Greece this month announced a sell-off of about 40 percent of its coal-fired generation capacity in a move intended to help open its electricity market.

But finding a buyer, which Reuters reports will have to be “a European operator to safeguard energy supply security both for Greece and the European Union,” might be a problem because coal is going out of fashion in Europe.

On April 21, for example, the U.K.’s electricity system made headlines after running for an entire day without any coal-fired generation, something that had not happened since the 1800s.

“To have the first working day without coal since the start of the industrial revolution is a watershed moment in how our energy system is changing,” Cordi O’Hara, director of U.K. system operator National Grid, told the Financial Times.

The U.K. was the first country in the world to use coal for electricity and just two years ago the fuel accounted for 23 percent of total electricity generation, the report said. Last year the level dropped to just 9 percent.

And the U.K. is not the only European nation turning its back on the black rock. Last month, in what was termed “a historic pledge,” the dominant electricity firms from all E.U. nations except Poland and Greece pledged to cease building new coal-fired plants from 2020.

The announcement, issued by the European electric utility body Eurelectric, which represents 3,500 companies across the continent, was pitched as being in aid of the fight against climate change.

“The power sector is determined to lead the energy transition and back our commitment to the low-carbon economy with concrete action,” said Eurelectric president António Mexia in a press release.

But the reality is that, as in U.S., coal in Europe is already dying a slow death because of economics. In many countries, an increasing proportion of renewable energy on the grid is edging coal and lignite out of the market.

This summer In the U.K, for example, National Grid may be forced to pay coal plants to stay shut, and even provide incentives for large power users to up their consumption, to prevent the grid from being overwhelmed by an influx of solar and wind energy.

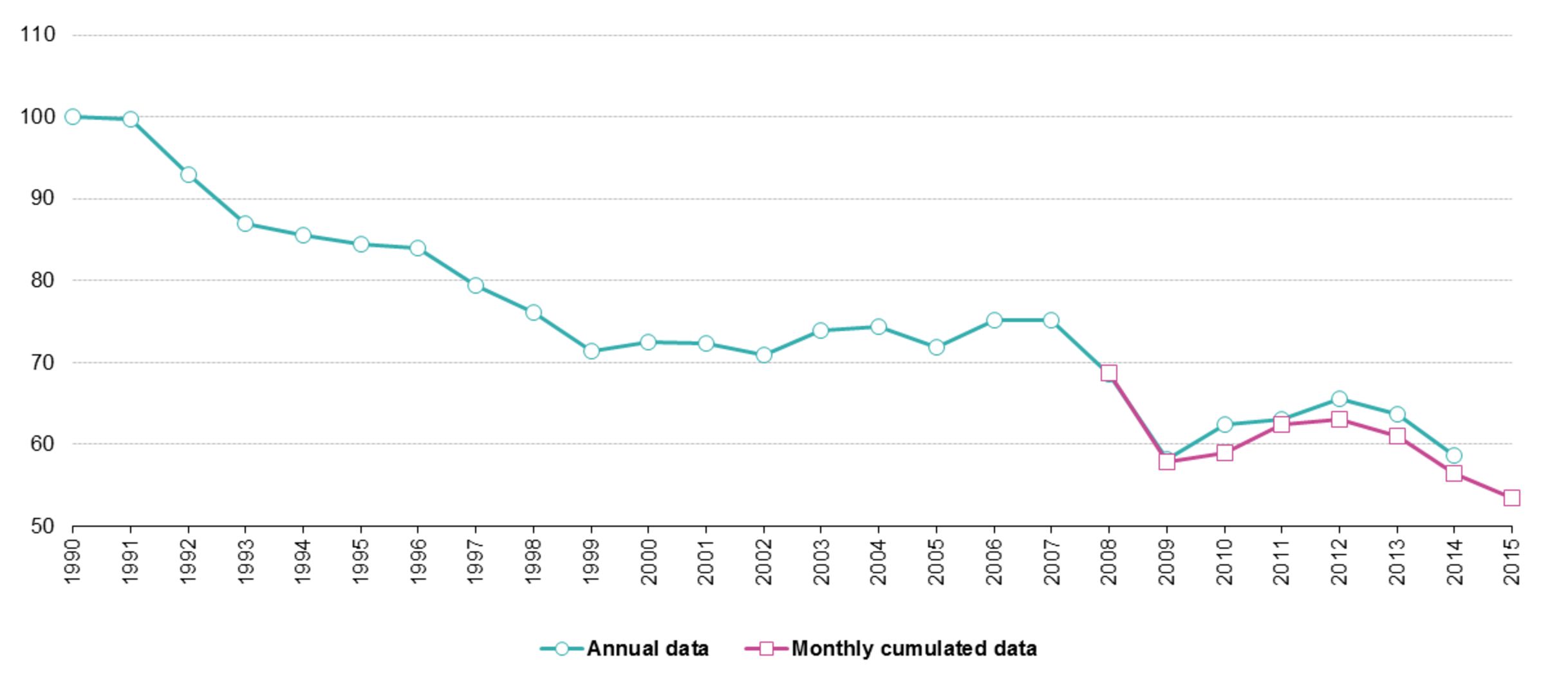

Across Europe, data from the European Commission statistics agency Eurostat shows coal consumption has halved in the last 25 years.

FIGURE: EU-28 Gross Inland Consumption of Hard Coal, 1990-2015

Source: Eurostat

“In 2015, gross inland consumption of hard coal in the E.U.-28 reached its lowest level at 269 megatonnes, 47 percent less than in 1990,” says the agency.

Against this backdrop, promising not to build any more coal plants after 2020 does not seem like a big deal. There probably won’t be any call for them anyway.

And longer term, said Valts Grintals, analyst at Delta Energy & Environment (Delta-ee): “We see coal being phased out as a very likely scenario.”

Such a prospect might cheer climate campaigners, but it raises a question for policymakers and grid operators: what should take coal’s place? In most European nations, coal has a valuable role in providing baseload generation.

In this respect, it is like nuclear energy, which does most of the electrical system heavy lifting in countries such as France, Slovakia or Belgium. But nuclear, too, faces an uncertain future in Europe, once again because intermittent renewables seem a cheaper and easier choice.

With coal fading away and new nuclear out of the picture, “you’ve got a number of options, but there’s no silver bullet,” said Delta-ee principal analyst Scott Dwyer.

There's renewable energy, of course, bolstered by a mix of district heating, demand-side measures, capacity management and storage to help overcome the intermittency.

Yet although “the coal phase out is clearly great news for storage,” said Nick Butlin, managing director of London-based consultancy Viriya Energy, there are concerns over how much stored energy would be needed to tide Europe over long-term periods of calm, cloudy weather.

And “you'll likely still need gas in some form to help with the de-carbonization of heat," Dwyer said. “The question is how much will be centralized, in combined cycle gas turbine power plants, or de-centralized, such as combined heat and power or gas heat pumps.”

Given the uncertainties, Hugh Sharman, principal at Aalborg, Denmark-based consultancy Incoteco, said what is really needed is a “magic wand, maybe?”

Thankfully, Europe has time to find it. Despite coal’s declining popularity across the continent, the E.U. remains the world’s fourth-largest consumer of the fossil fuel, after China, India and North America.

And coal accounted for 26 percent of all power generation across the E.U. in 2014, according to figures from the European Association for Coal and Lignite. Coal may be on its way out, but its flame looks set to burn for some time to come.