There is a growing gap between the infrastructure we need and the infrastructure we have.

For two decades, Wedbush attorney, investment banker, and water industry executive Michael George has watched “the way we think about, use, finance water infrastructure and now the nexus between potable water, wastewater and energy.” It has, he said, “changed -- not necessarily for the better -- recently.”

The same could be said of energy and the way it is delivered.

Knowing that its service is “critical to human health and happiness,” the water industry has embraced a regulatory structure that ensures consumers are getting water that is not only safe but healthful.” This, George noted, comes at a cost. And “the question of how that is going to be paid for has been deferred,” he said.

Because the resources used to generate electricity impact the air, water and environment, energy industry regulators, in a way very similar to what George described in the water sector, have embraced stiffer controls on traditional fuels and established renewables mandates without serious consideration of cost.

Early on, the federal government led the way with clean water standards and provided ways to pay to meet them, George said. “You had significant federal grants and financing mechanisms for water, wastewater and the energy required to provide them.”

This became a long-term structural dilemma when demand for new infrastructure advanced ahead of the capability to pay for it, he said.

The current budget crises at the federal, state and local levels present a further short-term cyclical dilemma, George said, while the push for healthier water continues, the tax support available for healthier water is reduced, and the generational need to replace aging infrastructure grows.

The result, he said, are projections from various responsible federal and state agencies that need new infrastructure that will cost “an order of magnitude beyond our ability to finance them in traditional ways.”

In the energy arena, private power producers and public and private utilities are all players in a long-term structural dilemma very like the one George described in water.

They may once have had the capacity to fund the retrofitting of traditional generating facilities and the building of new traditional and renewables infrastructure -- supported by federal, state and local tax incentives and rebates. But a growing need for renewables like wind and solar and new transmission infrastructure has raised demand for new energy infrastructure faster than the willingness to fund it has grown.

Congress has begun dismantling incentive provisions that once supported the building of energy infrastructure. In doing this, lawmakers have exacerbated the long-term structural dilemma by adding a short-term cyclical response.

Due to regulatory requirements, George said, water enforcement agencies bring protective lawsuits and “projects get done at the point of the litigation sword” instead of “in the overall cost-benefit context.”

Similar inefficiencies are found in the energy sector. In response to federal agency litigation, utilities retrofit old power plants instead of investing in new renewables and new transmission.

There are, George said, ways to bridge the gap between what there is and what is needed. In water, he said, “conservation is always first.”

That is just as true in the energy sector, where negawatts are cheaper than megawatts.

Another part of the solution is, George said, to build new infrastructure to supplement existing “heritage infrastructure” wherever possible. An example would be directing desalinated water to coast-adjacent populations.

In the energy sector, this means more distributed generation that serves local needs without new transmission.

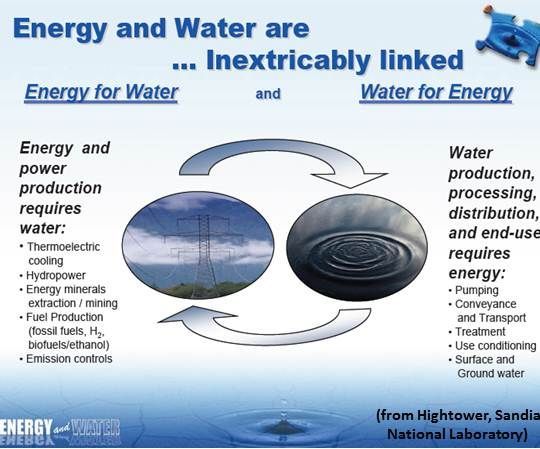

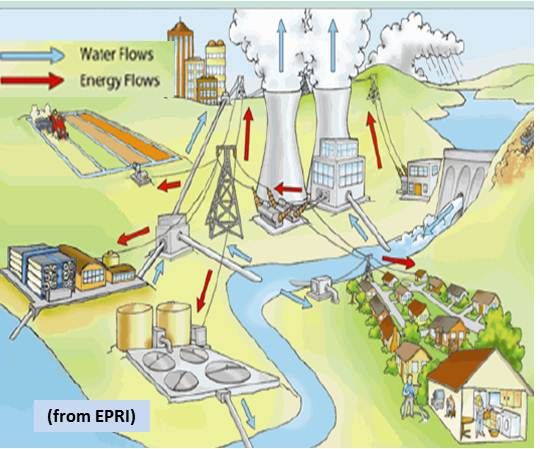

The need for new water infrastructure can also be reduced by the efficient recycling of water (formerly known as wastewater treatment). This would also reduce the need for the energy to drive such processes.

The biggest part of the solution for closing the infrastructure gap, George said, is “to empower pools of private capital to come in to fill some portion of this gap.”

Public agencies in the water business have long financed projects through municipal bonds and grant funding. But the capital needed for new infrastructure is now greater that what can be met by municipal bonds or grant funding, George said. Yet the “machinations” necessary to bring in private capital and combine funding sources are prohibitively complex. The gap is the result.

A similar regulatory complexity, designed to protect taxpayers, prevents public water agencies in procuring from the private sector, George said.

The ultimate solution, therefore, are regulatory fixes that streamline the processes to marry traditional public mechanisms and private investment and resources.

Renewables were given the very solution George prescribed in the set of tax credits and cash grant provisions made available in the Recovery Act. The expansion of 2009 and 2010, especially in wind and solar, was the result.

The current Congress appears to be set on dismantling many of those provisions. Prepare for an energy gap.