After years of working in the first-of-a-kind deployment phase, grid energy storage vendors are looking for repeat business.

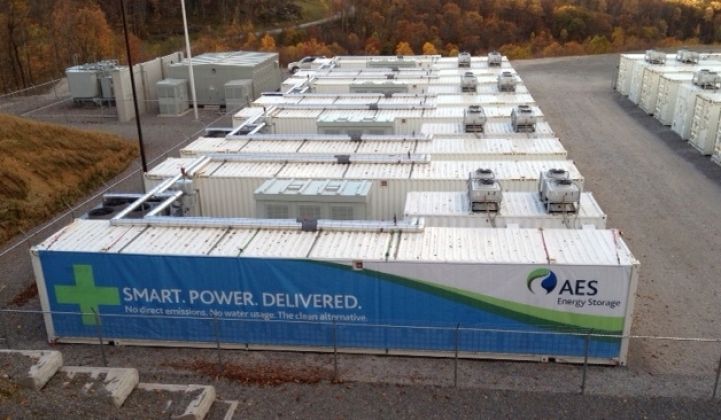

That’s the message coming from AES Energy Storage, which on Thursday announced what it’s calling its Advancion energy storage offering -- a prepackaged, modular system that’s meant to challenge the grid storage status quo. This “fourth-generation” version of its technology combines new core integration partners, new ownership models, and a new business case: replacing gas-fired peaker plants.

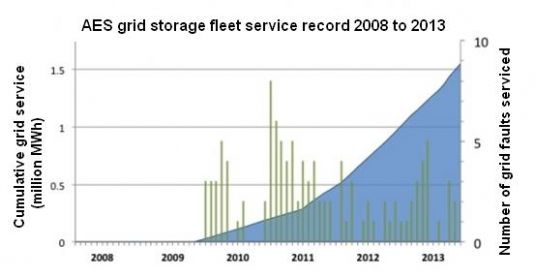

AES Energy Storage is already a leader in battery-based grid storage, with 174 megawatts of systems deployed, and a potential 1,000 megawatts more in development. But in the six years since it initiated its first large-scale grid storage project, the company has refined the way it ties together batteries, inverters, grid electronics and the software that manages their interaction with the grid, according to AES president Chris Shelton.

That work includes the opening of its Battery Integration Center in Indianapolis, where the company has spent the past nine months or so working to certify its first two integration partners, he said. They’re big ones: Korean lithium-ion manufacturer LG Chem, which is supplying the batteries for Southern California Edison’s 32-megawatt Tehachapi wind power storage project as well as for the Chevy Volt, and U.S.-based inverter maker Parker Hannifin.

That list is set to grow in the coming months. “Since then, we’ve introduced new suppliers into the integration center and are working with them right now,” he said. This kind of pre-integration work is critical to moving from a project-engineering approach for each new storage deployment, to something that could be considered a “product,” replicable at different scales for different grid needs, he said.

That includes the flexibility to scale from tens to hundreds of megawatts, and to provide energy durations ranging from thirty minutes to four hours or more, Shelton said. “When we combine that with our control system, we get a great finished product for the grid,” he added.

And, unlike all of AES’ existing storage deployments, its new product can now be owned by a third party. That’s an important step that could help boost sales to renewable energy project developers that want to incorporate the system into the overall project costs, to maximize the return from tax incentives, or to meet emerging requirements for storage-backed solar and wind project emerging for island grids like Puerto Rico and Hawaii.

Finally, Shelton described the company's updated “control system that does the aggregation of the components, as well as the market-facing application logic,” he said. This new iteration of AES’ Storage Operating System already supplies customers with a suite of energy market interfaces for services like frequency regulation, renewable energy smoothing and other storage functions.

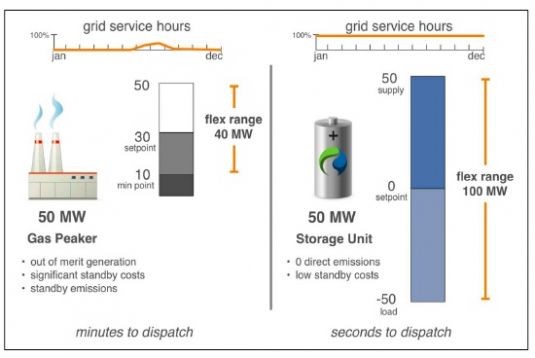

Now, with markets from California and New York to Germany and Italy starting to expand the range of grid services they’re willing to consider for energy storage, AES is explicitly pitching Advancion’s ability to replace gas-fired peaker plants.

Energy storage advocates have been promoting the value of batteries as a peaking resource, noting that they’re able to absorb as well as inject power, and respond much more quickly to changes on the grid.

They’re also far more flexible in terms of scaling to meet grid needs. While peaker plants don’t get much smaller than 50 megawatts or so, battery systems can be deployed in smaller and cheaper increments, then scaled up over time.

In economic terms, Shelton said that its battery systems are targeting a capital cost of $1,000 per kilowatt or less for a deployment built to stand in for a peaker plant. That’s compared to costs of about $1,350 per kilowatt that have been paid to recent gas-fired peaker plant projects in California, he said.

Because peaker plants are procured years ahead of time to prepare for projected grid needs, it’s hard to predict how or when energy storage alternatives will get a chance to bid themselves in as challengers for this role. But there’s little reason to fear that large-scale energy storage projects that provide much faster-acting services like frequency regulation or wind and solar power balancing couldn’t manage the relatively simpler task that peaker plants serve, he said.

In the meantime, “the mandate of folks spending billions of dollars on peaking plants is dependability and cost-effectiveness,” Shelton said.