Could twisting the knob on your refrigerated warehouse help the grid balance itself in a crisis? Or could a big water utility help match the ups and downs of the region’s wind power, simply by shifting how fast it pumps water, and when?

These aren’t academic questions for Enbala Power Networks. The Toronto-based startup has been hooking up water utilities, cold storage facilities and other such power users to mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM since late 2011, in a program that taps building-side loads in as little as four seconds to help keep grid frequency within safe margins. That’s a lot faster than the traditional form of demand response that PJM helped pioneer in the United States, and thus a lot more lucrative.

Enbala is also working on a project in New Brunswick, where it’s managing commercial and industrial sites to match their variable power loads to the province’s growing share of intermittent wind power. In December, it was named one of three demand response technologies chosen by Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO), alongside flywheel and battery-backed storage projects aimed at balancing the province’s growing share of wind and solar power as it seeks to go coal-free by year’s end.

CEO Ron Dizy describes big power users like his customers as untapped resources of energy storage, or more precisely, energy flexibility. Water utilities have flexibility in how quickly they need to move water around the system, for example, and cold storage facilities have some leeway in how long they can reduce or cut the power before things begin to thaw.

That’s not the same thing as energy waste, which can be captured through efficiency -- though Enbala’s system can also help customers fine-tune their power consumption patterns and the like. Instead, it’s a finite resource that lurks within a customer’s day-to-day operations, lasting from seconds to around an hour and a half or so, depending on each customer’s limitations, he said -- and that makes it a source of grid-scale power adjustment that’s already bought and paid for, just sitting there waiting to be used.

“Most system operators are saying they need flexibility, a real-time way to balance the power supply,” he said in a Friday interview. “Instead of buying new flexibility, why don’t we enable the flexibility we already have? There’s storage already in the power system, in the form of that reservoir pumping station, that cold storage facility, the aeration plant of a sewer -- it’s all storage.”

Enbala can connect to a typical industrial control system at a cost of about $100 a kilowatt, in terms of the flexibility it can enable within a customer’s operational and economic limits, Dizy said. That’s a pretty favorable comparison to the prices utilities are paying for grid-scale battery storage today, which are many times more expensive -- though batteries can be cost-effective in certain situations where load balancing isn't suitable, he noted.

Enbala then runs its customers’ systems from its network operations center, acting like a generator would to bid and provide its regulation services to customers like PJM and IESO, he said. The company has also licensed its technology to at least one utility that’s running it on its own, he said, though he wouldn’t name the customer.

How much of this untapped flexibility is out there in the world’s industrial and utility networks? Dizy said that a study conducted by Enbala and the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) found about 26 gigawatts, or about 3 percent of the U.S.’s total power consumption.

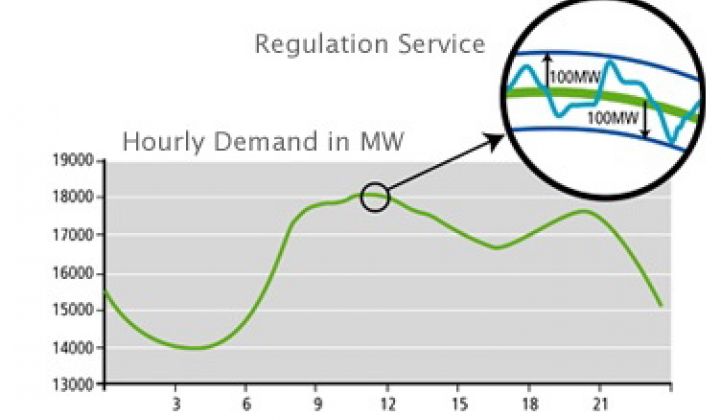

Dizy didn’t disclose how much load Enbala is managing at present, though the IESO project has set aside 10 megawatts of regulation from alternative sources like real-time demand response, to give a sense of the relatively small scales at which demand response is being incorporated into broader frequency regulation markets. But the U.S. uses between 1 percent and 1.5 percent of its overall generation just for frequency regulation, to give a sense of the scale of the potential market for a building-side, load-balancing approach.

Enbala is far from the only one trying to match fast-acting building power controls to meet emerging grid markets. Demand response aggregator EnerNOC is doing frequency regulation for Alberta’s grid operator, though it hasn’t yet jumped into providing the same fast services in PJM, which remains its biggest market for traditional demand response. Big companies like Schneider Electric, Siemens, General Electric and Johnson Controls have built, and bought, their way into more sophisticated building-to-grid controls.

One startup with a similar approach to melding smart buildings and smart energy markets is Philadelphia-based Viridity Energy, which joined Enbala in becoming the first providers of demand-side frequency regulation back in late 2011. Viridity is also managing similar projects (like capturing braking power for its hometown train system, SEPTA) that rely on fast response times. Others with technology that link buildings to grids include BuildingIQ, an HVAC optimization startup with Schneider and Siemens as investment partners; Blue Pillar, a specialist in power management for hospitals and other backup-generator-equipped clients; and Powerit Solutions, which specializes in power sensor and control networks for industrial customers.

As for balancing wind power, we’ve seen projects from Honeywell, which is doing OpenADR-based building-to-grid balancing projects in Hawaii, the U.K. and China; EnerNOC, which is working with partners in a DOE-stimulus-grant-backed wind balancing project in the Pacific Northwest; and big battery-based energy storage projects from the likes of AES, A123, Xtreme Power and others backing up wind farms. Dizy said that Enbala was looking at Texas as another market ripe for wind power integration.

Enbala was founded in 2003 as Sempa Power, a hybrid heating system maker, but shifted to its current focus in 2009, two years after Dizy came on. It raised $8 million in 2010 (PDF) from investors including EnerTech Capital, Chrysalix Energy Venture Capital, Export Development Canada, the Walsingham Fund and XPV Capital. The company also closed on $7.4 million of a still-open investment round in January, according to VentureWire (PDF), and was awarded a $1.8 million grant from Ontario’s Energy Ministry in June, to bring total funding to just more than $16 million.