The coming reduction of the 30 percent federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) for solar creates a steep cliff no matter which way you crunch the numbers, according to a new policy paper from George Washington University. But there are ways to soften the blow.

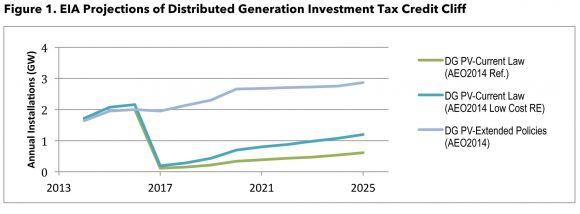

With the phase-down of the tax credit, the U.S. Energy Information Administration projects a 94 percent decrease in distributed solar PV installations from 2016 to 2017, with 2025 levels still below 2016 levels. (EIA estimates are often notoriously low, however.)

“The ITC cliff not only decreases deployment sharply, but it also delays cost reductions associated with increased deployment that could mitigate the impact of the ITC expiration,” James Mueller and Amit Ronen of George Washington University’s Solar Institute explain in the white paper.

The picture for utility-scale solar PV is not much better, with an approximately 80 percent decrease in installations from 2016 to 2017. The GW Solar Institute’s figures are less dire, but still significant: a 42 percent drop in utility installations and 15 percent fewer distributed solar PV installations.

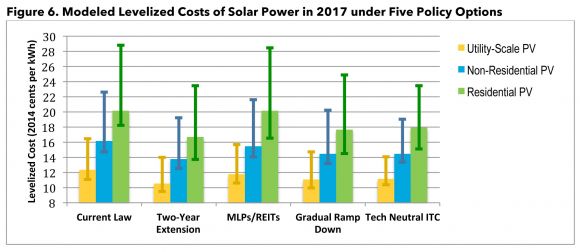

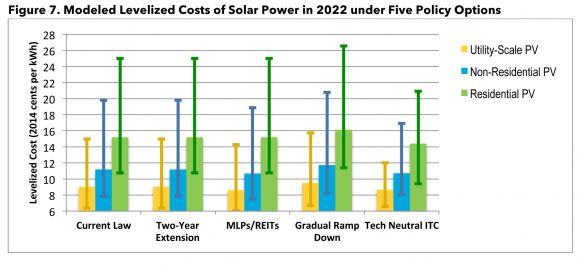

Overall, the levelized cost of energy from solar power will increase by at least 10 percent from 2016 to 2017, the researchers found. “While such an increase may seem insignificant relative to the recent reductions in solar installation costs, the price spike coincides with saturating renewable energy markets in the leading solar states and minimal new incentives in lagging states,” they explain in the paper.

The researchers outlined four alternatives that could soften the landing, but not erode the solar tax cliff altogether.

Two-year extension. A straightforward extension, along with a modification to include projects that have begun construction, rather than those that have gone into service, could “greatly help” during a critical period of extension, but would not provide the market certainty of the 2008 extension.

Forget the ITC. Another alternative for Congress to consider is to allow clean energy projects to use financing structures such as master limited partnerships (MLPs) and real estate investment trusts (REITs) with the five-year modified accelerated cost recovery system still in place. No matter what happens with the ITC, the researchers urge Congress to maintain accelerated depreciation, which they found more than pays for itself in revenues from induced economic growth in the long term. Besides REITs and MLPs, others have suggested that solar could also be included in mortgages.

Gradual ramp-down. Instead of dropping the ITC, Congress could gradually reduce it by 5 percent each year until it reaches zero in 2022. In this scenario, the permanent 10 percent ITC for commercial projects would be eliminated.

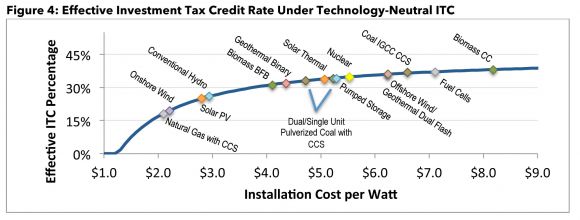

Technology-neutral ITC. Looking beyond just solar, GW researchers see a role for the ITC to be expanded to other energy technologies.

A technology-neural ITC could be automatically phased out based on market maturity, instead of Congress having to determine what maturity looks like. There would also be a cap on the ITC for any technology at 30 percent. For solar, market maturity and scale would be defined by the U.S. Department of Energy’s SunShot goals.

The policy paper ultimately recommends a combination of the four approaches, with a short-term extension and gradual phase-out as the most important.

"Given the extreme sensitivity to the ITC level in 2017, practical lag times for businesses to adapt to new policies, and uncertain cost reductions, extending the 30-percent level for a couple of years would be the most prudent path in the short term to protect taxpayer dollars already invested in commercializing solar and bringing it to full scale,” the researchers conclude. “The cost of this increased support in the near term could be recovered over the long term by ending the permanent 10 percent ITC level in later years.”

Listen to a recent Energy Gang episode for a debate on whether the solar industry needs the ITC after 2016: