When Florida Gov. Rick Scott told residents “you need to go right now,” as Hurricane Irma barreled toward the state, many were able to jump in their cars and leave. An estimated 3 million people took to the highways, creating hours-long bottlenecks that stretched six-hour drives into 17-hour odysseys.

If all those Floridians drove Teslas, though, it would have been even more difficult. While electric cars can present some grid service opportunities when the power is out, an electrified future will add serious logistical challenges to the already complicated dance of mass evacuation.

In a recent report, researchers at the Universities of Oxford, Michigan and Vermont looked at how EVs would fare in a storm in the Florida Keys. The results are concerning, but not entirely surprising. According to the researchers, government at every level leaves electric cars out of disaster planning.

Problems surrounding emergency management and EVs largely relate to infrastructure. With more residents relying on cars fueled by electricity, the issue of inadequate charging stations will become even more pronounced. The report cites an estimate of 1 million electric cars on U.S. roads by 2020. This year America logs only 15,943 public charging stations with 42,550 outlets -- and not all cars accept the same chargers.

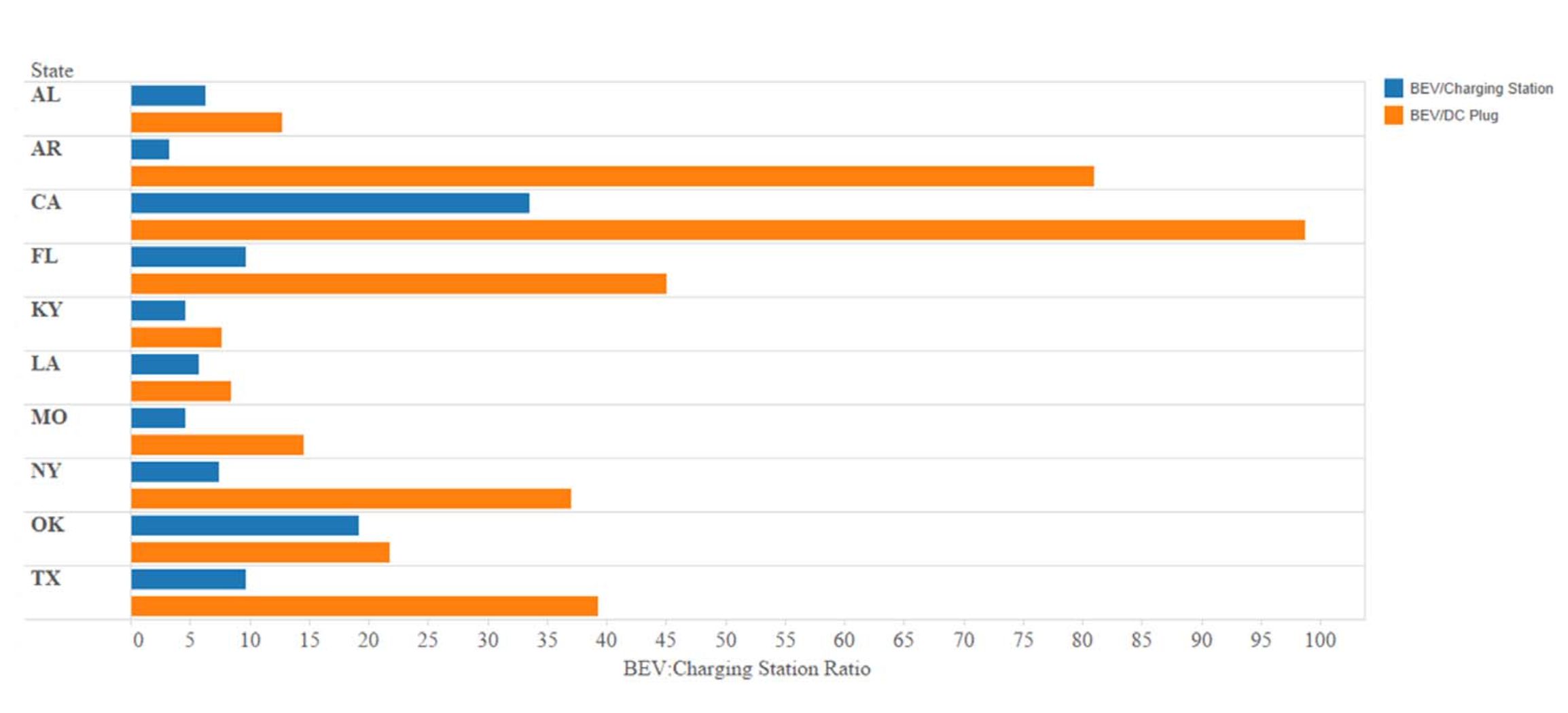

In a disaster zone, the most viable charging option will likely be DC fast chargers, the most expensive type, which can juice up a car with an 81-mile range in half an hour. According to GTM Research, the U.S. had only 4,134 such chargers in 2016. The state with the highest density of DC chargers per car, Kentucky, has one per 7.73 cars (more due to a lack of EVs than a glut of chargers). California, the state with the least, has one charger per 9,285 cars.

Source: Energy Policy/Adderly, Manukian, Sullivan, Son

California lays claim to the country’s most developed EV market and the most chargers of any state. But already drivers there report altercations over access to charging stations. With a hurricane (or, more likely, a wildfire) on the way, expect an escalation of what the director of a San Francisco EV-nonprofit called the “electric vehicle etiquette problem.”

Beyond the sheer number of chargers, disaster-prone states also need to consider the distance at which they’re sited. As the report authors note, even if EV drivers have their cars fully charged prior to an evacuation, it’s unlikely they can make the full journey without recharging. The evacuation scenario amplifies range anxiety and charging speed concerns.

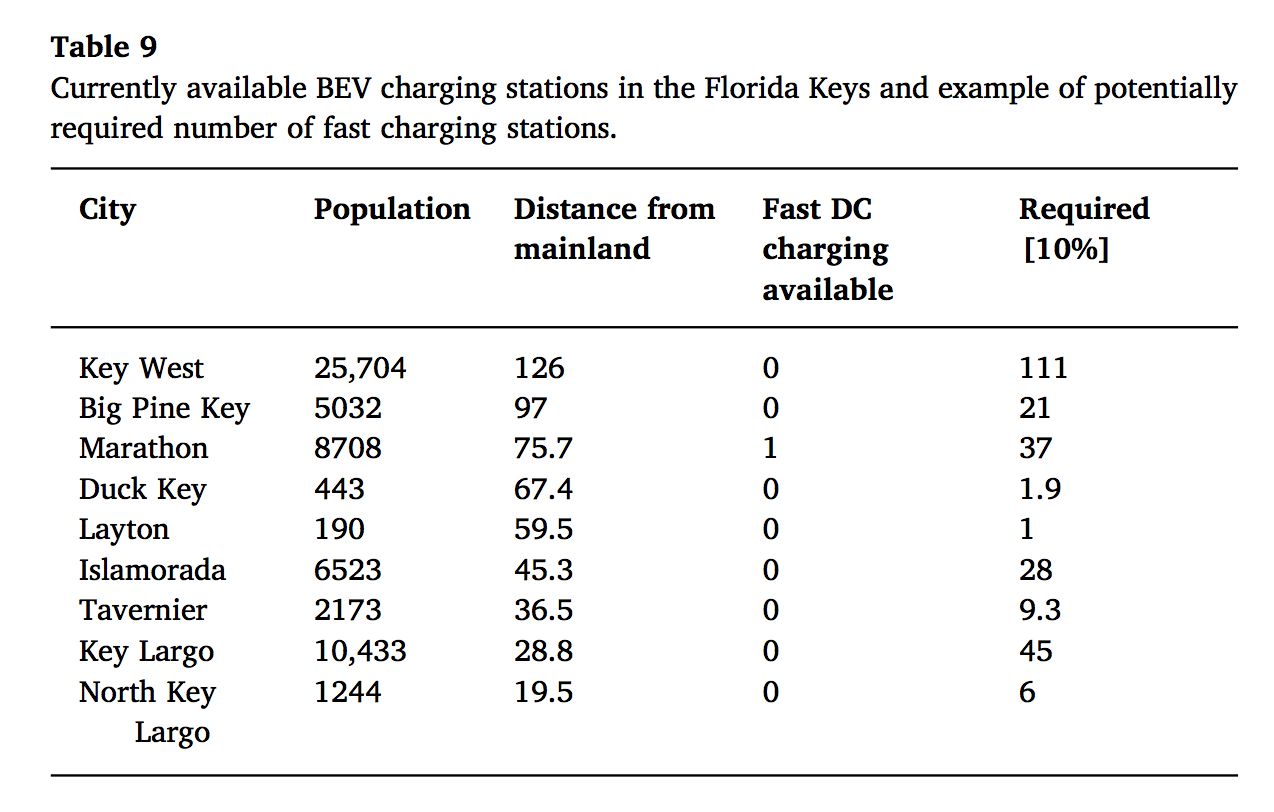

In the Florida Keys, just one DC charge point on the island of Marathon stands between the picturesque isles and the first major mainland city of Homestead. The report estimates that eventually 10 percent of Keys residents will own EVs, amounting to a total of 2,570 vehicles on Key West alone. The analysis found that to charge Key West's cars in a hurry would require 111 chargers. Researchers calculated the distance allowable between those chargers -- using minimum range, weather, and speed of travel -- at just 38.44 miles.

The reports authors assert that “there are substantially fewer charging stations in place than are needed” -- a generous way of saying that the islands are woefully unprepared as EV adoption scales.

Source: Energy Policy/Adderly, Manukian, Sullivan, Son

The situation becomes more complicated considering how the rush to charge vehicles at once could impact the grid.

Prior to Hurricane Irma arriving in Florida, some gas stations in Tallahassee and even in Georgia ran out of fuel, 40 percent of Miami and West Palm Beach stations ran dry, and 58 percent of Gainesville’s stations ran out.

“The system was not built for such insatiable demand all at once,” GasBuddy petroleum analyst Patrick DeHaan told USA Today.

The same goes for the electric system.

GTM Research consultant Timotej Gavrilovic wrote in a 2016 report that so far “EVs have had a negligible impact on overall load,” accounting for just 0.04 percent of national load in 2015. But Gavrilovic found that by 2025, EVs could account for 3 percent of load in areas serviced by Pacific Gas & Electric and Southern California Edison.

As EV adoption increases and weather-related disasters surge, utilities will need to invest in additional infrastructure to ensure reliability during an emergency that peaks demand.

But looking beyond those barriers, EVs can also be a boon in disaster. States and cities have already begun to recognize the potential grid benefits of electric cars. In several new microgrid projects in cities such as Boston and Berkeley, EVs are a key resource. As vehicle-to-grid technology matures, EVs can be used as a backup source during emergency.

Many of the problems related to disaster-management are acute versions of the infrastructural issues already facing EVs.

“Whether EVs will become a grid resource or a strain on the grid will depend on how well these barriers are removed,” Gavrilovic writes.