Yet again, the Los Angeles Times has published a hit piece on renewable energy masquerading as journalism in a front page article from Friday, “Taxpayers, Ratepayers Will Fund California Solar Plants."

The article cites a Stanford economist for the conclusion that contracts for new large-scale solar projects are locked in at prices three to four times the market price of power: "But outside experts, including Wolak, the Stanford economist, estimate that Ivanpah power (a large solar project currently under construction) is priced at $90 to $130 per megawatt-hour -- three to four times the cost of electricity in the state last year."

This is a highly misleading apples-to-oranges comparison, and Wolak should know better. Spot market power prices are indeed quite low at this point, but that is not the appropriate comparison. Spot market prices are by definition short-term, very different than the long-term market that includes solar power contracts.

Very few energy plants (renewable or conventional) are built to serve the spot market. The point of a long-term contract for power is that it's secure power, and utilities enter into long-term contracts because they can then rely on that power for many years to come, as they are required to do by various state law and policies regarding long-term power procurement (see, for example, the Long-Term Power Procurement proceeding, R.12-03-014, at the CPUC). Long-term contracts are commonly entered into for conventional generation, as well as renewable energy.

The bottom line is that the contracts that the LA Times article derides as “three to four times” the price of market power are in fact at or below the long-term market price of electricity from status quo natural gas power plants. The state's Market Price Referent (MPR) structure is the former methodology for determining whether renewable energy contracts are cost-effective or not, and it applies to the BrightSource Ivanpah contract because that contract was entered into under this methodology. The MPR is the calculated cost of power from a new 500-megawatt natural gas plant. The 2012 MPR for a 25-year contract is $0.09274 per kilowatt-hour, down about 15 percent from the last (2009) MPR table due to declining natural gas prices.

The exact pricing for BrightSource and other long-term renewable energy contracts is not public, and this figure should be public -- that much I agree with in the article. However, the CPUC, at the behest of the utilities and ratepayer advocacy groups like the Division of Ratepayer Advocates (DRA) and TURN, insist that contract prices be secret for three years in order to avoid having project developers simply bid values around known prices rather than the lowest prices they can bid and still have a viable project. I disagree with this conclusion, but it is the rule at this point.

Even though the exact prices are confidential, the approved contracts include a statement as to whether the contract is above or below the MPR. BrightSource's contract as approved by the CPUC would not exceed the MPR, and is thus, by definition, cost-effective.

The 2009 CPUC resolution approving the PPA states: "Based on expected online dates of 2012 and 2013 for 25-year contracts, the expected levelized price for the projects do not exceed the 2008 MPR. The MPR is used by the Commission to evaluate the reasonableness of prices of long-term PPAs for RPS-eligible generation." (I explain the term “levelized” below.)

The MPR value used to determine cost-effectiveness for the BrightSource contract is higher than today's MPR values because the price of natural gas has come down so much. However, hindsight is 20/20, and there was no way in 2008 to know that natural gas prices would come down so much -- as opposed to the vertiginous rise we’d seen up until 2008 (remember that oil hit record highs of $147 a barrel and natural gas over $13 in 2008?). This is the nature of the beast in long-term contracting and critics who complain about how prices are so much lower today than in 2008 are being disingenuous or don't know the facts about the background of long-term contracting.

The article also paints with an overly broad brush in criticizing the BrightSource project. I'm not a big fan of large-scale desert-based solar projects (I have no financial interest in or connection to the BrightSource or other large-scale solar projects) and the transmission required to bring them on-line. I'm a proponent of "community-scale" solar projects that don't require new transmission lines and can be located close to load (also known as "wholesale distributed generation"). However, the criticisms the article levels against BrightSource will surely bleed over onto solar in general -- and entirely unjustifiably.

Only very large renewable energy projects are able to obtain federal loan guarantees. The only incentives generally available for medium and smaller-scale commercial solar projects are the 30 percent investment tax credit and accelerated depreciation. (These incentives are, by the way, far less valuable than the incentives available to new nuclear plants, which include a ten-year production tax credit, Price-Anderson risk insurance, accelerated depreciation, federal loan guarantees and others; I wish the LA Times or the New York Times would do a follow-up looking at the incentives for nuclear plants, and I’ve urged both papers to do so, to no avail as of yet).

