Community wind pioneer OwnEnergy just got more backing from New Jersey Resources Clean Energy Ventures (NJR CEV), a fully owned subsidiary of gas utility New Jersey Resources (NYSE:NJR).

This could take mid-scale wind development to a new level.

“OwnEnergy’s midsize projects,” explained CEO Jacob Susman, “are about a third to a quarter the size of what’s typical in the wind business.” Building smaller is an emerging, successful strategy used by renewables developers to push projects past the obstacles that can impede utility-scale development.

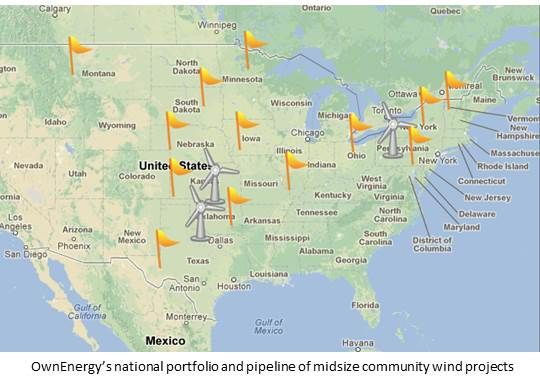

OwnEnergy is possibly the first developer to build a national identity in the midsize project space, although some community wind developers, like South Dakota Wind Partners, juwi Wind, Juhl Wind, and First Wind have regional brands. REC Solar is beginning to build community solar projects nationally, and regionally identified developers like Silverado Power and Mosaic are emerging.

OwnEnergy, founded in 2007, has used what Susman called a capital-light approach to put three projects totaling 140 megawatts in operation and has about 1,000 megawatts in its twenty project pipeline across fifteen states.

Community-sized projects are typically between one and twenty megawatts, Susman said. What makes OwnEnergy’s average 50-megawatt developments more aptly labeled "community" than "small utility-scale" is that they always partner with a local.

“Our approach is to find tuck-in opportunities in regions across the country where others have been doing large-scale development,” Susman said. “If you tuck in a midsize project, you can get a good return. But what drives our strategy is the local partner model.”

The local partner is a well-established member of the community who becomes the face and voice of the project during the earliest stage of development when a renewables project is most likely to encounter potentially insurmountable local opposition.

“That’s the stage where big out-of-town energy companies tend to do badly and local folks do really well,” Susman said.

“It’s one thing for a stranger from Brooklyn to come in and another for a friend and neighbor to ask for land leases and set-back waivers,” explained Marty Yahner, a sixth-generation western Pennsylvania farmer and OwnEnergy’s partner in the now on-line 30-megawatt Patton Wind Farm. “It means something when I ask somebody to sign an agreement I am myself signing and an agreement that, if it doesn’t work out, they can come back at me about.”

When Yahner convinced friends and neighbors the Patton project would bring economic benefits to their community, he was able to get more than twenty legal agreements from previously reluctant locals who are now earning royalties and seeing jobs and businesses grow around them.

OwnEnergy’s average budget to fully develop a project is about $1 million, Susman said. The company asks its local partner, a co-owner in a formal joint venture, for about 5 percent. “We want them to have skin in the game, but we don’t need them to make a huge contribution,” Susman said. “It is typically about enough to pay for the meteorological tower.” The partner’s sweat equity earns them a more than 5 percent share of the project, Susman added.

“Everything besides community relations, the permitting, interconnection and land lease legalities, is the middle stage of development,” Susman said. “That’s when OwnEnergy comes in. It carries the project through the late stage of development, getting the power purchase agreement, contracting for turbines, and arranging pre-construction.”

Though not part of the company’s original business model, the high cost of capital in the post-financial crisis marketplace made it necessary for OwnEnergy to sell the three projects it has brought on-line to larger developers in the last stage of development.

Before the financial crisis, the company put its cost of capital from tax equity investors at about 6 percent, Susman explained. At present, that cost can be 9 percent or more, depending on the price of power and the wind resource.

“The difference between a high cost of capital and a low cost of capital could easily be $5 per megawatt-hour,” Susman said, which can be enough to make it prohibitive for a smaller company to compete against large developers like NextEra Energy (NYSE:NEE), MidAmerican Energy (NYSE:BRK.A) and Duke Energy (NYSE:DUK).

“They are unregulated subsidiaries of utility holding companies,” he explained. They can use all the tax credits in-house or, if they choose to, can borrow at the corporate level from a bank or the bond market at a low capital cost to finance.

NJR, NJR CEV’s parent, is a publicly traded Fortune 1000 utility with an appetite for tax credits and, if it so chooses, could exercise its option to invest up to $400 million off its balance sheet over the next four years into OwnEnergy wind projects.

“Another thing about the NJR CEV investment is that its parent company is a gas company,” Susman added. “We need lots of gas and wind to replace old, dirty coal plants and this is one of the first natural gas pure-plays to invest in wind and one of the first pairings of gas and wind of its kind.”

OwnEnergy plans to build a 2,500-megawatt annual pipeline by 2015, Susman said, and to put 250 megawatts of wind on-line per year.