Not all kilowatts are created equal. In its simplest form, that’s the chief argument put forward by demand-response advocates.

Demand response enables grid operators and electric utilities to relieve stress on the electrical grid by compensating commercial and industrial customers, and to an increasing extent, residential customers, for curtailing electricity use at times of peak demand or in the event of an emergency.

According to a new report published by Advanced Energy Economy, these avoided kilowatts can significantly reduce costs to ratepayers and facilitate compliance with the EPA’s Clean Power Plan.

Approximately 10 percent of U.S. electric system capacity is built to meet demand in just 1 percent of the hours during the year. Procuring demand-response resources reduces the need to invest in expensive new capacity, which saves consumers money.

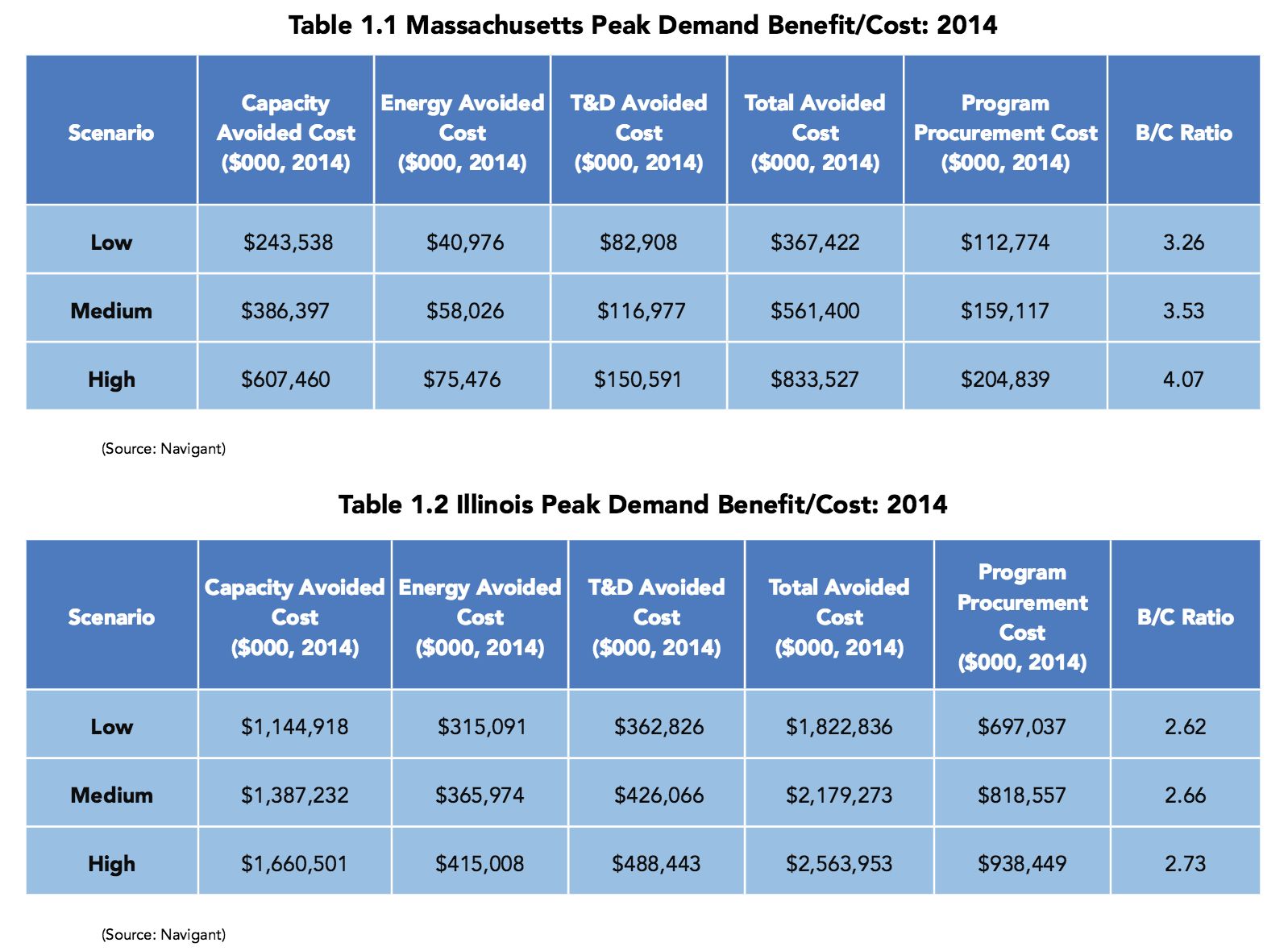

The report, prepared by Navigant Consulting, finds that for every $1 spent on reducing peak demand, ratepayers in Illinois can save at least $2.62, and ratepayers in Massachusetts can save at least $3.26.

