Utilities are trying to come up with interesting and visible applications for energy storage that will take pressure off their grids and win them a bit of goodwill with the public.

Flow battery startups are trying to find profitable niches for their revolutionary, but long-in-development technology.

And charging station networks are trying to figure out how to reduce the time it takes to charge an electric car from hours to minutes.

Geographically distributed flow batteries might be an answer, suggested Lee Burrows from VantagePoint Venture Partners during a presentation and subsequent conversation at a breakfast held by the SDForum today.

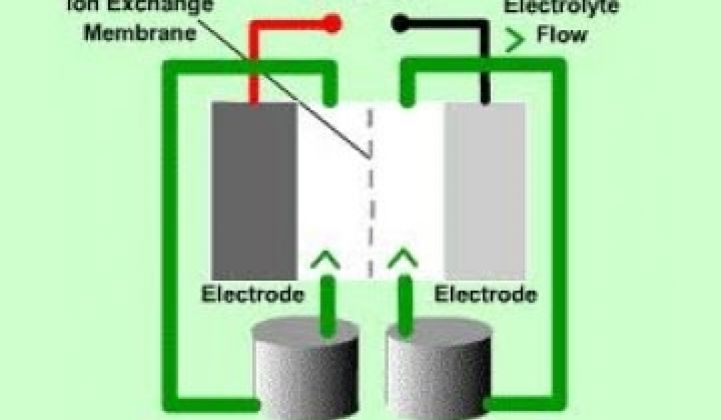

Car owners and charging networks would like to set up 480-volt Level 3 charging stations in urban areas or along freeways, and even large numbers of 240-volt Level 2 stations. Unfortunately, these stations could stress the grid if lots of drivers decide to charge up on a hot afternoon at around the same time. Flow batteries could help solve that problem by taking a steady charge from the grid but holding enough power to charge up several cars in an afternoon, he said. The electrolyte could then be replenished at night. (Flow batteries function like your pulmonary system: charged electrolyte flows in, discharges its valuable particles, and then flows out.)

A decent-sized bank of flow batteries could be fit into shipping containers and parked in the back of a gas station, right near that huge white dumpster near the bathrooms.

It's an interesting idea. Deeya last year came out with its first redox flow batteries. The first units sold for around $4,000 a kilowatt, but the price is dropping. Deeya has mostly positioned its battery as a backup power supply for cell towers: electric cars could bring a needed injection of potential customers to the market. Consumers might be less hostile to them than smart meters, making the idea attractive to utilities.

IBM's Drew Clark added that Big Blue is a big proponent of distributed storage, too.

In other battery news:

--GM and ABB announced they would collaborate on ideas for figuring out what to do with the slightly depleted lithium-ion battery packs from cars. Lithium-ion battery packs can last for years, but only work at their optimum levels for the first few years. Under the scenario that has been proposed by many, car owners could sell their battery packs to a utility, which could then use the battery pack for local grid storage. Ideally, it would reduce the cost of an electric car.

Better Place adds that the battery doesn't even have to be owned by the consumer. Better Place keeps title and rotates new batteries into the transportation fleet and old ones to the grid on its own. (Better Place also believes that drivers can swap batteries when they need a charge, not just when their battery pack is losing a bit of oomph. Most other companies, however, are skeptical that the concept of casual battery swapping will gain steam.)

With this sort of infrequent battery swapping, consumers would also get something they don't get with gas cars: a car that doesn't age very fast.

Nissan and Sumitomo have formed a joint venture called 4R Energy to explore infrequent battery swapping, too.

--And finally, battery maker Ener1 has divided itself internally into three functional units. One will make automotive batteries. One will make battery packs for the grid. And the third will aim at consumer electronics. It remains unclear who will go, "Whee! Whee! Whee!" all the way home.