Broader pricing issues for renewables

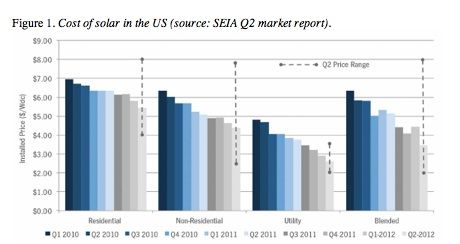

Now let’s look at the cost trends in solar over the last couple of years, to get an idea of the real cost situation and where we’re likely to go in the future. The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) puts out a quarterly report on cost and installation trends in the U.S. Here’s their latest cost chart, through the second quarter of 2012, showing a remarkable 45 percent to 50 percent drop in cost for utility-scale solar (the segment BrightSource belongs in, as well as the community scale solar segment) since the start of 2010:

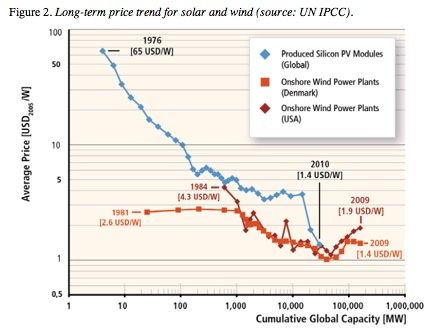

What about the longer-term trend? Well, there is a Moore’s law of renewable energy taking place, where solar panel prices drop about 10 percent for every doubling of global installed capacity. The long-term trend is clear: solar prices are falling and will keep on falling as we install more and more megawatts.

Wind power price declines have not been as consistent, with the lowest prices achieved in 2003 in the U.S., then rising far higher and since coming down again. A complicating factor for wind turbines is that their efficiency has improved considerably in recent years, allowing for higher prices per watt but declining prices per watt-hour (due to the increased efficiency). See Figure 2 for the long-term trends for wind and solar.

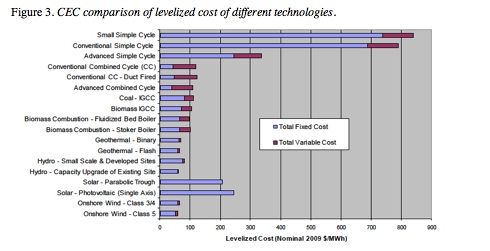

The California Energy Commission also issues a report every couple of years that compares the levelized cost of energy across different technologies. The levelized cost is the average cost of power produced over the expected lifetime of the facility, allowing an apples-to-apples comparison across technologies. The most recent report from early 2010 shows that all renewables except solar are as cheap or cheaper than natural gas power plants. Since 2010, natural gas costs and solar costs have dropped substantially (as Figure 1 shows, they’ve dropped by half since 2010), but the gap has closed remarkably for solar power in general, such that many contracts like the BrightSource contract are in fact coming in below the cost of power from a new natural gas power plant, which are referred to as either “simple cycle” or “combined cycle” plants in the chart below.

Summing up

Clearly, establishing what is “cost-effective” or not when it comes to renewables is not a simple matter. However, what is simple and clear is this: fossil fuel prices in the long term are only going up. And renewable energy prices are only going down. It is that simple. And as more farsighted jurisdictions like California, Germany, Portugal, etc. promote renewables with wise policy decisions, they help enhance the existing, very favorable pricing trends for renewables. Germany’s long-term feed-in tariff is almost singlehandedly responsible for the dramatic price declines in solar power because it brought the global solar power market to scale.

What California began in the 1980s, when the state enacted its own feed-in tariff under the federal PURPA law, Germany improved and expanded upon. California is now starting to regain its leadership in this space, after being in the doldrums for about twenty years.

Renewable energy projects face many hurdles in today’s market in California and elsewhere, including:

- Hideously complex and expensive interconnection procedures

- Very limited number of available power purchase agreements

- An opaque incentive environment due to legislative uncertainty

- Challenging permitting procedures, particularly in states like California that have a history of extremely rigorous permitting standards

If we are serious about tackling threats like climate change and peak oil, we’ll need to do everything we can to continue the remarkable growth in renewable energy and energy efficiency for another decade or two. We’ve got a lot of work still left to do.

***

Tam Hunt is an attorney specializing in renewable energy law. He owns the consulting firm Community Renewable Solutions LLC, based in Santa Barbara, California.