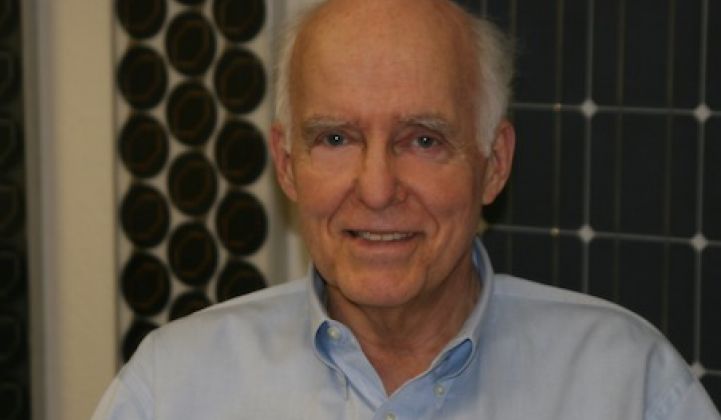

The solar power family lost one of its founding fathers when John W. “Bill” Yerkes passed away on January 29. He was one month shy of his 80th birthday.

I found out about his passing last week when SolarWorld paid tribute to the man. Since then, there has been an astonishing lack of coverage in both the trade and mainstream media, apart from local press. Yerkes and his legacy deserve better. While he may not be a household name to most or included on the short list of technological and industrial pioneers, he should be remembered as one of the vanguards of the solar energy revolution in the United States and the world.

Present at the creation of the U.S. photovoltaics industry during the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the Stanford University engineering graduate joined Spectrolab (then owned by Textron) in 1967, the first U.S. producer of solar cells and panels for space applications. Yerkes served as president-CEO and “oversaw development of the solar array that Apollo 11 left behind on the moon,” according to the Solar World release.

He was fired by Hughes, the new owner of Spectrolab, a move that infuriated him and prompted him to hang out his own solar shingle. Yerkes founded Solar Technology International in 1975, a small, family-and-friend-funded company based in Southern California, which was focused on the nascent terrestrial PV market. During the STI years, Yerkes and his team were responsible for numerous “innovations that transformed the economics of silicon solar cell manufacture,” according to Bob Johnstone in his fascinating, history-rich book, Switching to Solar.

One of those breakthroughs was the development of "a simplified method for printing the silver metal contacts used to interconnect the cells and extract electric current from them” -- the screen-printing technique still used in today’s crystalline silicon PV cell manufacturing lines. In a sense, Yerkes has left his mark on each and every c-Si cell made since those early days.

STI was eventually bought by oil giant Atlantic Richfield and became one of the first iconic brands in the fledgling sector, ARCO Solar. During Yerkes’ tenure running the ARCO PV unit, it became the world's largest solar company, with modules shipped to and deployed in every major region of the globe. The firm was a megawatt-milestone machine, being the first to achieve 1 megawatt of manufacturing capacity, the first to ship over 1 megawatt of product in a year, the first to receive a million-dollar order, and the first to install a grid-tied 1-megawatt system.

Yerkes was always a stickler for quality and reliability, and some of those decades-old ARCO panels fabricated under the solar PV pioneer’s leadership can be found generating tens of watts of power, at or above spec, around the world. The ARCO legacy lives on in SolarWorld, which is the current owner of an organization that was sold by ARCO to Siemens, which sold it to Shell, which then sold it to SolarWorld.

After Yerkes left ARCO in 1985, he continued his life’s mission. He went on to develop “a series of businesses that pushed the boundaries of solar technology,” notes the SolarWorld announcement. “In the mid-1980s, he founded a thin-film startup that made cadmium-telluride solar cells some fifteen years before current industry players got their start. He led the establishment of Boeing’s High Technology Center in Bellevue, WA, which developed gallium-arsenide solar cells and photonics devices, and later served as power systems manager for Teledesic, a startup that produced 1,000 low-Earth-orbit satellites for internet telecommunications. In 2005, he cofounded Solaicx in California and Oregon, where he developed a proprietary high-efficiency, low-cost silicon-crystal-growth technique for solar cells.” (MEMC, which is now SunEdison, bought Solaicx in 2010.)

Yerkes had an eye for spotting technical and business talent, and he hired some of the best minds of the subsequent generation of solar industry leadership. Raju Yenamandra’s career spans the various corporate owners, from his beginnings at ARCO in Camarillo in 1980 to SolarWorld, which currently employs him as VP of business development in the Americas.

“Bill Yerkes was the first big visionary who saw what solar power could do for the world,” Yenamandra said in a statement. “He worked tirelessly to proliferate solar technology by making it widely affordable, driving down the costs not just of solar modules, but of total systems. He prized innovation, efficiency, and the competition of ideas.”

