Utilities planning smart electric grid upgrades can learn from Xcel Energy’s SmartGridCity pilot in Boulder, Colo. -- about how not to effectively communicate with your customers.

Last month, a Boulder judge denied Xcel’s request to regain more than $16 million from Boulder citizens for costs of the upgraded grid. One reason Xcel will have to find those dollars on its own might be because citizen knowledge about the project points to a utility-customer disconnect. Engaging the consumer is a challenging task. If many residents don’t know or care that they are using a smart grid, this lack of information could slow down smart grid progress.

When asked if he had a smart meter on his home, Boulder resident Adam Jackaway was unsure.

“Yes,” he said. “Wait. I don’t know.”

Jackaway holds two master’s degrees in environmental engineering and architecture, and he didn’t know if the contraption on the back of his house was a smart meter. He said that he can log in to his account and see how much electricity he uses each day, but he never actually does.

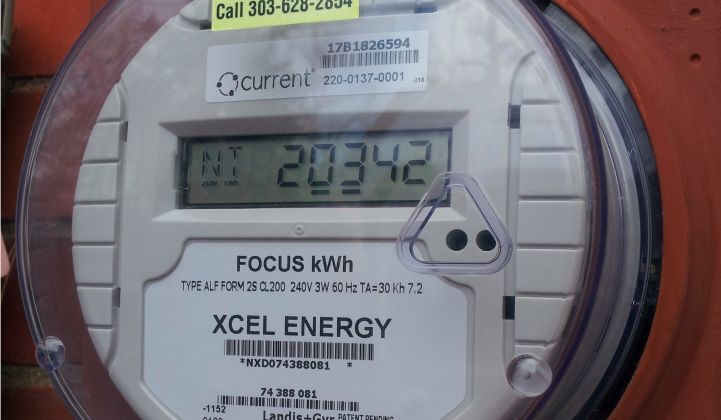

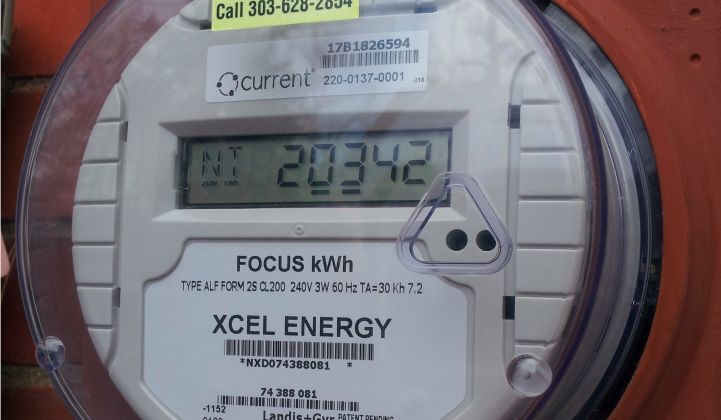

The SmartGridCity smart meters come in several different versions that all look like a standard round, gray electricity meter. The only indication of smartness is a Current logo on the meter. One resident, who declined to be identified for this story, said that when her smart meter was installed in 2008, the technician refused to explain what he was doing and gave her an 800 phone number to call instead.

Randy Huston, Xcel Energy’s Director of IT Infrastructure and Smart Grid, believes that SmartGridCity was completed successfully, but he acknowledged how the company failed to educate its customers.

“Everything we’ve done is in the interest of the customer,” he said. “We’ve just really sucked at explaining that. And I apologize for the language.”

Huston said that because Boulder’s smart grid was one of the first in the country, some of the technologies it used, such as fiber optic communication technology, turned out to be less ideal than hoped. The new two-way communication technology, installing smart meters for less than a quarter of the population and other features almost doubled the project’s cost within a year after it began. As of October 2012, the total costs were pushing $45 million.

The city and community of Boulder put the brakes on Xcel’s SmartGridCity and began an evaluation to take over the pilot as a city-owned municipal utility. Kara Mertz, Boulder’s Environmental Action Project Manager, said that city staff previously offered to help Xcel correspond with the community, but that the utility just had too much on its plate. The smart grid project was operationally successful though, she said.

“I feel like it has a lot of really valuable components to it, it was a good test, but we didn’t interface with the customers as well as we could have,” Mertz said.

Some residents, such as Holger Dick, a University of Colorado Boulder graduate student in computer and cognitive science, might call that an understatement. Dick believes that one of the biggest problems with SmartGridCity is the customer interface.

“I had a smart meter, but I didn’t even know I had a smart meter,” said Dick.

Dick and a team of CU engineers are working on exactly this problem: how to inform people about their electricity use. The team is creating an online system called “EMPIRE” -- EMpowering People In Reducing Energy consumption.

Still in the development phase, EMPIRE uses a smart meter that looks and works like a two-outlet, indoor power strip. Its point, one that Xcel neglected, is to engage consumers in their own energy use.

“For most of us, there are very few forms of energy use that we really value,” Dick said.

In other words, it’s just too easy and mindless to flip the light switch on. The EMPIRE project is just an example of a technology concept that SmartGridCity had, but didn’t use effectively in Boulder. A report released in January by the SmartGrid Consumer Collaborative suggests that this may be because Xcel, an investor-owned utility, views its ratepayers as exactly that: ratepayers. If, in the case of Boulder, the city were to run the utility, its ratepayers would instead be community members, and the focus could shift from profit to lower costs and energy efficiency.

City staff said that if the municipal utility is approved, the decision pertaining to which should be finalized around August 2013, a plan to inform consumers about the smart grid would be put in place to help drive the success of the smart grid.

“If we take over the utility, the concept behind SmartGridCity -- of consumer information, consumer choice, and consumer communication -- would be a huge part of what we would do,” said Sarah Huntley, a City of Boulder communications manager. “It’s one of our fundamental reasons why we want to get involved: to let people know enough about their energy use and be empowered to make choices about how to reduce use.”

Smart Grid

Boulder’s Smart Grid Leaves Citizens in the Dark

Utilities have to engage with consumers and businesses to make the smart grid work.

Boulder’s Smart Grid Leaves Citizens in the Dark

-

41Where Will DOE’s Loan Program Make the Next Climate Tech Investments?

-

15What the Frack Is Happening With Natural Gas Prices?

-

9With an Energy Crisis Brewing, No Peak in Sight for Emissions