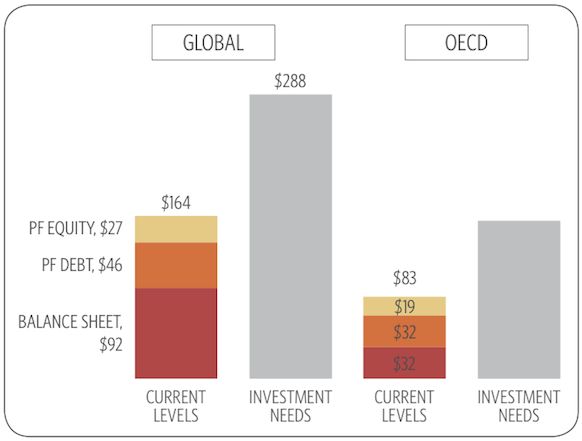

Solar and wind energy require a lot of upfront capital, but provide steady, predictable returns over 25-year-plus project lifetimes. These are the kind of assets in demand by often-conservative institutional investors.

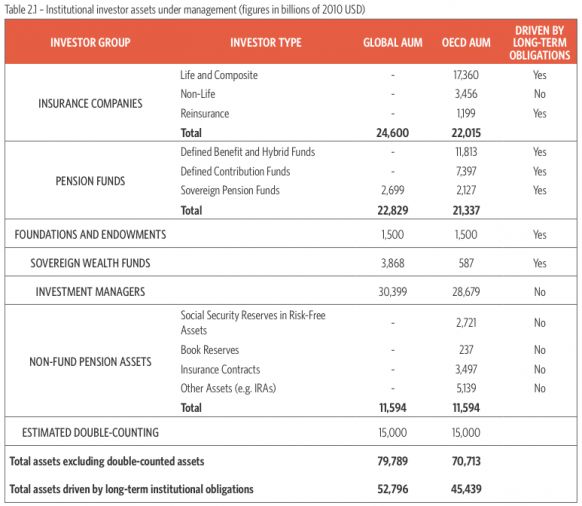

Managers of pension, insurance, sovereign wealth and endowment funds control an estimated $71 trillion in potential investments in search of low-risk, modest-return opportunities.

Institutional capital, one of the world’s biggest pools of private money, could benefit renewables and the funds. “Institutions could enhance their own risk-adjusted returns,” reported the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) in the report The Challenge of Institutional Investment in Renewable Energy, as well as “lower[ing] the cost of financing renewable energy.”

The wind industry’s $0.022 per kilowatt-hour production tax credit (PTC) was recently extended after the industry announced it was ready to consider phasing it out by 2018. The solar industry is preparing to face the reduction of its 30 percent investment tax credit (ITC) to 10 percent after 2016, and probably to zero thereafter. Ample low-cost capital willing to await a slow steady return could be better for solar and wind than the incentives.

Money is available, CPI said, but the renewables’ high upfront costs and slow rates of return do not appeal to the governments and energy consumers that have been asked to provide it. Institutional investors, because of their “distinctive risk/return requirements and longer-term objectives,” could be attracted to renewables.

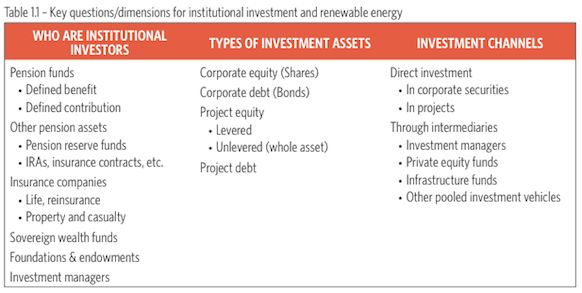

CPI compared the investors’ objectives with renewable energy investment needs. “Differences between pension funds and insurance companies, large companies and small, and a host of other distinctions, determine what is possible,” CPI found. Furthermore, “differences between debt markets and equity markets, direct investments, investment through project or infrastructure funds, or investment through stocks and bonds all have a profound effect on the potential impact of institutional investors,” according to the report.

Of the three ways institutional money could go to renewables, CPI found:

- Investment in corporations with renewables in their portfolio is the simplest solution, but would not likely change those corporations’ overall strategies;

- Direct investment in projects requires expertise and would therefore only be practical for the 150 largest institutions; and

- Investment vehicles and funds can be designed to suit various investment preferences and to meet the liquidity needs of smaller institutions with less than $50 billion under management, but only buy-and-hold-to-maturity offerings would suit the long-term needs of renewables projects, and that would compromise the liquidity of the investments.

Source: Climate Policy Initiative

Direct investing seems to have the most potential. “The largest 150 or so institutional investors have the biggest opportunity to affect the cost of financing renewable energy by directly investing in project equity or debt,” CPI concluded. “Pension funds have greater potential for investment in project equity, while life insurance companies’ potential is more focused on project debt.”

But institutional investors “are unlikely to become the dominant source of project finance,” CPI said, because of barriers involving energy policy, financial regulation, and institutional investment practices.

Source: Climate Policy Initiative

There are three types of policy barriers. Some policies can encourage renewable energy but discourage institutional investors. Tax credits are useless to tax-exempt pension funds. Some can impede institutional investors. European energy market safeguards force utilities to choose between renewable energy generation and their transmission assets. And mitigated or inconsistent policies like Spain’s retroactive tariff cuts and start-stop U.S. tax credits increase investors’ perceived risk.

“The primary objective of institutional investors is to provide services such as pensions and life insurance at reasonable costs, with a very high degree of certainty,” according to the report. “These investors must maintain appropriate levels of liquidity, transparency, diversification, and risk to maintain this certainty.” Regulatory codes formalize the investors’ requirements but, the report added, regulations can be designed to support institutions’ participation in renewables development.

Very few institutional investors, the report noted, have caught up with the opportunities available in renewable energy.

CPI recommended five fixes:

- Eliminate policy barriers;

- Improve institutional investors’ tolerance for illiquidity and create institutional teams that understand renewables;

- Modify regulatory constraints without compromising the institutions;

- Design diversified funds and vehicles with liquidity and low transaction costs linked to renewable energy projects; and

- Encourage utilities and other corporate investors.

“Institutional investors alone will not solve the challenge of renewable energy investment, and scaling up investment from institutional investors will be a difficult task,” CPI concluded, adding that the “the prize is substantial.”

Source: Climate Policy Institute