In the midst of the longest government shutdown in U.S. history, a rare instance of bipartisan energy policy success mostly got lost in the noise.

President Donald Trump signed a bill into law Monday aimed at accelerating development of a new generation of advanced nuclear reactors. The Republican administration's efforts to revive the coal industry clash with Democrats’ plans to address climate change and transition to clean energy. So this marks a rare instance of cooperation between the two parties, and the second instance of cooperation on advanced nuclear in the last four months.

The Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act calls on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to make its review process "technology-inclusive" by 2028. The process was designed for the light water reactors that ruled the industry for the last half-century, but new reactors emerging from labs and startups use fundamentally different technologies. The law also calls for more transparency on the costs and timelines of NRC reviews.

“It’s really recognizing that a lot of our policies around nuclear and institutions around nuclear are pretty outdated,” said Jessica Lovering, who researches nuclear technology and policy as director of energy at The Breakthrough Institute, an environmental think tank supportive of nuclear power.

The NRC is not affected by the partial shutdown, which has slowed renewable energy permitting and forced hundreds of thousands of federal workers to work without pay. Its budget is funded through fiscal year 2019, according to law firm Morgan Lewis. But even with the office open, the NRC's review process is slow, which the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act seeks to address.

This follows another nuclear assistance law passed with bipartisan support and signed by Trump in September.

The Nuclear Energy Innovation Capabilities Act called for a cost-sharing grant program to help advanced reactors pay for the lengthy licensing process, and construction of a fast neutron source for testing advanced technologies. The U.S. currently lacks such a facility, forcing companies to look overseas to test certain reactor designs.

Big win for advanced reactor advocates

The two laws together knock off several wish-list items for the various stakeholders interested in commercializing advanced reactors.

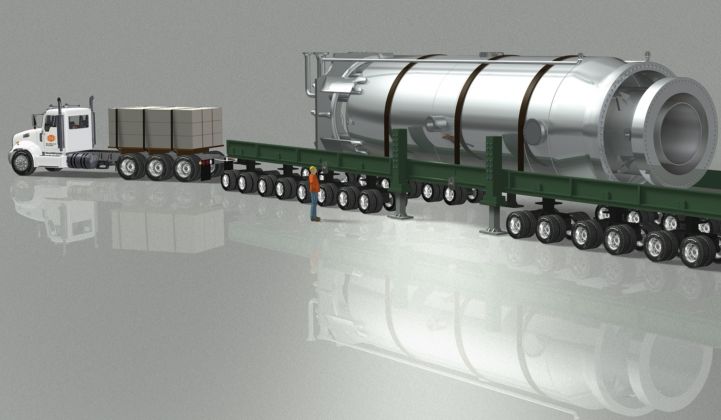

Old-school light water reactor construction has all but vanished from the U.S., thanks to gargantuan construction costs, long build times and public concerns about the technology. New technologies promise an antidote: They’ll be smaller, safer and easier to install, their advocates say.

Interested parties include more than the old-guard nuclear industry itself.

There’s a cluster of new startups entering the space after decades of technological stagnation. A vocal contingent of climate activists insist that nuclear, as the largest source of zero-carbon electricity, will play a crucial role in decarbonizing electricity (others would rather shut it down and put all their chips on wind and solar).

On the more conservative side, nuclear energy represents a reliable 24/7 power source, just the sort of thing the Trump Department of Energy has argued for as a bulwark against the intermittent fluctuations of wind and solar plants.

It’s also the living legacy of American ingenuity, at risk of being co-opted by Russia or China. And it could create jobs as test sites and production move forward.

Time is money

Only one of the new cohort of nuclear companies, NuScale, has officially begun the NRC review process. Tellingly, that company still uses light water reactors, just scaled down small enough to be produced in a factory; it didn’t have to run the gauntlet with a fundamentally exotic reactor design. NuScale also received a cost-share grant from the DOE worth $217 million to help pay for the review, which will take several more years.

The NRC derives most of its funding from fees paid by applicants, Lovering noted. The longer it takes to review a new and unprecedented design, the more the company has to pay for it.

Rewriting the regulations should avoid some headaches by tailoring questions to the new technology, instead of framing the review around what makes sense for light water reactors. Saving time literally saves money.

“There has been stuff happening inside the NRC, but having legislation that directs them to come up with the rules and put them in place, that’s a big change,” Lovering said. “A lot of advanced reactor companies need this to happen before they can start licensing.”

While the NRC is not affected by the government shutdown, the licensing process will still be long and expensive. To address this, the new legislation calls for “predictable and efficient” licensing, which should at least give companies a better sense of how long they should expect to wait.

The two laws set in motion a number of small efforts that could produce more efficient testing of new technologies. That still doesn’t guarantee advanced nuclear will succeed in the marketplace: As an expensive new electricity source, it will have to break into a market increasingly dominated by cheap renewables. Utilities tend to be risk-averse in adopting new energy technologies, and nuclear comes with more public relations challenges than most.

Future legislation could focus on jump-starting demand, Lovering said. Permitting has to come first, though, and Republicans and Democrats agree on that, if little else in the energy arena.

“It’s this rare thing where both sides can come together and agree we should be making it easier for these...American companies to be developing advanced energy technology,” she said.