have to examine each fire covered by the fund, and assign penalties including forcing the utility to pay back what they took from the fund if they’re found at fault.

There’s also the key challenge of getting buy-in from insurance companies, which would be asked to accept a cap on their “subrogation claims,” or claims made under the assumption of utility guilt implied under the inverse condemnation doctrine. “If the wildfire fund is not sufficiently capitalized and/or the other stakeholders are not willing to compromise their claims, then the wildfire fund will be exhausted more quickly and ratepayers will be responsible for costs thereafter,” the report noted.

No easy answers

Major questions remain over how California’s current policies and legal doctrines will affect PG&E as it simultaneously moves through bankruptcy reorganization and struggles to improve safety to prevent another catastrophic wildfire this season.

Earlier this year, PG&E was cleared of starting the 2017 Tubbs Fire, which carried an estimated $15 billion in damages, after state investigators found the fire was started by a privately owned electrical system, thus clearing the utility of fault even under the inverse condemnation standard.

But PG&E has conceded that one of its transmission lines was almost certainly the cause of the November 2018 Camp Fire, which replaced the Tubbs Fire as the state’s deadliest and most destructive, making it likely it will face liability for its costs, even if state investigators find the utility did nothing wrong. PG&E took a $10.5 billion charge in the fourth quarter for claims connected to the Camp Fire, and insurers have estimated the total losses could exceed $16 billion.

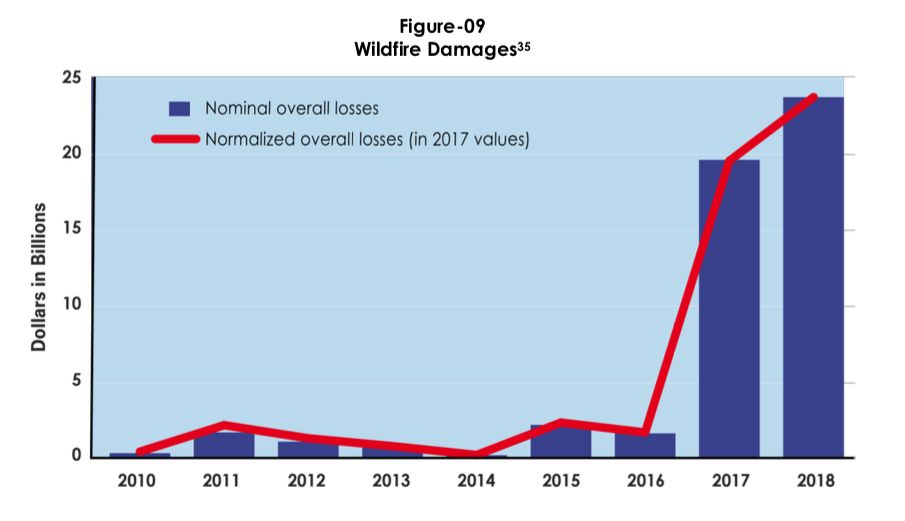

This chart from the report highlights the dramatic rise in the destructiveness of the last two wildfire seasons in California. One key unknown is whether this trend represents a permanent shift for years to come, or if the state’s fire prevention efforts can bring it back down.

But “as long as electrical lines run through tinder-dry forests, California can mitigate but not eliminate utility-sparked fires,” the report notes. If the state does nothing to change its inverse condemnation doctrine, it’s highly likely that utilities will continue to bear the vast majority of these wildfire costs, putting them and the state that relies on them in an untenable situation.

Newsom’s strike force report punted any final decision on how to address these cost-allocation conundrums to the five-member Commission on Catastrophic Wildfire Cost and Recovery established by SB 901, which is set to release its findings in June, as well as to the state legislature, where bills to address a handful of the report’s issues have emerged.

But it’s unclear if Friday’s report release has shifted the view of credit ratings agencies. After all, under the current inverse condemnation standard, investor-owned utilities face limitless liability for wildfires, even if the conditions that are leading to their increase — including the climate change they’re being asked to combat by investing in clean energy — are out of their control.

Toby Shea, vice president at Moody’s Investors Service, wrote in a Friday note that the report “represents concrete progress toward options for managing wildfire risk — a credit positive,” with a combination of strategies that “start to exhibit more promise.”

But he also noted that “none of the proposed concepts will alone mitigate the risk for California’s utilities,” adding that the “credit impact won’t become clear until legislative details addressing liquidity and cost recovery are finalized.”