I contacted two other prominent solar leaders, Charlie Gay and Chris Eberspacher, and asked if they would like to contribute some memories of their mentor. Gay was hired as the head of R&D for ARCO, and eventually took over as president once Yerkes left the company. Eberspacher joined the company in 1983 as a young research scientist and went on to lead the R&D team. Both have gone on to technical and executive positions for the likes of Applied Materials, SunPower, Hanwha, Nanosolar and Unisun.

“Bill Yerkes was magical,” writes Gay. “His raw, positive enthusiasm could always be felt and was contagious. Many know that Bill’s engineering contributions to screen-printing and glass lamination, from 40 years ago, laid the foundations for today’s cost-effective photovoltaics manufacturing. Bill was also instrumental in establishing the remote and rural markets for solar electrification. Nothing better conveys the lengths to which he stretched than is apparent in the following story.

“The year was 1978. ARCO had entered the PV business as a result of the second oil shock and, after screening many candidates, acquired Bill’s company: Solar Technology International. To further accelerate the R&D program, ARCO invested in thin-film PV materials, including amorphous silicon with Energy Conversion Devices (ECD) in Detroit. ECD was founded by Stan and Iris Ovshinsky, and among the many luminaries consulting at ECD was a brilliant MIT professor and physicist, Dave Adler. Over the span of twenty years, Adler published nearly 300 technical papers described as ‘among the clearest and best written in any field of science and technology.’”

“Adler was also known for his love of world travel,” Gay continues. “At the evening dinner celebrating the first contract between ARCO and ECD, Dave stood and recounted his summer vacation. He told of seeking an adventure to the most remote, primal area possible to see what was regarded as the last remnants of Stone Age village life on earth. The destination was a remote corner of Papua New Guinea, which only saw its first European about 100 years prior to Adler’s visit. The journey began at Port Moresby on the southeastern coast of the Papuan Peninsula of the island of New Guinea. The city had been a strategic target in World War II for isolating Australia from Southeast Asia and the Americas.

“Adler reached Port Moresby from Brisbane on Air Niugini. From there, the story unfolds almost like a reprise of Apocalypse Now. Day by day, the world became stranger and stranger. First, there was a two-day jarring and gut-turning jeep ride over rutted dirt roads. This was followed by two days on horseback. Then, three days paddling a canoe progressively farther upriver to a region where people still used volcanic sulfur and ash to emblazon tattoo chest markings related to their headhunting exploits. As Dave at long last approached the ultimate destination village, he could see children scrambling into the water to swim up in greeting. As the kids emerged from the water, pulling themselves up on the gunnels, every child was proudly wearing a blue ARCO Solar T-shirt.

“Papua New Guinea was the first large market for PV-powered remote telecommunications systems. Yerkes’ business briefcase was emblazoned with an Air Niugini sticker for over half a decade, as a testament to the campaign. The region created the first growth market for solar after navigation aids, and, because of its climatic extremes, it was important to refining and validating the design for reliable, low-cost solar. Dave could only say that, when he met those children in New Guinea, he then knew solar would ultimately touch everyone’s lives. He was excited to contribute his part.

“Bill’s passion and inspiration live on in thousands of us and in every watt of the over 100 billion watts of solar powering the world today,” Gay concludes.

Eberspacher recounts that he “first met Bill Yerkes when I interviewed for a job at ARCO Solar in 1983. He sauntered into the office where I was nervously talking with my prospective second-level supervisor and immediately interjected with a friendly greeting and sincere enthusiasm in response to my lengthy description of my Ph.D. research and how I thought it might apply to ARCO Solar’s business prospects.

“In hindsight, I vastly overestimated that day how quickly technology might make its way from university lab demonstration to cost-effective industrial manufacturing,” he adds. “But Bill -- even though I am sure looking back that he knew from experience that the road was a long one -- was then, and on many occasions following, positive, energetic, supportive and enthusiastic, so much so that he instilled and/or reinforced in others a sense of vision, purpose and confidence in the PV industry and its power to deliver real and lasting value to the world. Yerkes was one of the key founders and contributors to the modern PV industry.”

Bill Yerkes is survived by his wife Sara, who lives in Santa Barbara, and his daughter and son-in-law, Kari and Jean Hummel, who reside in the Bay Area. Bill’s first wife, Irene Yerkes, lives in Los Angeles.

***

Thanks to Devon Cichoski of SolarWorld, Charlie Gay, and Chris Eberspacher for their contributions. Additional background information came from video interviews with Bill Yerkes that are included in the multidisc collection Cherry Hill Revisited -- An Historical Remembrance: The Beginning of the U.S. PV Revolution, which Larry “Kaz” Kazmerski graciously provided to me a few years ago.

Tom Cheyney is the director of Impress Labs' solar practice and the chief curator at Solarcurator.com. This piece was originally published at Solar Curator and was reprinted with permission.