The calculation assumes that the peak load in both states does not increase over the next 10 years. If the peak load is reduced by 0.25 percent per year over 10 years in the medium scenario, and 0.50 percent per year over 10 years in the high scenario, the savings are even greater.

Avoided energy use not only saves money, but also translates to avoided emissions. Therefore, by creating peak-demand reduction programs or passing peak-demand reduction mandates, states can mitigate the cost of compliance with the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, the report argues.

However, these benefits are predicated on the participation of demand response in wholesale markets, the authors write.

Last week, the Supreme Court heard arguments on the implementation of demand response in wholesale markets. At the center of the case is FERC Order 745, which calls for grid operators to compensate demand-response resources in real-time and day-ahead markets at the full market price -- the same price paid to new electricity generation.

The Electric Power Supply Association, which includes a number of generators and marketers of electricity, argues that FERC is not authorized to set demand-response prices, or to order wholesale market operators to compensate retail customers for reducing their demand. EPSA and its allied trade groups, including the Edison Electric Institute, argue that individual states should have full control of establishing demand-response payments.

In May, a D.C. Circuit court ruled in favor of EPSA’s argument. According to a FERC brief, the decision essentially bars demand response from participating in wholesale markets. That decision is now under appeal.

Wholesale markets governed by FERC Order 745 represent a small portion of the overall demand response market; most revenue is generated in states’ capacity markets, which are not directly affected by the case. But demand-response advocates are concerned that a decision to change FERC’s responsibilities in this Supreme Court case could trigger a battle in capacity markets too.

According to Advanced Energy Economy, which represents demand-response providers such as EnerNOC and Opower, changing the rules on demand response will significantly reduce customer savings.

“It’s incredibly important for FERC Order 745 to be upheld, because that’s the way that demand-response programs are going to see the greatest number of benefits and the greatest amount of avoided costs,” said J.R. Tolbert, senior director of state policy for Advanced Energy Economy.

The report lists several ways that peak demand reduction interacts with wholesale markets.

“The two main avenues to reduce wholesale capacity charges through peak-demand reduction are shifting capacity-cost allocation and reducing the installed capacity requirement. Transmission is another wholesale cost that may be reduced by a peak load reduction. Transmission is typically a much smaller charge than capacity, but in regions with transmission constraints, like New England, it constitutes a growing portion of the overall bill. Similar to capacity, there are two means to reduce transmission charges: direct load reductions and non-transmission alternatives.”

While the Supreme Court case is not the only factor driving the adoption of state demand-response programs, it has created a degree of uncertainty that could cause state policymakers to hesitate.

Current policies in Illinois allow demand response to play in a wholesale market structure, and encourage demand reduction as part of broader energy-efficiency measures. But Illinois policymakers -- who are currently considering comprehensive energy reforms -- have yet to create a meaningful standard for demand response.

Massachusetts is also on the cusp of making major energy-sector reforms. Later this month, the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities will receive final three-year energy-efficiency plans from the state’s investor-owned utilities. These plans, subject to regulatory approval, will determine the size and design of Commonwealth’s demand-response market into the future.

“[The AEE report] shows that reducing peak demand is a key strategy to meeting New England’s energy and environmental goals,” said Janet Gail Besser, vice president of policy and government affairs for the New England Clean Energy Council. “NECEC urges policymakers and regulators throughout the region to encourage utilities to make use of demand response and other peak-demand reduction strategies to further reduce costs for all customers and strengthen the reliability of the electric grid.”

“Regardless of what happens at the Supreme Court, states should not turn their back on demand response,” said AEE's Tolbert. “Demand response is a key component of energy planning as all states move forward. However, a court ruling that affirms that demand response can participate in wholesale markets is the best structure for realizing the full potential and benefits of demand-response programs.”